The current attack on access to birth control had us thinking back to the first half of the 20th century, when contraceptive methods taken for granted today, like condoms and diaphragms, were expensive, hard to find, and often required a potentially humiliating exam by a disapproving doctor.

Of course, women who couldn’t afford or gain access to medically administered birth control had to come up with their own strategies for staying baby free. Douching was cheap, accessible, and widely advertised as a feminine hygiene product; however, as Andrea Tone writes in the book Devices and Desires: A History of Contraceptives in America, it was also the most common form of birth control from 1940 until 1960—when the oral contraceptive pill arrived on the market.

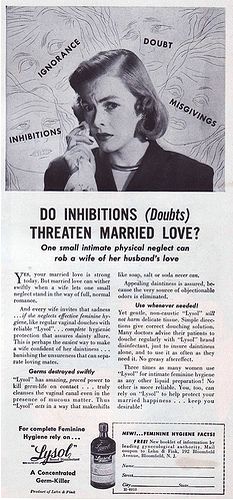

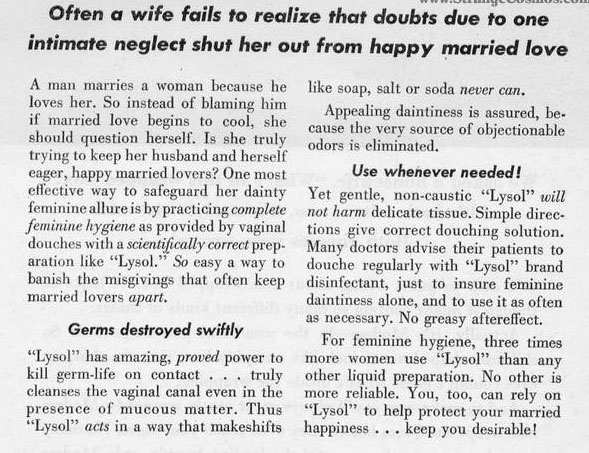

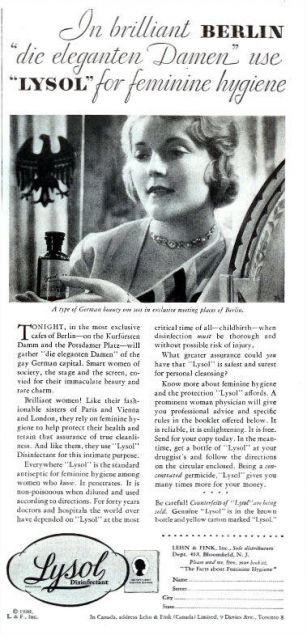

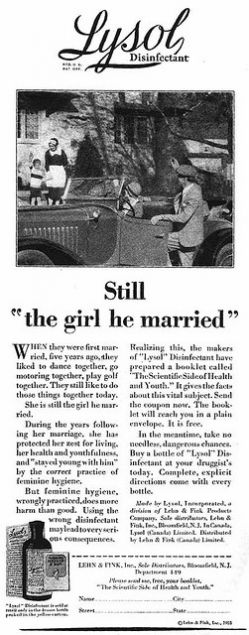

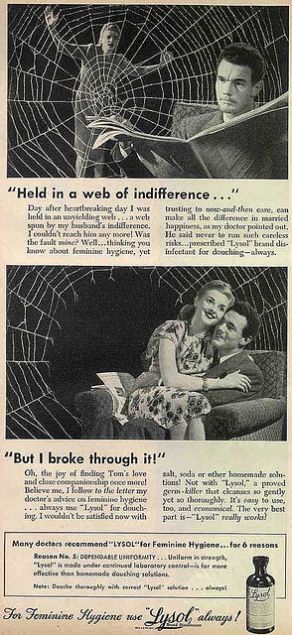

The most popular brand of douche was Lysol—an antiseptic soap whose pre-1953 formula contained cresol, a phenol compound reported in some cases to cause inflammation, burning, and even death. By 1911 doctors had recorded 193 Lysol poisonings and five deaths from uterine irrigation. Despite reports to the contrary, Lysol was aggressively marketed to women as safe and gentle. Once cresol was replaced with ortho-hydroxydiphenyl in the formula, Lysol was pushed as a germicide good for cleaning toilet bowls and treating ringworm, and Lehn & Fink’s, the company that made the disinfectant, continued to market it as safeguard for women’s “dainty feminine allure.”

Douching may have been cheaper than condoms or diaphragms and available over the counter in most drugstores, but it didn’t work. In a 1933 study, Tone writes, nearly half of the 507 women who used douching as a birth control method ended up pregnant.

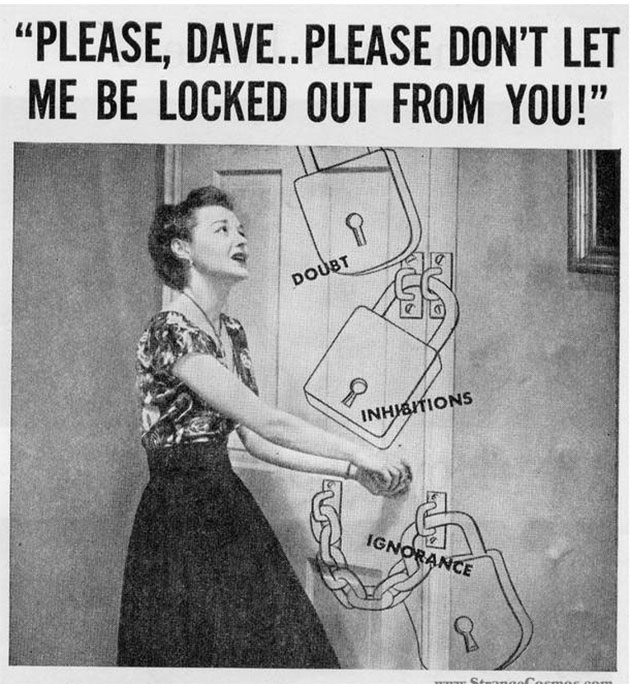

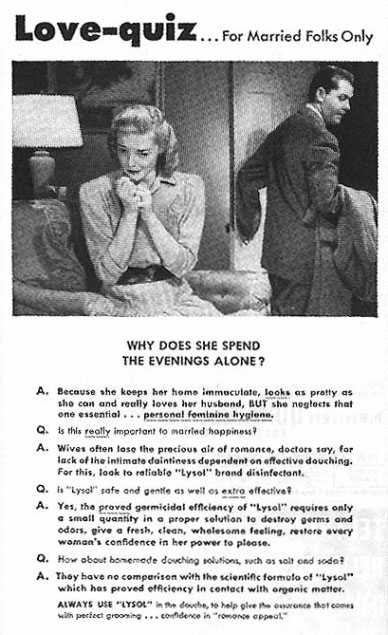

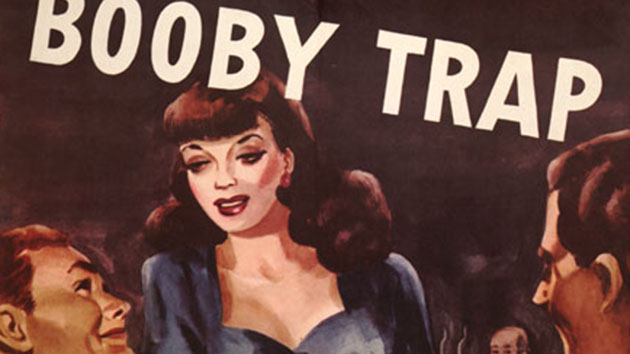

But if false advertising with highly suspect results weren’t bad enough, the ads promoted a level of misogyny and female insecurity both laughable and frightening by today’s standards. Images of wives locked out their homes or trapped by cobwebs are surrounded by text asserting a woman should “question herself” if her husband’s interest seemed to have faded. If her husband is treating her badly, the message was, “she was really the one to blame.”

These ads and the product they’re hawking are a chilling reminder of a time when most women had limited access to birth control or reliable medical knowledge about contraception. Corporate muscle moved into the void to advertise Lysol as contraception under the widely recognized euphemism of “feminine hygiene,” and as Tone writes, “the strategy won sales by jeopardizing women’s health.

Beginning in the 1920s, Lysol was advertised as a feminine hygiene product. It was overtly marketed by its eponymous manufacturer as a guard against “odors,” a term that was widely understood as a euphemism for contraception. By 1940 the commercial douche had become the most popular birth control method in the country, according to historian Andrea Tone in Devices and Desires