Randy Fling

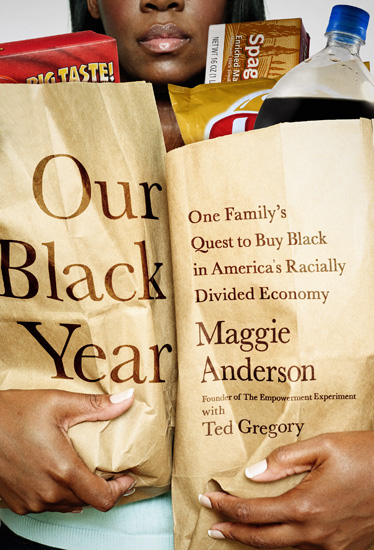

In 2008, Maggie Anderson was doing pretty well. She had a successful career in business consulting, a loving husband and two lovely daughters, a nice house in a trendy Chicago suburb, and attended the same church as the Obamas*. But looking around at her mostly white neighbors, she couldn’t shake the guilty feeling that she’d left the black community behind. A simple solution, she decided, would be to spend more money in the impoverished neighborhoods on Chicago’s West Side. “The whole point,” she said, “was, ‘You know what, we care about the West Side. We need to help those people, those are our people, and we need to do what we can to make a difference there.’ So we thought, instead of buying groceries here in Oak Park we could go buy groceries on the West Side. And it was not that simple at all.”

The problem, Anderson realized, was that most businesses in predominantly black neighborhoods weren’t owned by African Americans; most of the money spent in those concerns would leave the community come closing time. So she persuaded her family to embark on a far more challenging mission: For a full year, they would attempt to spend their cash exclusively at black-owned businesses.

The ensuing adventure, dubbed The Empowerment Experiment and chronicled in Anderson’s book Our Black Year (coauthored by Chicago Tribune reporter Ted Gregory), took them from gritty corner stores at the epicenter of urban decay to Texas megachurches to the boardrooms of the nation’s most powerful trade organizations. By the end, the Andersons emerged from the maw of racial-economic inequality with powerful insights into how black Americans might better wield their collective $913 billion buying power to improve their communities. I spoke with Anderson, whose book comes out this week, about the backlash she encountered, economic segregation in the black community, and the near-impossibility of finding black-made products at Walmart.

Mother Jones: So how have you been shopping since you finished the book?

Maggie Anderson: I like to tell people it’s not like a diet. It’s not like you lose your 20 pounds and then you go out and get a sloppy pizza. So we are totally engrossed in our new lifestyle. For example, just a couple months ago we needed pest control. We were throwing a party here and maybe about three days before I was in the kitchen and saw 10 unidentified flying objects in my kitchen. I spent a good 20 minutes to find a local, black-owned pest control company. And I called and it was a fantastic experience and haven’t seen a bug in the house since. If we ever need something new like that, we do an exhaustive search to at least investigate the possibility of giving that business to an African American entrepreneur. So that’s number one, the little things like that. But it’s not as painstaking as it was during the experiment, [when] every little bit of money we spent, even for last-minute items, had to be black-owned.

MJ: If you had to ballpark it, what would you estimate is the percent of your income spent at black businesses?

MA: I would say a conservative number would be 55 percent.

MJ: What surprised you about the experiment? Courtesy PublicAffairs

Courtesy PublicAffairs

MA: Oh, the worst thing was what we learned about economies in black neighborhoods. We assumed, just like other little ethnic enclaves like Little Italy or Greek Town or Chinatown, that for predominantly black neighborhoods all the black businesses there would be owned by the local people. But easily over 90 percent of the businesses on the West Side—and it’s the same way all over the country—are owned by people who are not black and do not live in that community. So it’s not a “buy local” thing, because these folks set up shop in the black community, sell their wares, make their money, hardly ever employ the local people there—and they put the steel bar over the door, pack up at 6:30, get in their car, drive to their suburb, and take that money with them. And that was the whole reason that these communities suffer the way they do: The everyday exit of the wealth in those neighborhoods directly leads to social crises there.

So I’m literally walking around and talking to people, “Is there a black-owned restaurant, or a black-owned dry cleaner?” and folks are looking at me like I’m insane. And if I didn’t know this, I’m sure that folks outside the black community don’t have this as part of their reality or part of their picture for black America. When we talk about black people, the black situation, problems in the black community, you know, we start with, “Black kids are least likely to graduate from school; black unemployment is four times higher than the national average,” all these numbers. But why can’t we include that over 90 percent of businesses in the black community are not owned by black people or local residents? If we were to add that to the conversation, maybe folks would say, “Oh, well no wonder things are so bad there,” and start thinking about things in a different way instead of allowing those awful numbers to be a reflection of our propensities. Why is it that my people are just supposed to be the perpetual consumer class, and everyone else is supposed to benefit from our money?

MJ: So you had trouble finding black businesses to patronize in black neighborhoods. Is this a problem for all blacks? Only low-income black people? All Americans?

MA: Good question. I would say it’s the black community’s problem that we don’t have as many businesses as we have. The main message that I want to get out with Our Black Year is that we have to be more accountable. This economic problem is something that should be of concern for all Americans, but the problem is our problem. And it happened, I daresay, mostly because we abandoned our businesses. But I think all Americans should feel ashamed to know that there used to be 6,400 black-owned grocery stores, representing that melting pot or patchwork that is America, and now there are only three. Until equality is reflected in the economy, America hasn’t reached its ideal.

MJ: Within the black community, your experiment got a mixed reaction. In fact, one of the biggest threats to the project came from Ebony, a black-owned magazine that went after you for trying to call it The Ebony Experiment. Were you surprised by how hard it was to sell your project to certain elements of the black community?

MA: We’re very surprised. It breaks my heart every time we go to an established, influential black business owner or black organization and we still get that: “Oh, that’s nice, buy black, good for you,” pat on the back kind of thing. That hurts. The second reaction we get that hurts is this fear, for lack of a better word, from black folks at the NAACP, or National Urban League, who make the assumption that if they say anything that has specifically to do with our community—if they say “black” and not “minority”—that it will look like we’re trying to be exclusive, be racist, take down a corporation, or something militant like that.

MJ: Actually, lots of people accused you of racism. How did you cope with that?

MA: It was awful. And especially when I think about in terms of how I grew up, who I am, it’s the farthest thing from the truth. I speak to diverse groups all the time, but when you’re giving a speech you get to go through your whole thing. If you’re just meeting someone, how do you go up to them and say, “I’m a patriotic American just like you, but for a year I decided I’m only gonna support black businesses and no one else,” and not expect them to say what everyone else says: “Well, what if I did that?” So I say the black community is suffering economically, and I thought it would be great for my family to do our best to spend money with those businesses owners that employ from our community. There’s a different pitch.

MJ: You spent a lot of time driving to faraway black-owned gas stations or fast-food franchises to buy gift cards to spend at non-black-owned franchises closer to home. Is it practical to ask people who are less well off than yourself to do that?

MA: I’m not going around saying, “You need to go out and do the same thing!” I do tell folks, “I want you to at least try it for two weeks.” And it’s not just because I want them to get into supporting our businesses. I tell people, “Go out there and drive really far, and then I want you to feel the sacrifice and feel the sense of empowerment that you get from making that sacrifice.” No, it is not practical to live the way we did. But I encourage everyone to immediately get 10 subscriptions to black-owned media, immediately get an account at a community-owned bank, immediately look for the basic services—like an alarm company, just check to see if there’s a black-owned alarm company in your community. There are. Plenty of them. For your spas, for your getaways, there are tons of black-owned hotels people don’t know about. If you practice 10 of my top 20 tips, you can get up to 30 or 40 percent of your spending.

Correction: The original version of this article stated that the Andersons lived in the same neighborhood as the Obamas. However, the Andersons live in Oak Park, while the Obamas lived in Hyde Park.

MJ: You talk a lot about the idea of economic enfranchisement. Is that another way of framing this problem you’re addressing?

MA: I think it is. When we first did this it was 2008, and we were very happy with what was going on with Barack Obama, and celebrities were involved, people wearing T-shirts and high-fiving in the streets. And we thought, what if black America were that excited about their economic empowerment? What if they were running up and down the streets saying, “Did you support a black business today?” What if they were that high-fivey, or if celebrities were behind our economic empowerment in the same way? I did not realize how absolutely left out of this economy I was until I went into a Walmart one day and looked for products made by black companies. I asked for the manager, and he happened to be black. I asked if there was any way I could have a list of their diverse suppliers, or the products that really showcase their supplier and vendor diversity. He said, “Let me talk to some folks and I’ll see.”

A week later I came back to see him, and he had made some calls for me. He said “No, we don’t have a list,” but he said he’d help me find them. And he took me straight to the ethnic hair care part of the beauty supply aisle. First of all, it was like a mile long—the Oak Park Walmart is always full of black people, so there’s a huge ethnic hair-care part there. So I said, “Okay, this is just the first stop, right? You’re going to take me to other places, right? I mean, black people can do other things. You’re going to take me to shoelaces or rulers or hamster wheels; you’re going to show me something else.” And he said, “No, this is it.” He showed me two products. It’s like, Jesus, I’m here in Walmart, great American institution. Here I am, suburban mom, trying to go shopping—this is just as American as it can get—and I want to support a black business at my big American retailer, and he’s showing me two products! How am I even a part of this?

MJ: What does your experiment tell us about differences between blacks in different socioeconomic classes?

MA: When I speak about it, I’m very vocal in saying that this initiative targets middle- and upper-class consumers. Nothing’s going to change for us if the wealthier black people don’t start spending more money with our businesses. We have the cultural problem too. For a lot of black folks, you “make it” by getting out of the community, by not buying black, by not living or socializing with black people—that’s sort of your badge of honor. So we have, in the middle and upper classes, a tougher challenge: the pride issue, not just the spending issue. Poor folks hear about what my family did and they want to throw a parade. Middle- and upper-class folks will talk about it, but I don’t see the fire in their eyes. So the disconnect between the two groups is still very palpable.

But in a lot of our events, I see that kind of thing changing: We’ll have wine tastings, but we’ll have them at the black-owned bed-and-breakfast in the impoverished community we are trying to help. So my folks are face-to-face with their brothers and sisters who are not making a lot of money, who are unemployed, who are in a struggling business. I’m not saying the Empowerment Experiment is going to bridge that gap, but it’s very intentional that we are bringing in middle- and upper-class folks. It’s not the poor folks’ problem—they’re living it, they’re feeling the impact—it’s the middle- and upper-class folks who need to step up.