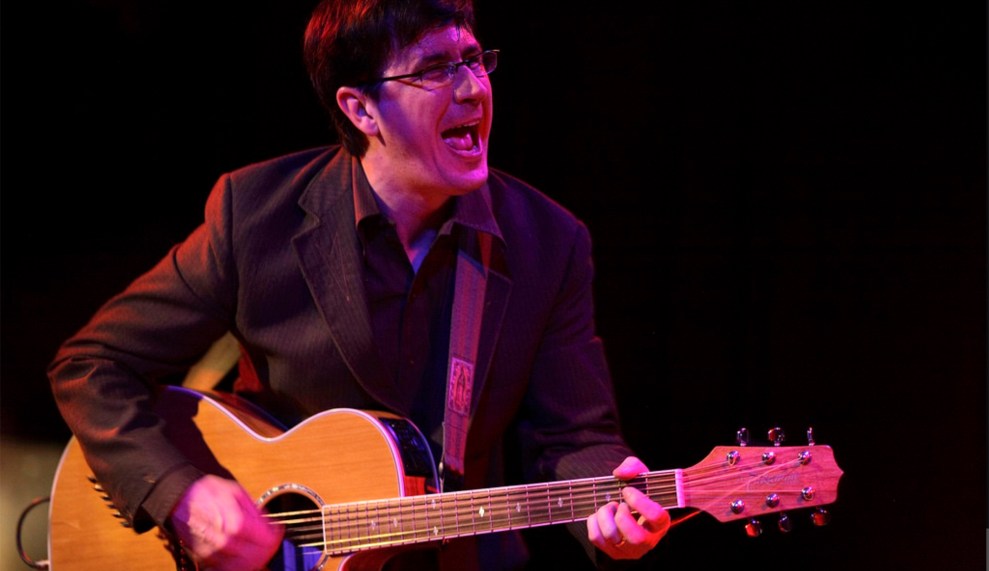

<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/righton/">Laura Musselman/Flickr</a>

When news of the forthcoming Mountain Goats record hit the internet this past December, obsessive fans—which is to say, most Mountain Goats fans—flew into a re-tweeting frenzy. All Eternals Deck, out March 29 on Merge, is the North Carolina-based indie group’s 13th studio album, yet front man John Darnielle—immortalized in 2005 by New Yorker pop critic Sasha Frere-Jones as “America’s best non-hip-hop lyricist”—still enjoys cult-favorite status. His delivery can be raw, and his bittersweet, often confessional, odes to adolescence, religion, and divorce aren’t for everyone. But those who love his work hold it very dear: In 2009, when the group made its national TV debut on The Colbert Report, a friend of mine said it made him feel both sad and proud—like watching your little brother leave for college.

Named for “an apocryphal tarot deck” that captured Darnielle’s imagination, the new album deals in the occult, with visions of deserted towns, dusty Trans Ams, and vampires layered over string arrangements and slide guitar. Besides Darnielle, who plays guitar, the Mountain Goats include bassist Peter Hughes and drummer Jon Wurster—with renowned heavy-metal producer Erik Rutan adding polish and weight to a handful of the new songs.

While Darnielle’s songwriting often feels like straight autobiography, there are personal passions he leaves out of the music, namely politics. Darnielle grew up with Mother Jones on his parents’ coffee table, so I figured he’d want to talk about things like animal rights—which he did. But what really has him fired up is the GOP’s escalating assault on abortion rights (see page 2). The loquacious lyricist also gave me the lowdown on his love for horror flicks, the moment that made him a vegetarian, and that guy who won’t shut up in your women’s studies class.

Mother Jones: What’s it like to be done with the new record but not have it out yet?

John Darnielle: I call it the bottleneck—and that’s a longer and longer process. I think taking too long to work on a record you sort of lose some of the feeling, so I write as fast as I can; it’s just this manic phase where I’m by myself and or on tour and I write and I write. And I send them to the guys, and we start planning our studio ventures. There’s this ’70s notion of going into the studio and you check in and you make the record and when you emerge you have this statement of where you are artistically. And really, we don’t even live like that anymore. We go in for three days at a time, and we work like animals for those days, and after those visits you see what you did and stitch them together. Finally, at the end of what I think took almost eight or nine months this time, you have this thing, and you do the hard process of throwing out the songs that you don’t think belong so you can get the leanest set of competitors.

And then you go into the bottleneck. It makes me envious of anybody who can say truly that they don’t care what anybody thinks of what they do, because I care a lot about the people who like my stuff. But at the same time, as an artist, you always have to be growing. You don’t just want to do what you already know people like—or I don’t, anyway. In the case of this record, we’re incredibly proud of it. I’m very eager for people to hear it. I kind of can’t wait until it leaks. Back in the day, you could give people tapes, but you can’t do that anymore, because it would be available to everyone on the planet within an hour.

MJ: “The people who like your stuff” seems like a pretty distinct group of people—is that whom you’re writing for?

JD: Well, no. I would be doing it if there were nobody listening. But I do think a lot about how it’s sort of a shared journey. I’m finding things out about myself as a person—as a writer—as I write, and so are the people who listen to what I do. But they have this additional aspect of how they take the stuff that I do, and so it broadens the work and it creates this strange connection. It’s really a way of strangers communicating through this third thing, which is a body of work. But really, I know it’s a cliché to say I write for myself, but I write for myself. Sometimes we split the [listeners]: When we finished making Get Lonely, we felt strongly that we had done something special. Some people didn’t want to come along that way—it was so down and slow and quiet; everything’s just this dark autumn day for 35 or 38 minutes. But then there are others who really responded. I’m proud of the fact that we followed our vision there.

MJ: One thing you’re known for is being incredibly prolific; All Eternals Deck will be your eighth album in as many years. How do you maintain that pace? And do you have any advice for would-be writers?

JD: I think it’s mostly that I am a person of high energy. [Laughs.] That, and I sit down and I write when I get an idea—I put other things aside. Most of All Hail West Texas was written during orientation at a new job I had. I had basically worked this job before, I knew this stuff, so I was writing lyrics in the margins of all the Xeroxed material. I would go home at 3 o’clock, and my wife was out of town up at hockey camp in Vance, and I would sit down and bang out a song and then make dinner. Part of it is recognizing that while writing is a mystical process, it’s also work. If you show up to work five days in a row, nobody’s going to pat you on the back—everyone does that. Well, do that with your writing. Just show up. Be there for it. When you get an idea, write it down somewhere and then be a steward of that idea.

When I was kid, they always used to tell me to keep notebooks. I look at my shelves now and it’s just nothing but notebooks. And if I haven’t gotten an idea but I have time to work, I’ll pull one out and I bet there will be five or six sentences that will kick me off. This whole album, all the titles came from that—I just started writing down phrases I’d hear with three words because they looked so orderly on a page. And then I would look at them after six months and be like, oh, Outer Scorpion Squadron, wow, what is that? What’s that mean? What does that conjure up? At some point of distance it becomes like you’re taking inspiration from elsewhere, which is a nice feeling: Instead of making the demand on yourself that you be inspired right now, you have this phrase that’s a little distant from you.

MJ: Can you touch on the new record’s horror-movie influences?

JD: I go to Retrofantasma, a monthly film series at the Carolina Theatre [in Durham, N.C.]. What I like is horror movies, including ’80s slasher movies that politically I have all kinds of problems with. Which is an interesting balance, because I have this leftist puritan strain that, well, if you like something that goes against your politics, maybe you should train yourself not to like it. But I know that I like horror movies and that’s what I watch when I get a moment. So, I went to Burnt Offerings, which is this remarkable film because it’s almost all tone until the last 10 minutes. Very little happens, long stretches of nothing, and then this burst of disorder and chaos that’s really magnificently done. I sort of wanted to capture that multiple-grayscale feel of a lot of ’70s stuff, where there’s this big textural gesture toward establishing all this color underneath, so when there’s some action it just seems to arise from nowhere. I think Go Ask Alice is the same way, where it asks you to believe all these ridiculous things—but if you were in junior high reading it, and believing it, it just sounds like the world is full of these mystical and terrifying detours.

MJ: In one interview, you mentioned that All Eternals Deck has a general undercurrent of dread. Something about the way you said that made me think of the Rob Zombie movie, House of 1000 Corpses.

JD: Oh yeah, that one’s good! Have you seen Red Devil? Again, there’s not a whole lot that happens in it, but there are these reveal moments of like, suddenly you see this hallway that someone’s walking down, and on the other side of the wall is just this scene of relentless carnage. So that’s what I want! Except that I’m me, and if I’m singing about a room where there are bodies on the floor and nobody knows where they came from and something bad is about to happen, the one living person in that room is going to find something to feel good about. And that’s kind of what I do.

MJ: You seem interested in narrative, so I’m wondering how you pick the order of your songs, and also whether, in this age of “shuffle,” it bothers you to be sandwiched between, say, Katy Perry and Insane Clown Posse?

JD: [Laughs.] No! If my songs are being listened to between any other songs, that is awesome, and I’m glad people are getting something out of them. We go to countries like Germany, where I can’t imagine that all of my fans are engaging with the lyrics first and foremost. I think they’re catching a vibe, a feeling. I consider myself a lyricist first and foremost, but if you get something else out of what I do, that’s fine too. I’m not sitting back here telling people how they have to take my stuff. We just want to play music, and hope that people like it.

As far as sequencing, I try to make an album that hangs together as a beginning-to-end piece that, at least once before you pick out your favorite songs, you’ll be able to sit back and have a quasi-cinematic or novelistic experience. That if you start blank and the first song starts, you catch a mood from that and you follow that mood to the end of the last song. We’ve done this a couple of times—me and Peter take a special pride in it—where the second-to-last song drops you off in a certain place, and then the last song kind of does a “glass of water after you’ve emerged from the steam room” thing. I really love that that “Liza Forever Minelli” is the last song. I think it’s one of my best vocal performances ever, with all of us live in a room, no overdubbing. When I sit down to listen to the album, I don’t necessarily listen to it all the way through. I go to “Age of Kings,” or “The Autopsy Garland,” because I just really like the evil vibe of that one.

MJ: You mentioned via email that part of the reason you wanted to talk to us was because of what’s happening in Congress with abortion right now. Care to elaborate?

JD: I was wondering if we were going talk about that, because I get really emotional about this stuff. My stepfather was also really active in the left; I learned to be compassionate about the struggle of disenfranchised people from him. I tried to put some of the tenderness of things we went through on the last song of Sunset Tree, but it’s only the last song of that album. And the thing is, when a person teaches you those values and also abuses your family, it’s a hard thing. It’s weird, and it’s hard to explain, in song or elsewhere. The best way to explain it is families are extraordinarily complex units, and everyone in a family is probably going to be a hero and a villain at the same time.

But I was definitely raised in the California left, in the Peace and Freedom Party, which was the first Third Party to gain ballot status in California—ever, I think. And it was the kind classic lefty movement where you’d spend hours and hours at the state central committee meeting with active, screaming debate about whether we were going to describe ourselves as a feminist socialist party or a socialist feminist party. [Laughs.] Which, in retrospect, you wonder whether that’s time well spent.

I do have all these values, and I’m always hesitant to be too vocal about them. For one, when one talks about one’s values one always seems to be presenting oneself as a good person. I don’t want to make any claims for my own value as a human being. I really just want to say how things seem—and that is, for reproductive rights in America, it’s an extraordinarily dark day. There’s this new bill on the floor called the No Taxpayer Funding for Abortion Act. I just couldn’t be more outraged if it was the No Taxpayer Funding for Diabetes Checks act, because abortion is a health-care right. This is settled law. Some conservative justice, I think it was Roberts, said “Roe v. Wade is settled law.” Now I don’t love John Roberts, but that was a good and true answer; this debate has been had.

There’s a book called Dispatches From the Abortion Wars, and this book explains what it means when you restrict access, what it means to people who don’t live in New York City or L.A. or San Francisco. And it dispels a lot of the myths about abortion, such as, you know, that people use it as birth control. It’s deeply depressing that most people have the wrong idea about what most abortion is actually about, and why it is a vital health care need. And that it’s settled law, and you can’t go around trying to undo it to cater to your base, to say nothing of the fact that they don’t actually want to overturn Roe v. Wade, they just want to keep promising their base that they’ll do it to get votes and dollars. They wouldn’t overturn it if you gave them the pen right now, because that would take an issue away from them. This is a really deeply cynical thing. Every free democracy in the west encourages reproductive rights, because reproductive rights are important.

The other thing I go off about is the fact that there are going to be Democrats who will vote for this bill, and then, come election time, hard lefties like me are going to be told that we have to support them anyway because it was a strategic vote, etcetera. And I’m something of a moralist. I think you just can’t vote for a thing like that, no matter what it costs you in your other areas of your agenda. I don’t want to hear about how you got more done in education: Great. But you voted to take away someone’s rights, so no support from me.

MJ: How do you figure we got to this point?

JD: For one, abortion is a delicate issue. It’s a very hard thing to talk about. No one wants to get an abortion, nobody looks forward to making a difficult to decision like that. Another myth from the right is that people have frivolous abortions. I know a lot of people who have needed an abortion, and I don’t know a one who was like, “Oh yeah, at 2:00, I have my abortion; at 3:00, I want to play tennis.” It’s not any more fun than any surgically invasive procedure—it’s not something you choose lightly. And we have allowed them to perpetuate some myths, plus they’re really good at framing the dialogue, especially because being against anything is easy: Just demonize it and frame it and boom! Everyone who hears your demonization will probably share a little bit of your feeling. It’s harder to explain what it is you’re for when you say you’re for reproductive rights. But we did start using terms like “reproductive rights” and being careful about using “abortion” because it turns people off, and that’s a mistake. When we are talking about reproductive rights, we are talking about a woman’s right to have an abortion. We ought to own that word instead of trying to table it because it makes people feel uncomfortable.

MJ: And now there’s also been a push to frame abortion restrictions as protecting women from the consequences of their decisions.

JD: Yeah, the right has obtained this almost literary cynicism. That’s not something they care about, but they sure are good at making that claim. It’s like, they became feminists when people were mean to Sarah Palin, but they won’t be feminists to defend Nancy Pelosi against horrifying caricatures of her as a human being. My friend [and investigative editor at The Nation] Esther Kaplan has made the point that, look, nobody here likes Sarah Palin, but it is the case that when she says it’s disgraceful and anti-woman for you to paint me as you do, she’s right! I think an appropriate feminist response to the treatment of Sarah Palin by the media is that there has been a lot of misogyny in it, and it doesn’t make you a supporter of Sarah Palin to say that. People loathe her so much, with good reason, that they aren’t willing to stand up for her as a woman and say “You don’t get to be a sexist just because you don’t like somebody.” It’s absurd. If your values are your values, they extend for all women, even and especially ones whose viewpoints you find loathsome. To me, that’s a great opportunity in the whole Sarah Palin thing to discuss—that feminism is about the right of all women to be taken seriously as human beings, not just the right of “our kind of women” to be taken seriously as human beings.

MJ: I’ve read the articles you link to on your blog, and it strikes me that you’re one of the few male pop-culture figures—if you can be called that—who consistently speaks out about this kind of stuff.

JD: I’m reluctant to be too strident, for a number of reasons. One is that men tend to dominate whatever public discourse they participate in, and another big part of feminism is to let women have their say. Men’s voices can be welcome at the table, but there is a time and a place, and maybe it’s now, for men to make a little less noise, make their needs less known, and listen to the needs of others. Everyone knows the stereotype of the feminist male who’s constantly proclaiming his feminism, and that stereotype doesn’t come from nowhere. You know that guy if you had the one guy in the women’s studies class—or if you were that one guy—who was talking half the time in a class of like 30 people.

maybe it’s now, for men to make a little less noise, make their needs less known, and listen to the needs of others. Everyone knows the stereotype of the feminist male who’s constantly proclaiming his feminism, and that stereotype doesn’t come from nowhere. You know that guy if you had the one guy in the women’s studies class—or if you were that one guy—who was talking half the time in a class of like 30 people.

At the same time, we live in increasingly misogynist times. And that is difficult, because the way we think of progress is that it heads in one direction, and I think that’s what we all came out of the ’70s with, this idea that we were heading for the promised land of egalitarianism and so forth. And it turns out—and a lot of historians could’ve told you this—that’s not how history works: Things do go backwards; things go all sorts of directions.

MJ: You’ve also been vocal on animal rights. How’d you get involved with Farm Sanctuary?

JD: Farm Sanctuary is this awesome thing that was founded by Gene Baur, who rescued a sheep, Dolly, that he found in a slaughterhouse castoff pile. She had been left for dead, but she wasn’t dead, and he took her to a farm in upstate New York where she lived out her term of her natural life. So he worked tirelessly for the rights of farm animals to live decent lives with a view toward eventually fewer people eating animals.

To me, animals are sentient creatures who deserve better than to be tossed under a pile of corpses and left to die. So my wife and I—we’re vegetarians and we’ve always liked cows—got an adoption certificate for a cow from Farm Sanctuary and over the years got more and more involved. The main thing they do is rescue animals from bad situations and give them a place where they can just live their lives. And if you go up there to Watkins Glen, and you see cows that are 20 years old, you realize you’ve never seen a 20-year-old cow. The cows you’re used to seeing are three months old because once they hit a year, they’re dead. Animals have characters just like we do, and when you see these animals who have had a chance to develop that character and to grow, it’s life-transforming.

MJ: How long have you been a vegetarian?

JD: Since January 1996, during the blizzard in New York. It’s a classic conversion story, I went from being the guy who special ordered steaks from Omaha—which I still had in the freezer back home in Chicago—when I happened to see a movie in which somebody shoots a pig in the head. And they shoot wide, and the pig clearly thought they were going to feed him and instead they shot him, and he screams. And I was like, wow, that animal is very much like a lot of dogs I have loved. Something clicked in my mind, and I think I had my last pepperoni pizza that day. I haven’t eaten meat since, except for the occasional accidental meat every now and then—every vegetarian goes through phases where they go from being totally traumatized by that to realizing it’s occasionally going to happen, and it doesn’t mean anything. When you’re touring in a foreign country and you’re at a buffet and you don’t speak the language and you think you’ve figured out what something says and then you realize, oh, that meant chicken. [Laughs]. For me it’s not about purity, it’s about what you intend to do.

MJ: For a person with such clear political passions, you’re not an overtly political lyricist. Why do you keep them so separate?

JD: That’s because, as important as politics are to me, the life and the spirit of people’s emotions are much more important. People live real lives where they love and grieve and feel pain and joy and that is a whole separate sphere. All that political stuff, I believe in it strongly, but not as strongly as I believe that at some point you or someone is going to need a song to sit with and comfort them in a hard time. That’s important to me, and if during that song I’m telling you how to vote, I’m not doing my personal job as a songwriter. Other songwriters may be well-placed to talk to you about politics, but the thing that I share with people is how to go into a place of emotion and really revel in it.