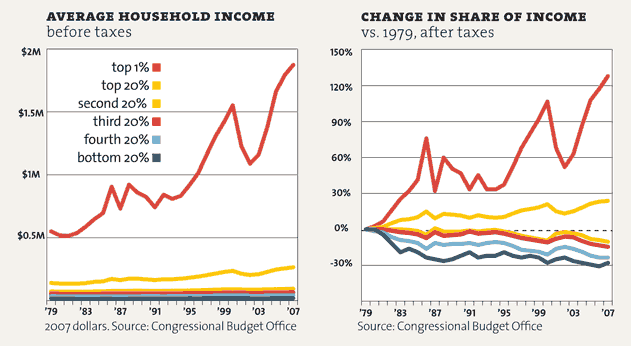

See more charts on income inequality.

The United States has become so economically polarized that your parentage is now a better predictor of your income than it is of your height and weight. So writes the Hillman Prize-winning journalist Timothy Noah in his cogent new take on how America’s rich have left everyone else behind. Out this week, The Great Divergence: America’s Growing Inequality Crisis and What We Can Do About It springs from Noah’s 2010 Slate series, which contributed to the “1 percent” meme that galvanized Occupy Wall Street. It’s a dense but informative read, harnessing a wealth of economic data to show how everything from globalization to union-busting to dual-income power couples helped the 1 percent capture the vast majority of income gains over the past 30 years. Noah’s suggestions for reversing the trend are pretty much required reading for the rest of us. I caught up with the author to get his personal take and predictions for what might be in store for us.

Mother Jones: What inspired you to expand your series into a book?

Timothy Noah: In times of economic hardship, people kind of wake up to these long-term trends. The series got a tremendously favorable reception, which was gratifying, because when I told people I was working on it, I tended to get this slightly condescending response; “Oh, good for you!”

MJ: Income inequality has grown steadily since the 1980s. Why is it only getting attention now?

MJ: Income inequality has grown steadily since the 1980s. Why is it only getting attention now?

TN: For a long time there were lots of contradictory theories about what was causing it. There was a certain amount of inequality denialism. Also, it was gradual, and journalism is not very good at covering things that are happening slowly. It really wasn’t until [economists] Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez came up with their findings in the early aughts that people really grasped the full extent of income inequality.

MJ: What is the most shocking stat you uncovered?

TN: From 1980 to 2005, 80 percent of the total increase in America’s income went to the top 1 percent. That doesn’t factor in taxes and benefits, but when you calculate it that way it’s still 36 percent, which is also amazing.

MJ: You also mention that a person’s parentage is now a better predictor of income than it is of height and weight.

TN: I call it “income heritability,” the degree to which you inherit your parents’ relative position on the income spectrum. And that is just stunning to me, because obviously we inherit our height and weight in a literal sense. We inherit our parents’ relative income only in a figurative sense, but the correlation is about as strong. That’s not what America is supposed to be about; America is supposed to be about opportunity and mobility.

MJ: Which causes of income inequality most surprised you?

TN: The major causes tend to be unsurprising: the decline of unions, for example, and the fact that the White House has been controlled more by Republicans than Democrats over the last 30 years. The fact that trade was not, at least until recently, a significant contributor was a big surprise to me. And illegal immigration didn’t seem to have had much of an impact. Also, it was interesting to me that race and gender have not been significant contributors. The income gap between men and women has narrowed and the gap between blacks and whites is essentially the same.

MJ: Why do you think union membership has declined so precipitously?

TN: I think government policy has a great deal to do with it. With the end of World War II there was some strong pushback by conservatives in the form of the Taft-Hartley law, which gave employers a lot of tools to undo the advances that had been made in the 1930s.

MJ: How can we repair the wealth gap?

TN: At the very least, I think liberals need to recognize that the labor movement is a vitally important part of liberalism. That is a strangely unfashionable idea right now. People think the labor movement incompatible with globalization. And the labor movement lost some of its prestige in the 1970s as the Rust Belt industries were declining and labor and management got locked in this very adversarial fight over sharing dwindling profits. Certainly there’s been a fair amount of corruption in the labor movement and a number of liberals find that dispiriting. But the fundamental fact is that people at the lower end of the income scale are never going to be treated decently out of the goodness of their bosses’ hearts.

MJ: How do you think conservatives will try to neuter income inequality as a political issue?

TN: If I were a conservative, my strategy would be to change the subject whenever it comes up. I think it’s a loser for conservatives. I don’t think there really is any way to take on this issue without calling into question a lot of tenets of conservatism.

MJ: You write that there is still a certain shame in America about being seen as a society of haves and have-nots. How long before we simply resign ourselves to it?

TN: I don’t know, but I think this is a hopeful moment because there is more interest in this subject than there was for the last 30 years. I think that is largely because of the Occupy movement. Piketty and Saez are not involved in politics or activism of any kind, but they created a vocabulary for activists around this notion of the 1 percent and the 99 percent. I think people are being reminded of the ways that the inequality trend does seem to be at odds with some long-standing American values.

MJ: Do you think this issue will go away if the economy keeps getting better?

TN: It would be very ironic if it did, because if the economy improves then inequality will likely pick up again, particularly at the very top. For a lot of people, the only reason to care about the fate of the economy is that in a prosperous economy you are somewhat less likely to be laid off. There is no positive incentive, because the gains aren’t being shared. And I think that is a situation that should command our attention.