Photo by Robert Stewart

Like the protagonists of their riveting new documentary, California filmmakers Katie Galloway and Kelly Duane de la Vega attended high school together. But it was years later, after striking out on their own and working in various cities and having kids, that they moved home to Berkeley and bumped into one another by chance. “We realized that we both had pursued documentary film and decided to go have a drink, and we had strong creative chemistry and decided to do a project together,” Duane de la Vega says. The project was Better This World, a fast-paced, emotional film that has garnered rave reviews on the festival circuit and is scheduled to air September 6 on the PBS program POV (and will then be available on the POV website through October 6).

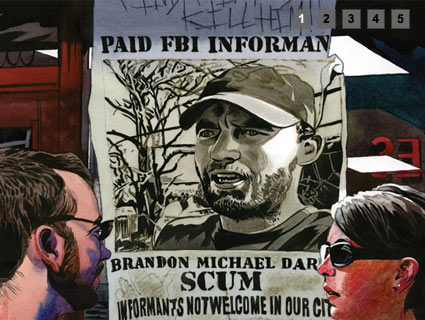

Better This World looks at the cases of Bradley Crowder and David McKay, a pair of fledgling activists who were seized by federal agents at the 2008 Republican National Convention in St. Paul, Minnesota, and charged with making Molotov cocktails, although they never attempted to use them. Their prosecutions hinged on cooperation from Brandon Darby—a well-known activist and cofounder of the radical collective Common Ground—who shocked his colleagues by becoming an undercover snitch for the FBI.

In telling the stories of these three primary characters, the film explores the disturbingly fuzzy line between observing an alleged terrorist plot and encouraging one. It also probes the extent to which the FBI now operates within that gray area and exposes how the system is stacked against defendants who risk trial rather than copping a plea. What ultimately makes the film so powerful is its access and the depth of its character development, which leaves even partially sympathetic viewers with a vivid feeling of: There, but for the grace of God, go I. I caught up with Galloway and Duane de la Vega on the eve of the film’s theatrical debut in New York City. Check out the trailer below, then read the interview.

Mother Jones: How did you guys first hear about the Brandon Darby saga, and what made you decide to dig deeper?

Kelly Duane de la Vega: We first found out about the story in early 2009. There was a piece in the New York Times that talked about this case of a couple of young men from Midland, Texas, who had been charged with domestic terrorism. The fact they were from Midland we thought was interesting; the fact that David McKay was headed into a federal trial and was alleging he’d been entrapped piqued our interest; and we had noticed, as I imagine many of your readers have noticed, that since 9/11 there have been a bunch of cases where there are charges of domestic terrorism and counter-allegations of entrapment by the defense. We thought this would be potentially a great story, because we could sort of look at the case inside out by meeting the people involved and following the trial as it unfolded. So we just jumped on a plane to Minneapolis.

Katie Galloway: Most of my work has been criminal-justice related. I did a film with Ofra Bikel at Frontline called Snitch, about the government’s use of informants in the drug war, and I see a lot of overlap with the war on terror. I also did a film years ago on the anti-globalization protest movement after Seattle. So it was hitting a bunch of different things that have been of interest to me.

MJ: Your access was mind-boggling: FBI and court documents, audio from jailhouse phone calls, tapes of federal interrogations, and great footage, not to mention getting all these FBI guys on camera. How did you do it?

KDV: We got access to David McKay’s lawyer, who helped introduce us to some of the central characters, and he was our first entrée. And then we did a lot of research. You know, we started poring over transcripts, piecing together the puzzle of the story. And once we figured out who the key characters were, we reached out to them and spent time building trust. We knew that these jailhouse phone calls were used as evidence, and so that was something we could potentially get access to. Also Darby’s FBI letter was entered into evidence. And then ultimately, with the FBI, we went in and we got to know them, and we were really lucky that they granted us access.

MJ: Yeah, those guys are usually pretty tight-lipped.

KDV: Lowell Bergman was an early supporter of the film, and he has a strong reputation with the folks at the FBI, and it may be that it came down from somebody he knew that he was involved.

KG: I don’t know about Lowell’s current relationships at the FBI, but he gave us a great piece of advice: that we just get in touch with the local office, the Minneapolis division, and say: “We’re interested in following this case. Can we just come in and meet you and tell you what we’re interested in?” We were very fortunate that when they eventually accepted our offer for coffee, the person who was the public-affairs appointee had moved from McKay and Crowder’s case to public affairs, and so he had intimate knowledge of the case. We kept up with him, and once the case was closed, Minneapolis granted us access. We think it was a confluence of circumstances, good advice, and luck.

MJ: Surveillance was a not-so-subtle theme in the film. What was your intent?

KDV: I think we approached surveillance as a character, almost. One thing is, a series of key events in the film took place when we weren’t present, and so we had to get creative in terms of bringing those moments to life. We discovered that there was a Homeland Security grant given to the Twin Cities for $1.2 million for cameras, and so we knew that so much of the Twin Cities was being taped—everybody coming and going. We figured out how to get access to that and we started watching a lot of footage; we felt that it was part of the larger story, which is a story of the post-9/11 security apparatus, and sort of the growing “security culture.”

MJ: What do you think motivates Brandon Darby?

KG: We weren’t able to sit him down and ask him that point-blank. We’ve talked to a lot of people, obviously, and I’d say the dominant theory is that he has a hero complex. And he had his moment of incredible heroism after Katrina. But as the dust settled, the organizing principle of Common Ground was anarcho-syndicalist, and not hierarchical, and that is not Brandon Darby’s style. That’s reductionist, but he sort of fell out of favor there for various reasons. And many people, including his ex-girlfriend, have said, “I think he wanted to be the hero again,” and the FBI perhaps provided him an opportunity. He is called [a hero] by several conservative blogs, and Andrew Breitbart has become a close ally. So he still gets to sort of play that role. There is another theory that I certainly wonder about, and many have floated: Was Brandon Darby ever a real activist, or was his trajectory always part of some deep cover?

MJ: Or it could have been as simple as Darby being insecure and always needing affirmation.

KDV: A lot of the people in that world sort of live in conspiracy theories and then [when] they find out that one of their own is an undercover FBI informant, it sort of confirms those “paranoid” feelings, right? David McKay talked about how paranoid everybody was, and he kept saying to them, “Why on earth are you paranoid? We’re just a bunch of stupid kids. The FBI has much better things to do than to worry about us.” And the irony was, they were actually…

KG: Right. We don’t talk about it in the film, but it is interesting to look at Darby’s relationships and how they were formed as made his way through the activist world. Scott Crow, who was one of his main allies and one of the cofounders of Common Ground, was a very well-known and well-respected anarchist activist. And Brandon quickly became tight with him, and quickly became tight with members of the Angola Three, and did a lot of work in New Orleans with Malik Rahim and Robert King Wilkerson, both members of the Black Panther party, and so it is an interesting trajectory.

MJ: Now, Darby did talk to you off camera, right?

KDV: I had a phone relationship with him. He had originally agreed to give an interview, but he wanted to wait until after the McKay trial was over. He ultimately changed his mind.

MJ: You used a voice actor to read Darby’s testimony and FBI notes. How did that come about?

KDV: We knew we wanted his voice in the film and we wanted some way to make him present and so we decided to use archival footage. But we also wanted him commenting on the same events that McKay and Crowder are commenting on, and so we felt that a voice actor would be sort of the best bet.

KG: Fortunately for us, Darby was the media spokesperson for Common Ground, so we were able to license a couple of interviews that we felt really brought him alive as a character in a way that you could see how Brad and David would fall for him—you could feel his charisma. Later on, we don’t have footage of him, and so, to continue the story we counted on court transcripts and letters and testimony. The voice actor, who’s another documentary director, actually, did a terrific job.

MJ: You also reenacted certain scenes. Can you talk about that decision?

KDV: None of our verité scenes was re-created. The only times where things are reenacted is when you have, you know, a talking head reflecting on an event and then sort of impressionistic visuals to kind of give you a feeling for it. You know, a handful of people reflecting back and you sort of see a blurry group of men and a table, or the van ride to Minneapolis with the stylized and impressionistic visions of people in the van.

KG: And we only used reenactments with things that happened prior to when we started shooting in 2009.

MJ: It seems like either you were trailing these guys constantly or you got incredibly lucky with a couple of things.

KDV: We were trailing these guys constantly. [Laughs.] And we got really, really lucky.

KG: The other thing people wonder about is how do people let down their guard that much in front of the camera, but if you think about how their kids are facing seven years or thirty years and they’re trying to make a decision about whether to roll the dice on these crazy odds or go to prison. Once they trusted us, the things they were dealing with were so much more immediate and dramatic than the fact that a camera was there that it wasn’t that difficult to capture the drama. It was kind of like fish in a barrel.

MJ: The film is in part an indictment of Brandon Darby, but in a bigger sense it’s an indictment of the federal justice system. Was that the goal?

KDV: To me the main goal was to make a film that revealed the complexities behind these headlines about domestic terrorists. You rarely get to peel away the layers of the onion and understand what’s going on here and how much gray there is. I wanted to lay out the full story and really allow people to think about their own sense of morality: What is government overreach? What is entrapment? Did these kids go too far? And come away with some things to think about, so the next time you see a domestic-terrorism headline maybe you’ll read a little deeper and wonder what all was involved in it.

MJ: I guess I was specifically referring to how the federal system is weighed against people who opt to go to trial.

KG: This case did give you an opportunity to think about the lengths of sentences in the United States. We don’t say it in our film, but sentences are 5 to 12 times as long for comparable crimes in the US as they are in other western industrialized countries. When we showed the film, for example, at Human Rights Watch Film Festival in New York for a pretty international audience, people were shocked that David could be facing up to 30 years for what some people think of as a thought crime. Darby is a pretty easy villain, so it was important to us to make sure that, for those who do think there is a problem here, that it gets laid at the feet of government rather than Brandon Darby specifically. Because I think David says in our trailer that it’s terrible to be a pawn in somebody else’s game. And in certain respects, I see Darby as a pawn in a much bigger game.

KDV: One thing that we did care a lot about was the sort of collateral damage that happens to the families. It’s not just the individuals that are having to go through these excruciating decisions and facing this monster government and feeling powerless, but it’s also their parents and their siblings.

MJ: When we talked to Darby, he claimed Crowder and McKay were lying about looking to him as a kind of mentor. Darby says he struggled to maintain their respect, and that they thought he was past his prime. Do you think it’s possible that neither side is lying—that both sides fully embrace their own perspective?

KDV: From spending a lot of time hearing Brad and David talk about their complex feelings about Brandon, it’s hard to believe that he didn’t have a pretty powerful impact on them. Even the prosecutor says on tape that there’s no dispute that he was a mentor figure.

MJ: So what feedback have you heard from your various characters?

KG: Brad’s been on the festival circuit with us. He likes the film and feels like it accurately portrays his experience, more or less. Which is of course a huge relief when you go to your premiere. We had ours at South by Southwest, in Austin, and many of our characters were there, and both David’s and Brad’s families came.

MJ: This was the first time they had seen it?

KDV: Except for Brad, whom we gave a private screening.

KG: So anyway, the response was entirely positive, I would say, and cathartic. There were family members who were furious at David and Brad, and they had not been able to hear the full story. When David was incarcerated, as he still is, he couldn’t talk openly about all these things on the phone. And so his sister, for example, who held a lot of sadness and hostility about his actions, felt like she understood the circumstances in a different way. That’s just one example.

KDV: And David showed it in prison. He watched it with 20 other prisoners, and he said that all the prisoners were crying. Even though it was a very unique story to him, there were elements of it that felt familiar to all of them, and that felt very gratifying for us. He really felt like we captured the complexities, and we didn’t shy away from the mistakes that David and Brad made. But we also allowed for enough of the story to come out that people could really experience it in a way that he wished they were able to in trial.

KG: We don’t know if Brandon’s seen it yet. He did send a text to Kelly that said, “Congrats. I don’t agree, but congrats.” We’ve just heard secondhand the FBI and prosecutors’ perspectives, and I’m curious to hear their perspectives.

MJ: Over the closing credits, you have audio of Darby talking to radio host G. Gordon Liddy, and Darby is characterizing the likes of Crowder and McKay in much the same language a federal prosecutor might use. Why did you choose to end on that particular note?

KDV: In the beginning you hear these very provocative local newscasts, and then at the end you hear these very sort of exaggerated of retellings of a story, and I think it’s important to sometimes showcase that so you can feel the difference between a complex story that you just lived through and the way the mainstream media sort of spits it back out at you. And then, it was important to show Brandon Darby’s trajectory and where he ended up.

MJ: Not that it’s a big surprise to see the media parroting the narrative of the authorities.

KDV: I think, each time you see it more blatantly, it hopefully has some sort of larger impact in terms of how the general public thinks about the media it’s getting.