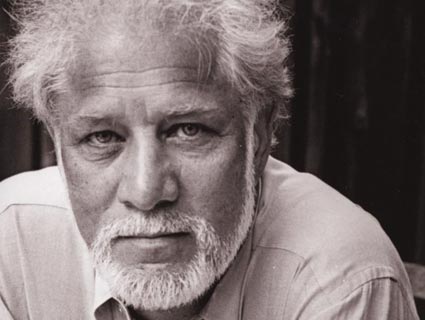

Jeff Nolte/Banff Centre

Born in Sri Lanka and settled in Toronto, author and poet Michael Ondaatje has been messing with genre for the past 40 years. In his 1970 hybrid novel, The Collected Works of Billy the Kid, he layered lyrical poetry, news clippings, photos, and narrative fragments to create a palimpsest of a Wild West hero. Coming Through Slaughter‘s form echoed the improvisational jazz that its protagonist played. And while it is less apparently experimental, it’s hard not to mention The English Patient, the book and later film that launched him into international stardom.

For The Cat’s Table (in bookstores Tuesday), he reimagines his personal history, which would make great fodder for a memoir, but, as he puts it, “What is nonfiction? If a politician writes of his life, and he decides to talk about A rather than X, he’s fictionalizing it. A book is full of omissions.” Instead, Ondaatje offers a lush, imaginative account of three roguish boys wreaking havoc on a ship bound for England, amid a sea of circus performers, thieves, and outcasts.

Mother Jones: I’ve just finished The Cat’s Table. It was more lighthearted than what I’m used to reading from you—very enjoyable.

Michael Ondaatje: It was a pleasure for me to write too. I wrote faster than my usual books. It felt different and looser.

MJ: You’ve called it a novel, but the main character is Michael, and you also moved from Sri Lanka to London as a kid. Can you tell me more about your own voyage?

MO: I kind of was shoveled onto this boat at 11 and went to England. I didn’t have any parent watching over me. It was very free and may have been a bit of a scary time for me, but I really don’t remember much about the voyage apart from playing ping-pong a lot with a couple friends. It really is a novel, because I had to reinvent the world as it might have been.

MJ: Did you get in trouble on the boat?

MO: I’m sure I was in trouble on the boat, but I wasn’t as badly behaved as the three boys on the boat [in The Cat’s Table], I don’t think.

MJ: Did you board a boat to recreate the memory of being on a ship?

MO: I had been on a ship as a kid so I had to re-remember it. It was great to be in a limited space for a book. Whether it’s the villa in The English Patient or a certain location in Sri Lanka for Anil’s Ghost, I often need that limited space. It’s like having a house to roam around in and reinvent and have things to happen in, kind of like a French farce. Doors opening, doors closing, new people arriving, and disappearing, and so forth.

MJ: Speaking of farce, you said in an interview that you’d really like to write a comedy. Scenes in your book are humorous; was that part of your goal?

MO: When I said that to Colum McCann, he looked very appalled. Because I was saying I wish I could write like Noël Coward. I just remember the look on his face as if I had lost my mind. I think I wanted to go back to that kind of joyfulness. People don’t write about kids; you have to give them a lot of freedom, and that causes anarchy and that causes farce.

MJ: Many of your characters are thieves, like Caravaggio in the English patient and several thieves in The Cat’s Table. Did a particular thief make an impression on you in your life?

MO: I’m drawn to them. I think Leonard Cohen has a line about the company of artists is a company of great thieves. There’s a lot of thievery involved in writing. You’re breaking into other people’s spaces and other people’s stories. For that reason thieves are kind of useful and they’re not likable…well, they are likable, but they are not as dangerous as other crimes.

MJ: I have to ask you about Divisadero because I live on Divisadero Street in San Francisco. The title has obvious connections to mirroring and fracturing in your story. Was there anything else on the street that made you name your novel after it?

MO: I was living north of San Francisco in the Petaluma area, which is where part of the book takes place. Whenever I came into town, I would drive under the sign that said Divisadero Street, and I always loved that name. Halfway through the book, I just had to call it something, so I filed it under Divisadero. And it became so metaphorically useful because it was a book in two parts. That was an important street that separated one part of the city from the other. In Spanish, it means looking into a great distance from a height. So all the meanings of “Divisadero” became perfectly apt for the book.

MJ: When I moved to San Francisco, I felt the same attraction to the name of that street.

MO: I haven’t read any of those vampire novels—they take place on Divisadero Street, don’t they? The one with Tom Cruise as a vampire.

MJ: Interview With the Vampire?

MO: Anne Rice. Yeah, I think one of the groups of vampires live on Divisadero Street, so you’d better watch out.

MJ: During your PEN award speech, you said, “I suspect I’m more influenced by other genres than by writing itself.” Recently, what other genres have been inspiring you?

MO: I’ve just seen a film called The Arbor. It’s an English film. It’s an odd film because it’s partially a documentary, but then what they did is they took all the documented interviews and then they gave the actors the parts to lip-sync. So you’re getting a fictional person saying factual words. I’m interested in art forms where things merge.

MJ: People refer to you as an international mongrel. Is that a label you came up with?

MO: There’s a line by William Carlos Williams I mentioned in a speech: “The pure products of America go crazy.” If you go for that kind of purity, you’re going to box yourself in a very small room. We are in a universe where everything around us is mongrel. I come from Sri Lanka; I’ve lived in England; I live in Canada; I go to the States. I’m a complete mixture, as my family background is. We’re in an era, with all the immigration and emigration, surrounded by this great mixture, which is one of the healthiest things we could have. I mean, to have a pure republican belief in something is kind of crazy, and so evasive.

MJ: Reaching way back, I was wondering with The Collected Works of Billy the Kid, how you got so interested in American folklore.

MO: (Laughs.) It’s one of those mongrel things, how we’re influenced by things from far away. When I was a kid growing up in Sri Lanka, suddenly there was this image of Billy the Kid. I remember having a little cowboy outfit as a seven- or eight-year-old. And in the back of Billy the Kid, there’s this little picture of me in this ridiculously decorative cowboy outfit. This bizarre thing, when I was in my early 20s, I kind of came back to that world, looked at all the awful little comic books that were coming out and thought how ridiculously sentimental these books were. So I tried to write a book that was a bit more gritty and realistic about Billy the Kid. But it began with those absurd fantasies of a child.

MJ: As a mongrel, do you think there’s a danger in reaching across to another culture and writing about its folklore?

MO: There was one review, which I loved, which said, why was a Canadian given the rights to edit the journal to Billy the Kid? And I thought, that’s great—they believe it’s all real, so it was a positive critique for me. I was relying on maps and this sort of invention of Billy the Kid.

MJ: You said that you’re not inspired by the writing genre, but you are an editor of Brick. Since the world is a cruel place for novelists who are not yet known, are there any hot new writers we’ve never heard of who you think are exceptional?

MO: In Canada, especially on the East Coast, in Newfoundland, there are some very good writers. Like Michael Winter, who’s a novelist. And poets too. Poetry is such an essential art form, and so few people know what’s happening even in one’s own country. You know, W.S. Merwin, Adrienne Rich, C.D. Wright.

MJ: Were you happy with the way The English Patient was adapted by Hollywood?

MO: I was expecting massive decadence, but it wasn’t. Saul Zaentz, the producer, and [director] Anthony Minghella are actually much more literary than most film people, so it felt like a very private project for them.

MJ: Do you know the American writer Chuck Palahniuk?

MO: Yeah, I know of him.

MJ: His newest book, Damned, is set in a version of hell where in one of the levels, The English Patient plays on a loop. Do you have anything to say to that?

MO: (Laughs.) Oh well, it depends…oh, that’s very funny. I don’t know what to say to that. I’ll have to read the book now, I guess.