Jules Feiffer, from <a href="www.randomhouse.com/catalog/display.pperl?isbn=9780385531580">Backing Into Forward</a>

In his new memoir, Backing Into Forward, Jules Feiffer describes channeling dyslexia, anxiety, and a troubled childhood into a prolific career. “There’s some brain damage,” he jokes, “but I’ve never met a cartoonist who isn’t quirky or weird in some ways.” Fortunately, the Oscar-, Pulitzer-, Obie-, and Polk-winning author and illustrator’s quirks remain in full bloom. The 81-year-old is still cranking out political cartoons and working on kids’ books with his daughter and—after a 50-year hiatus—The Phantom Tollbooth author Norton Juster (their new book, The Odius Ogre, was released in September). Not that he’s gone soft; his satire remains as sharp as ever: “The grown-ups, or the ones I choose to go after, deserve everything they get.”

Mother Jones: I should start by confessing that I named my son after Milo in The Phantom Tollbooth and, like a lot of people, became familiar with you through your children’s books. How does it feel to have that be the way into people’s hearts—the softer side of Jules?

Jules Feiffer: [Laughs.] As long as they pay attention, why should I care? I love doing the children’s books as much as anything else I’ve done. As a matter of fact, just coming back from the audiologist because the hearing aids I’ve just spent $7,000 on weren’t worth a goddam thing, I wrote new picture book on the bus just to cheer myself up.

MJ: Do the kids’ books feel like they’re on a continuum to the very dark social satire that you’ve done?

JF: No, no. It’s a different part of me. Until kids’ books, I was never able to show the more playful side, the sillier side, and just be out-and-out goofy.

MJ: In your book, you say that the best cartoons or comics are when one person does all the writing and the drawing. I found it interesting in context of The Phantom Tollbooth, because I can’t imagine a better pairing of text and image.

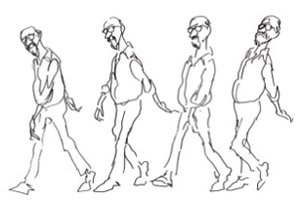

JF: Well Norton [Juster] and I have for the first time in 50 years just done another book, which is coming out in the fall. It’s a picture book for younger kids, called The Odious Ogre, which will be in color. What I’ve tried to do is kind of get inside the author’s head and do a presentation that he or she might want to do if they could draw. It’s all about telling the story, and telling the story from the inside. What I’ve always done with the cartoons, in terms of my art, is try to get inside the characters I’m talking about. You know, the character who is speaking, is showing us through body language and through facial expression what he or she is thinking, what the struggle is that’s going on, and visualize it as much as verbalize it, and that’s what I try to do in the kids’ books.

MJ: Your kids’ books do such a wonderful job of capturing loneliness and other emotional states that we think of, falsely, as adult concepts.

JF: I couldn’t actually write kids books and go on the attack the way I do with grownups. The grownups, or the ones I choose to go after, deserve everything they get. But kids are in ongoing need of support, and they get various versions of it from grownups which aren’t legitimate—a grownup’s version of what we think you should have. We tell you what creativity is, and we even tell you what you’re thinking. What I try to get at in my books is akin to that sense that Holden Caulfield felt when he reads a writer and wants to call him up in the middle of the night—to be a friend to the reader.

MJ: If you were a kid today, do you think you’d be drawn to comics, or would you be blogging or writing for The Onion?

JF: In the Depression, besides everybody being poor, our entertainment was much more primitive and innocent. The comic strip, which I so venerated, was still a very new form. Movies had just become talkies. Radio had just gone coast to coast for the first time. Network radio had just begun when I was a kid. So all of these forms were more or less in their infancy, and feeling their oats. Comics were fresh and funny and nervy, and in a sense, defiant of the prevailing culture. The rebellion was not in terms of anarchy or Bolshevism—but in having a good time in spite of it all and laughing in your face. Ginger Rogers sang “We’re in the Money” and “Gold Diggers” in 1933 when nobody had any money.

I don’t know if the form would be as attractive to me starting today. I’m not electronically geared at all; I’m really a 19th century cartoonist. I have a 15-year-old daughter, and what she’s attracted to is of course iPod and this pod and that, I mean stuff I don’t even begin to know—I never learned how to type for Christ’s sake! I can’t get in her head and find out what she would do if she had the kind of talent I had, I don’t have a clue. Every generation comes up with its own quirkiness and its own culture which gets its inspiration from what’s in the air at that time.

MJ: You’ve worked many different forms, but I’m wondering, what can a static image or panel do that a play or an animated form can’t do as well?

JF: Well, I think a play can do almost anything, because it’s also a static form, much more so than in a movie. In a movie you can move the scenery, you can do anything any way. A cartoon, happens in a limited amount of space and a limited amount of time, and you can only get so many words before the reader’s gonna get impatient. All of these forms that I enjoy are in a sense a slight of hand, where you have to suggest much more than you really show. You have to, in a sense, seduce the reader and trick the reader or the audience into going with you. When I write a play, my whole intent at bottom is to get the audience to be in the cast, to get that audience on stage with the actors and to get them thoroughly involved in what’s going on.

MJ: Many of your Village Voice cartoons mocked the Man in the Gray Flannel Suit type, the conformist.

JF: Mockery was never what I thought it was doing. I came to maturity, or lack of it, during the Cold War, and there were all sorts of pernicious influences that simply were not being commented on. I wasn’t mocking them because you mock things that people know about. I was just simply exposing it. Later on people said, “How’d you get that into print?” because, as I say in the book, liberals didn’t know they had First Amendment rights.

MJ: Do you think that your treatment by the Village Voice, which fired you in 1997 after 42 years, was a particular incident or an indicator of what’s happening to journalism more broadly?

JF: What made it so egregious and noticeable was simply my long history with the paper and their cavalier contempt for that. It was a blessing in disguise, because they could have, with any kind of settlement, ended my cartoon career; I would’ve had nothing to complain about and would’ve been forgotten. They were schmucks. I find that in general, the right and conservatives deal with their artists better than the left; part of them think they’re doing a favor by publishing you. It’s all for a good cause, so why do you want to get paid for it? With all of the changes back and forth on the left, there’s still much more of a loyalty to one’s own group’s beliefs than there is to any degree of effectiveness. That’s why Obama’s throwing so many people on the left into a rage. But I’m not one of them.

MJ: No?

JF: No. I think he’s great.

MJ: I was wondering about that because at the end of your memoir you have sort of a love letter to him.

JF: Yes. He’s not doing half the things that I would like him to do, but the half that he is doing is certainly more than we’ve gotten in many, many years and more than we would have gotten from anybody else that we could think of. And certainly more than Hillary would have been able to do or wanted to do. There were certain things that he said he would do that he hasn’t gotten around to yet. And I’m sure there’s other things he’s going to reverse. And I’m not happy with the Afghanistan commitment at all. But in general, I think he’s been remarkable considering the nature of the opposition against him and the money and the power they have. I mean, he’s the smartest guy in his office in probably close to a century, so let’s hope that includes learning on the job. So far that evidence is not overwhelming, but we have to have hope.

MJ: Your mom comes in for some pretty rough criticism in your book.

JF: There are people who give you nothing but bad advice, and unfortunately one of them was my mother.

MJ: She was an artist; that must have had an influence on you, too.

JF: Oh, no question that the talent, the urge to draw, came from her. But because she complained how little pleasure she got out of it and how she suffered—over the years I learned to distrust writers who talked about how they squeezed the blood onto the typewriter. They just don’t want you to know how much fun they have—you’ll resent it.

MJ: Do you think that’s true?

JF: No. [Laughs.] I don’t want to do it if it’s not fun. I don’t mean that I giggle all the way through; I spent five years on this memoir, and it must’ve been revised seven times. That was hard work, but I had a ball.

MJ: Do you think that having had a troubling parental experience is helpful for writing good children’s characters?

JF: I think we overrate experience and what we’ve been through in terms of our success at doing the work we do. There are many people who get beat up, who suffer, who are victimized, and then they sit down to write and they write crap. How many of these graphic novels over the years are from really talented people? Most of them actually, if you look at them, are self-pitying confessionals about “poor me.”

MJ: Do you think if you were in school today you would have been diagnosed as dyslexic?

JF: I’ve thought about that endless numbers of times. I’m well beyond dyslexic: I have no sense of direction; I never know where I am. When I back up a car, I’m more likely to hit what’s behind me than not, because I have no vision for it. I’ve never been able to play games or play cards because I can’t in my head get the next move. I’ve never been able to balance a checkbook. So there’s some brain damage, but it may be that very brain damage that allows me to do the work I do. I’ve never met a cartoonist who isn’t quirky or weird in some ways.