Photographs by Bud Lee

Carlos Fuentes, Mexico’s most distinguished novelist, is sweating. His wife Sylvia has nearly fainted. Their teenage son, Carlos Jr., slumps against a parked car, fanning himself and listening to an Elvis Presley tape on his Sony Walkman. The sultry heat in the lowlands of Morelos is stifling.

We’re trying to make a documentary for PBS, but our camera crew, a combat-hardened team from Chile, Costa Rica, and Nicaragua, is having a hard time keeping up and they haven’t eaten. If I don’t get them a drink soon, we’ll have a mutiny on our hands.

But once Carlos Fuentes has set his mind to something, there’s no stopping until the task is finished. He’s a man of ferocious will and powerful ego; he has the tenacity of a pit bull.

Fuentes had promised to take us on a tour of the state of Morelos, the home of Emiliano Zapata, the peasant revolutionary (and subject of a novel Fuentes is researching). Our trip with him got off to a late start, but he was determined, by god, to show us everything he had planned for us to see: Zapata’s birthplace, the Zapata Museum, the hacienda where he was assassinated. All this and more—even if it killed us.

Fuentes strips off his soaking shirt and strides past green fields of sugarcane. This is beginning to feel like Mao’s Long March, as we struggle behind him lugging videotape equipment. Bewildered cane cutters look up in dazed slow motion at this strange sight, their machetes suspended in midair.

Finally Fuentes reaches a group of young girls, blackhaired, shy, and wide-eyed. Fuentes already knows, but he asks them if Zapata was killed nearby. “Oh, no,” protests the oldest girl, “Zapata is not dead. He still lives.” Fuentes turns to us slowly, a broad smile spreading across his face. “Did you hear that, my friends? Zapata lives!”  A scene of the Fuentes family in their home in 1988

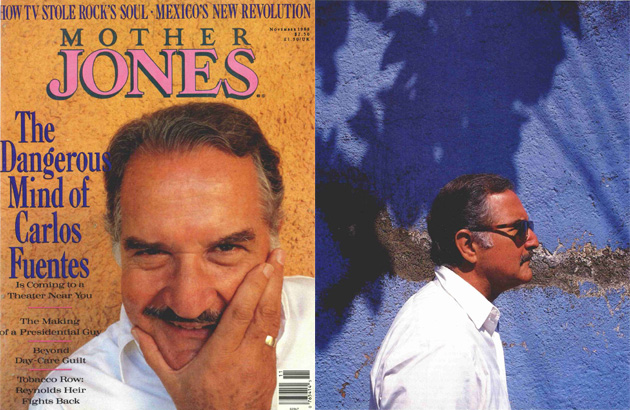

A scene of the Fuentes family in their home in 1988

It is tantamount to treason for a Mexican writer to achieve success among Yankee readers. It is considered gauche for a North American novelist to be involved in politics. And in Washington, that supremely insular town, it is still a scandal for an intellectual or, god forbid, a celebrity, to defend the Sandinistas.

Yet, Carlos Fuentes has committed all these sins, and worse yet, he shows not the least bit of remorse. In fact, he rather revels in his many contradictory personas: writer/diplomat, activist/professor, connoisseur/iconoclast, and, as he has written about himself, “the first and only Mexican to prefer grits to guacamole.” His prolific, eclectic fiction ranges from political spy thrillers (The Hydra Head) to erotic ghost stories (Aura), from baroque dream histories of the Spanish-speaking world (Terra Nostra) to caustic indictments of the frozen Mexican Revolution (The Death of Artemio Cruz). “Don’t classify me, read me,” Fuentes scolds critics of his unpredictability. “I’m a writer, not a genre.” And a heretic, not a conservative. As one might imagine, his political enemies and literary critics would like to burn him at the stake.

The latest bonfire singes the pages of the post-liberal New Republic, where a Mexican political journalist, Enrique Krauze, condemns Fuentes as a “guerrilla dandy,” a combination of Pierre Cardin and Che Guevara, who “merely uses Mexico as a theme, distorting it for a North American public.” Krauze is particularly incensed by Fuentes’ support of the Nicaraguan Revolution, denouncing him as “the tenth commandante.” The editors of the New Republic were so taken by this outburst that they made it a cover story complete with a caricature of Fuentes as a flinty-eyed Pancho Villa armed with pencils instead of bullets.

Actually, Krauze and his Yankee editors are latecomers to Fuentes bashing. Two years ago, Commentary, in a fit of neoconservative rage, proclaimed that “all Fuentes’ books are dirty” and warned that this “patrician denouncer of American imperialism” was a “left-wing utopian with an overlay of sentimental anarchism.” This crude critique of Fuentes was entitled “Montezuma’s Literary Revenge”—reflecting the taste and sophistication we’ve come to expect from the Midge Decter/Jeane Kirkpatrick set.

None of this surprises or deters Fuentes. He has seen it all before. His first novel—La Región Más Transparente (translated as Where the Air Is Clear), published in 1958—provoked wildly divergent reviews, especially in Mexico, where Fuentes’ revolutionary voice and unorthodox, European- and North American-influenced style jolted the staid, monolithic cultural scene. Ever since, Fuentes has thrived on provoking the literary, and often the political, establishment.

“I’ve lost audiences, I’ve recovered them,” Fuentes shrugs, as he sits on the porch of a friend’s magnificent house in the village of Tepoztlan, just south of Mexico City. “I’ve been thrashed by the critics. I love having critics for breakfast! I’ve been having them for 30 years in Mexico—just eating them like chicken and then throwing the bones away. They have not survived, I have!” Not that Fuentes is unappreciated. Along with his close friend, Gabriel García Márquez, and Mario Vargas Llosa, Fuentes is one of Latin America’s preeminent authors—a pioneer of the “magical realism” that has captivated readers and critics on both sides of the Rio Grande. His recent collection of essays, Myself With Others, shamelessly crowded with the names of his always-famous friends, was praised unreservedly in the New York Times. His 1985 novel, The Old Gringo, is the first by a Mexican author to become a bestseller in the United States. And when the movie version, starring Jane Fonda and Gregory Peck, is released in December, Fuentes is destined to become even more widely known in this country. He is as successful as any serious fiction writer would ever dream of becoming.

This year Fuentes received three awards that symbolize the range of his art, politics, and influence. The King of Spain presented Fuentes with the Cervantes prize, including a check for nearly $88,000. It was a radical departure from the Franco era when Fuentes’ novel, A Change of Skin, was banned in Spain for allegedly being “pornographic, communistic, anti-Christian, anti-German, and pro-Jewish.” In New York, the National Arts Club, a rather stodgy crowd, gave Fuentes its gold medal for literature in a ceremony graced by Tom Wicker, Joan Didion, and John Kennedy Jr. And in Managua, the Sandinistas bestowed upon Fuentes Nicaragua’s highest cultural award, named after Ruben Darfo, the 19th-century poet and national hero. Previous recipients included Graham Greene and García Márquez.

“They’re trying to bury me with medals,” Fuentes complained to the press. But truthfully he enjoys the international recognition he has earned and nurtured. As his old schoolmate and friend, José Donoso, the Chilean novelist (Curfew), recalls, Fuentes was “the first active and conscious agent of the internationalization of the Spanish-American novel” in the early ’60s. He was the leader of what became known as “El Boom,” the sudden surge in international popularity of Latin fiction. He has never stopped crossing borders.

“I move, therefore I am,” laughs Fuentes. But this is serious. Travel defines Carlos Fuentes. It is the essence of his art and personality. Born in 1928 to a Mexican diplomatic family, Fuentes has spent the better part of his life on the road. Today he maintains a house in the fashionable suburbs of Mexico City, but he’s rarely there. He has become an itinerant intellectual, lecturing all over the world, taking up temporary residence at one university after another, living out of a suitcase. “He’s like a shark,” observes novelist William Styron (Sophie’s Choice), who has known Fuentes for more than 20 years and journeyed to Nicaragua with him this year. “You know the shark, if it does not stay in constant motion, dies. I think Carlos moves to stay alive. I never have his phone number because it’s always changed.”

To a cultural nationalist like Enrique Krauze, Fuentes’ perpetual motion, his “rootlessness,” is his central flaw. To others, including Styron, the restlessness, the bicultural border crossing, is his greatest strength. “No one writes more eloquently about Latin America, its peculiarity, its revolutionary nature, its hopeless perplexities,” Styron argues, “or, paradoxically, perceives it with such a North American eye. I think he’s really become the leading interpreter of Latin America to the North American reading public.”

It is misleading, actually, to think of Fuentes as a man without roots, even though he no longer lives in a particular place. Wherever he travels, he carries with him his Spanish language and his Latin culture. At the same time, he brings the perspective of the outsider, even to his own country. Restless, energetic, driven, Fuentes identifies deeply with Don Quixote, sensing early in his career as a writer that “I would forever be a wanderer in search of perspective.”

Like Don Quixote, Fuentes is fundamentally a man of imagination, and his fiction is born of the clash between the world as it ought to be and the world he encounters in his travels. The disparity between his imagination and reality, the chasm between Mexico and the United States, struck him early—as a child growing up in Washington, DC, during the Roosevelt years—and the impact of that revelation has reverberated throughout his life.

Fuentes was not yet six years old when he came to the United States, where his father was counselor of the Mexican embassy. He read Dick Tracy and Superman, traded Indian Chief bubble gum cards in Meridian Hill Park, discovered Mark Twain, fell in love with the flaxen-haired daughter of the Lithuanian ambassador, shook hands with FDR, and became such a devotee of matinee movies that he won $100 in a Hollywood trivia contest.

“Mexico was an imaginary country,” recalls Fuentes. “I thought my father had invented it to amuse me. It seemed so exotic, so different from where I was living.” Reality was Henry Cooke Public School on 13th Street NW—”an American melting pot. You had blacks, Chinese, Greeks, Italians…and a wonderful teacher named Florence Painter, who really took us in hand and taught us everything—arithmetic, literature, history, geography. I get students at Harvard now who don’t have any idea where Brazil is, or Angola, or Indonesia! Where’s Mrs. Painter when we need her?

Fuentes was popular in school, “one of the gang,” until March 18, 1938, the day Mexico’s populist president, Lázaro Cárdenas, nationalized the foreign oil companies. “Suddenly there were a lot of headlines about ‘Red Mexico’ and the Mexican communists stealing ‘our’ oil, and all my friends turned their backs on me. I was an instant pariah.” As Fuentes describes the ostracism more than 50 years later, it’s evident that it still makes him uncomfortable. “That made me realize I was not a gringo,” he says emphatically. “I was a Mexican.”

The traumatic childhood experience echoes in descriptions of the US-Mexico border in The Old Gringo as a “scar,” and one can easily imagine his own wrenching separation: “Mexico…the next never frontier of American consciousness…the most difficult frontier of all, the strangest, because it was the closest and therefore the one most forgotten, most often ignored, and most feared when it stirred spontaneous was from its long lethargy…each of us carries regarded his Mexico and his United States within him, a dark and bloody frontier we dare to cross only at night.”

The Mexican nationalization of US oil interests and the sudden hostility of his peers ended Fuentes’ youthful love affair with the United States. But the jilted lover never lost his deep affection for things American: John Garfield movies, Faulkner novels, Yankee diligence, the optimism and vitality of the New Deal. Few Latin American writers have such an intimate knowledge of the gringos (including our desire to see the world reflected in our own image) or such an intense love-hate relationship with the United States. Fuentes often describes the United States as the “Jekyll and Hyde of Latin America”: “I admire your democracy; I deplore the expansionist and manipulative empire.”

During the ’60s, the US State Department—stung by Fuentes’ ardent criticism of US intervention in Vietnam and the Dominican Republic—repeatedly barred him from entering the country. And right up until this year, when portions of the McCarran-Walter Immigration Act were repealed, that legacy of the McCarthy era compelled Fuentes to apply for special permission every time he wanted to visit the United States. There is always someone to remind him he will never be a gringo.

In 1940, the boy with the Yankee accent “entered fully the universe of the Spanish language.” Fuentes arrived in Santiago, Chile, where his father took up a new diplomatic post. In the land of the poets, under the spell of Pablo Neruda, Fuentes began to write a novel with his friends at school. “It was a terrible novel,” Fuentes groans. “It was a gothic melodrama, which began in Marseille and ended on a hilltop in Haiti with a black tyrant whose mad French mistress is hidden in the attic. Shades of Joan Fontaine, wow!” There was even a climactic slave revolt. The earnest 14-year-old used to read his novel aloud to the exiled Mexican muralist David Siqueiros, who routinely fell asleep.

Fuentes’ left/liberal politics were conditioned by his boyhood travels. “You see.” he explains, “I had the triple experience of Mexico under Cárdenas, revolutionary Mexico; the United States under Roosevelt and the New Deal; and then Chile during the time of the Popular Front. These were all, in their own way, exciting democracies. And Roosevelt, to his credit, respected these experiments in Mexico and Chile. No mining of harbors. No assassinations. No intervention. None of these silly things. He respected the internal dynamic of each country. Will no one imitate him today?”

His appreciation of progressive democracy was heightened by his exposure to incipient fascism in Argentina, where his father was appointed Mexico’s chargé d’affaires. “This was at the time of Perón’s rise to power, and it was shocking,” remembers Fuentes. “A despicable man called Martinez Zuvirla was the minister of education and he had given a fascist imprint to the schools. I couldn’t take it.”

His sympathetic parents allowed their 15-year-old to quit school and wander the streets of Buenos Aires. Fuentes was ecstatic: “I became a groupie of the tango bands, I went to the low dives. I lost my virginity, which was a wonderful event! I read [Jorge Luis] Borges for the first time.”

But World War II cut short Fuentes’ romance with the tango. His father’s difficult assignment was to try to convince the Argentine regime to break relations with Hitler and Mussolini, and to protect his family from reprisals, he sent them home to Mexico. During Fuentes’ long childhood exile from his country—broken only by summer visits—his vision of Mexico had been sustained by his father’s stories. Now, returning for an extended period, the reality captivated and sometimes stunned him. For one thing, there was the stifling atmosphere of the Catholic Church—something his father, Rafael (“an incorrigible Jacobin and priest hater to the end”), had somehow neglected to mention.

Taking advantage of her husband’s absence, Fuentes’ mother, Berta, who is a devout Catholic, enrolled their unsuspecting 16-year-old in a priests’ school. It was along way from the tango clubs. “One central reality was hammered into my consciousness,” Fuentes nearly shouts, hitting himself in the head with his fist, “and that was SIN! I’d never thought about sin before. Suddenly everything I felt was natural and spontaneous was regarded as sinful. Of course, that made leftists of us all. I remember the first rebellion my friends and I staged—a celebration of Juárez’s birthday [Mexico’s first mestizo president, and secular liberal]. The priests considered him to be the big villain, the devil with horns. We staged a strike and we almost got thrown out of the school.”

As a writer, Fuentes has savored his revenge. In one of his early novels, The Good Conscience, a teenage boy in the throes of religious and sexual anguish masturbates in church while gripping the nailed feet of Christ on the cross. His short story, “The Old Morality,” features a recurring Fuentes character: the cantankerous, highly sexed grandfather who fought in the Mexican Revolution, despises the Church, and scares away priests by asking, “Do you want me to tell you where the heavenly kingdom is?” while lifting up his young mistress’s skirt.

Fuentes’ sweeping vision of the Spanish-speaking world appears in Terra Nostra—a 778-page avalanche of dense (many would say unreadable) Joycean prose, published in 1975. A reviewer in the Nation noted that Terra Nostra “is particularly Latin American in its hatred of the Catholic Church, here the embodiment of social, political, emotional, and sexual repression.” In Fuentes’ world view the archenemy is the Counter-Reformation, the totalitarian Catholic state; the heroes are the dissenters, the blasphemers—wandering Arabs, sensual Jews, free thinkers, free lovers.

Although Fuentes rejects orthodox Catholicism, he believes in a spiritual dimension, a sacred world. The Mexico City he came to know in the ’50s was a booming metropolis spiced by Hollywood gangsters, European aristocrats, and Republican exiles from fascist Spain. The sleepy provincial capital he’d imagined was already gone forever. But beneath the modern city, he saw an ancient, buried civilization: the Aztec city, Tenochtitlán. He imagined Indian gods escaping up through the subways.

“Mexico City is like Rome,” Fuentes said one morning as he strolled through the excavated remains of the Aztecs’ Templo Mayor, in the heart of the city. “There are many, many layers.” Dressed in a white suit and open-necked white shirt that reflected the bright sun, Fuentes was his own dazzling image. Strangers stopped to stare at this elegant vision. As he wandered deeper into the ruins, he began to resemble the ghostly narrator of his first novel: “…fall with me on our moon-scar city…city witness to all we forget.”

I heard the voice say: “Under the veneer of Westernization, the cultures of the Indian world—which have existed for 30,000 years!—continue to live. Sometimes in a magical way, sometimes in the shadows.” He turned, and I could see his outline against the light and haze. “The gods defend themselves against genocide, commercialization, all the abuses the Indian world of Mexico has been subjected to.”

In his emblematic short story “Chac Mool,” a statue of the rain god comes to life and drowns its art collector, a government bureaucrat. Ghosts and demons haunt nearly all his fiction, most notably in Aura, a small masterpiece about an aged, green-eyed sorceress who can conjure up her youthful beauty. Magical realism and the living presence of the past are the subterranean forces in Fuentes’ work. “I think this is a magical country,” Fuentes says with obvious pride. “Neruda in his memoirs calls it the last magic country. It is a national resource, this magic.”

But Fuentes is not lost in his dreams and the past. He is also a creature of politics and the present. In the ’50s and ’60s he was one of Mexico’s angry young men—the new generation of artists and rebels who dared to criticize publicly the failures of the Mexican Revolution and were attracted to the possibilities raised by the Cuban Revolution. Fuentes’ greatest novel, The Death of Artemio Cruz, is a furious critique of revolution betrayed by opportunists, and an indictment of Mexico’s status quo, because only half the country’s population had enough to eat.

By 1966, Fuentes had established himself as Mexico’s leading author. Like Dickens’ London and Balzac’s Paris, Fuentes’ Mexico City became, for the first time, a virtual character in world literature. But after living more than 20 years in Mexico, he was beginning to feel claustrophobic. He moved to Europe—and has never stopped traveling. Asked where he will retire one day, Fuentes is immediately uncomfortable at the prospect of staying put. “London, maybe. Or Madrid,” he mumbles, and changes the subject. That night he brings it up again: “Mexico City, you know, is committing suicide. It’s so difficult to live there.” In his most recent novel, Christopher Unborn, soon to be published in English, he calls his once-beloved city “Makesicko” and delivers an Orwellian warning, in a darkly comic style, about a ravaged, dismembered Mexico in 1992, ruled by the right wing and partly occupied by US troops. “I could settle here in Tepoztlan, where you can still breathe,” he says, looking up at the imposing mountains jutting up sharply behind the village. “But frankly, I’d be bored. I need libraries, museums, the energy of a city.”

His family seems even more cosmopolitan and removed from Mexico. His wife, Sylvia, a part-time reporter for Mexican television, is beautiful, young, blonde, sophisticated; she seems more French than Mexican. They eloped to Paris in the early ’70s (Fuentes divorced his first wife, Rita Macedo, a Mexican movie actress) and continued living there while Fuentes served as Mexico’s ambassador to France. Their 14-year-old daughter, Natasha, a pouting beauty, refuses to be uprooted anymore by her father’s endless travels, so she lives at her boarding school in Paris. Carlos Jr., 15, is an Americanized teenager obsessed with Marilyn Monroe, James Dean, and Montgomery Clift. He paints, and admires Sean Penn.

Carlos Fuentes is disciplined, efficient, and by his own admission a bit of a Calvinist when it comes to the satisfactions of hard work. One of my strongest images of Fuentes is that of a distinguished, anxious man standing on a corner in Mexico, nervously scanning the Sunday traffic for signs of our TV crew. As usual, we’re late, he’s absolutely punctual.

Being with Fuentes is an intellectual workout. Brilliant, curious, fast-talking in four languages, wildly imaginative, he can be exhausting. He can also be immensely charming—or, if he doesn’t care much for you, briskly cordial in the manner of an embassy official. He can easily intimidate, and he has a temper, but he also displays a wonderful, spontaneous sense of humor: a prankster and a ham lurk beneath the surface of that elegant Latin intellectual.

My coproducer Joan Saffa and I caught up with Fuentes in Washington last February after he emerged from a binge of writing—holed up in an office without a telephone in a semi-deserted Georgetown University building. Fuentes does not require isolation to write. I have seen him compose a lecture on a rumbling train and take detailed notes for a novel in the back seat of a speeding car. But there are definitely two sides of his personality: the private writer and the public figure. Like air and water, he requires both. Having satisfied his urge to withdraw and write, he plunges with energy back into the public arena.

After two days of videotaping, we find ourselves in New York, just past midnight, at the National Arts Club, where Fuentes has received his award. As we pack up to leave, Fuentes, utterly at home in his tuxedo, is still going strong, surrounded by friends and admirers. The next morning at seven, I meet him in the lobby of his midtown Manhattan hotel. I am still bleary-eyed; he charges confidently out of the elevator, freshly shaved, dressed in a smart trench coat and scarf—looking like the James Bond of Underdevelopment, which is what a reviewer dubbed the hero of Fuentes’ spy novel, The Hydra Head.

On the Metroliner to Washington, I sit next to Fuentes. In his best mock Hollywood gangster dialogue, he places his wrist next to mine and deadpans, “I don’t think the handcuffs are necessary.” Then as the train pulls out of Penn Station, he announces he’ll be taking a 45-minute nap. In no time, he is asleep. Less than an hour later, he wakes up, orders a Coke, and gets down to work: marking student papers, polishing his lecture. When he finishes, he scans every page of the New York Times, stopping to read all the articles on Central America. After he finishes, we begin to talk, but after awhile he starts glancing at his watch. The train is just a few minutes behind schedule, but he’s starting to get nervous about being late for his class at George Mason University in Virginia, where they are paying him handsomely for his time. Bounding off the train and into a cab, his anxiety mounts as we cross the Potomac. Only when we arrive at the suburban campus—with plenty of time to spare—does he relax.

In his seminar, he proves the ideal professor—taking his students seriously, expertly guiding a discussion of the Monroe Doctrine, going off on a tangent about the Spanish Inquisition, listening patiently, even to an earnest, insistent woman who argues for continued US military aid to the contras “to preserve democracy.” When Fuentes, rather gently, asks if the United States was concerned about Nicaraguan democracy during the Somoza dictatorship, she switches gears to say it’s not so much democracy we need to worry about as stopping the spread of international communism. A few students groan but Fuentes refuses to either patronize her or duck the issue, and the exchange continues.

Next, there is a private lunch with the president of the university, and after that, Fuentes strides into a lecture hail packed with more than 600 people. This lecture series is open to the public, and Fuentes’ first appearances were marred by right-wing pickets; he had to be escorted to the podium by security guards. But today decorum reigns. Without hesitating, Fuentes launches into a nonstop, fast-paced two-hour talk on the art and literature of medieval Spain. “He’s so passionate!” swoons a middle-aged professor from a local teacher’s college.

After a quick post-lecture sherry with the faculty, he races back to his rented town house in Georgetown just in time to feed the fish he’s promised to keep alive. He sings “Three Little Fishes” as he performs the chore, and spins out a cartoon tale of dancing goldfish in top hats and tails. It’s getting late. Fuentes disappears upstairs for a shower, another shave, and a change into an impeccably tailored dark suit, then submits to yet another one-hour on-camera interview, which he finally breaks off when a driver arrives from the Swedish embassy to take him to a dinner meeting with the Swedish foreign minister. I’m crawling into bed, while the 60-year-old writer/diplomat is still fielding questions from the Swedes.

Fuentes’ trip to Nicaragua last January was really grueling. He was on the go day and night for a week, never sleeping for more than five hours. As guests of the Sandinistas, Fuentes and author William Styron traveled in a jeep to the contra-plagued mountains north of Matagalpa; they flew in a Soviet helicopter over newly irrigated fields; they shuttled across a lake on a boat as battered and rusty as the African Queen; they visited struggling agricultural cooperatives and a shoe factory crippled by shortages; they spoke with the wounded in dreary hospital wards. And every night they ate, drank, smoked cigars, and talked for hours with the Sandinista leaders: Daniel Ortega, Sergio Ramirez, Tomds Borge, Ernesto Cardenal, Jaime Wheelock. Styron’s hound-dog face began to show the strain, but Fuentes seemed to thrive like a marathon runner.

The sharpest exchanges I overheard were between Fuentes and Borge, the tough minister of the interior who was tortured by Somoza’s national guard. In an argument about whether the contras could ever beat the Sandinistas, Borge confidently said such a turn of events was impossible because “they are going against the grain of history.” Fuentes interrupted to ask, “What about the experience of Guatemala in 1954 and Chile in 1973—didn’t they prove that the Left can be defeated?” “No,” Borge shot back. “They didn’t arm the people. That’s why they failed.”

The two men continued arguing, with Fuentes insisting, “History has a way of breaking through any ideology imposed upon it.” Later, they tangled again, this time on the subject of opposition parties. Borge said it was his personal opinion that no opposition party could ever defeat the Sandinistas at the polls. “Not now,” agreed Fuentes, “but in the future, why not?” “Only if they are anti-imperialist and revolutionary,” Borge proclaimed. “If a reactionary party won, I would cease to believe in the laws of political development.” “I wouldn’t be so sure about those laws,” Fuentes advised.

While Fuentes toured Nicaragua, President Reagan asked Congress to approve increased military aid to his freedom fighters. “There is an obsessive old man in Washington, dreaming of movie scripts which never happened actually, looking for lost lines, consumed by his personal fears,” Fuentes fumed when we finally caught up with him for an interview. “I hope that when he leaves, his fears and obsessions and paranoia will leave with him, too.”

The only person I have ever seen upstage Fuentes was Borge. He is macho, earthy, and a natural showman. Before dispatching Fuentes and Styron to visit a military field hospital in a particularly risky area, Borge joked: “I can see the headlines now: ‘Two Internationally Famous Authors Murdered by Contras.’ Not bad publicity for our cause. It would bring attention to the contra attacks on civilians. But, of course, it wouldn’t be very good for the writers!” Borge and his aides laughed hard—it’s the kind of humor popular in a war zone—but Fuentes couldn’t manage a smile.

Later, Borge succeeded in getting Fuentes to laugh by telling him how the vision of a woman’s breasts saved him from becoming a priest. There’s no stopping Borge once he’s on a roll, and with Fuentes he was in rare form. While Fuentes sampled coffee beans at a misty mountain co-op and listened politely to a manager’s description of crop yields, Borge slipped off to talk with a haggard woman and other reticent villagers. He returned, shouting to Fuentes, “The greatest harvest here is not coffee, it’s kids! This woman has 12 kids, another one has 8. You know, Nicaragua has one of the highest birth rates in the world. Only contraceptives can help—abstinence is impossible.” The campesinos grinned; this short, slightly hunched character had captured their attention. “We better get out of here before the compañeras who came with us become pregnant!” laughed Borge, as he winked at the militant woman journalist from the Sandinista newspaper Barricada, and herded Fuentes, Styron, and bodyguards into a convoy of jeeps.

In Managua, Fuentes was badly shaken by a hospital visit to see children who have been maimed in contra raids. He spoke with them quietly in soothing Spanish, and angrily waved off our camera when we intruded. Afterward he was uncharacteristically silent and withdrawn. He may speed through life, endlessly curious, racing from one country to another, skipping through the subject matter. But he discriminates. He absorbs the meaningful moments and distills them in his creative imagination. (Months after the Nicaragua trip, at the end of a long, revealing conversation, Fuentes said, “I would love to be Buster Keaton. I think he is the angel of films. He’s the innocence, the purity I’ve never seen in life. Maybe in some children. Like the children I saw in Nicaragua—the mutilated ones. They had that same purity. They had halos.”)

In a speech to the diplomatic corps and Sandinista officials, Fuentes proclaimed: ‘The defense of Nicaragua is the defense of all Latin America.” But he is sensitive as well to criticism of the Sandinistas. “I would love it if a Swiss coffee maker invented a formula for instantaneous democracy, like instant coffee, you know, whereby Nicaragua could become Sweden overnight. But no!” insists Fuentes. “Democracy takes time. Leave Nicaragua in peace. Don’t kill her people and burn her crops and schools. And Nicaragua will find her way, a Nicaraguan style of democracy.”

And how long might that take? “Well, in the case of Cuba,” Fuentes sighs, “it has taken too long. Cuba needs a dose of perestroika. Great things have been done by the Cuban Revolution in education, health, and working conditions, but the price that has been paid in individual freedom is excessive. It is time to correct this. Cuba should withdraw from the international chessboard of East-West confrontation and concentrate on itself, on the question of individual rights, freedom of expression, and democracy.”

At the end of their week in Nicaragua, Fuentes and Styron found themselves on a bus headed to Costa Rica in the middle of the night. A few hours before, Daniel Ortega had suddenly invited them to accompany the Nicaraguan delegation to a summit conference of Central American presidents. The topic of the session was implementation of the peace plan proposed by Costa Rican president Oscar Arias. A New York Times headline noted that Ortega arrived with a “Strong Literary Escort.”

“Except for the actual private meetings of the presidents themselves, Carlos and I were in on all the deliberations,” Styron said, “and it was a fascinating thing to see.” Styron watched Fuentes assume the role of diplomat: “I believe that Arias felt that Carlos was a valuable intermediary between the peace plan and Ortega. And in fact I think Carlos was able to convey some of Arias’s thoughts to Ortega. I don’t mean to say that Carlos suddenly became the eminence grise, but that people there respected him as an influential person who could contribute something.”

Ortega made concessions at the talks, which led to a cease-fire in Nicaragua and continued face-to-face bargaining with the contras. But real peace remains as elusive as ever, and Fuentes sometimes despairs that Washington will “make the hideous mistake of invading Nicaragua outright and provoking a chain reaction throughout the hemisphere…I’m simply one more individual trying to reach the American people with the message that this war in Nicaragua is a bloody waste.”

In recent years, Fuentes, the citizen of the world, has returned in his fiction to Mexican themes and settings: Burnt Water, a collection of short stories; The Old Gringo; Christopher Unborn; and the novel he is writing about the assassination of Emiliano Zapata.

“The caricatures of Zapata as a blood-soaked Attila the Hun were terrifying,” Fuentes says, pointing to old newspaper cartoons on display in a museum in Morelos, Zapata country. “People in Mexico City were shaking in fear at the arrival of this, in truth, extremely gentle, aristocratic man. I think that the bourgeois in Mexico are afraid even today of meeting the real aristocrats of Mexico because they are the Indians and peasants. They were the former princes of this realm. They’ve been here for tens of thousands of years, and they have the stamp of nobility in them, which unfortunately most of us who come from immigrants do not.”

Fuentes is too peripatetic to become directly involved in Mexico’s internal politics, but like nearly everyone else in the country he is caught up in this year’s election drama. “There has been a tremendous popular mobilization in this country,” Fuentes shouts over a faltering Mexico City phone line. “Mexico will never be the same.” He’s impressed with the “seriousness” of the centerleft opposition candidate, Cuauhtémoc Cardenas, who is, of course, the son of Lázaro Cárdenas, the president who made Fuentes discover his “Mexicanness” by nationalizing oil in 1938.

“The PRI (Mexico’s ruling party) was stupid not to negotiate with Cuauhtémoc when he pushed to open up the party, to democratize it,” says Fuentes. “This was a great strategic blunder. Now they would like to negotiate, but it’s too late. The PRI must learn to live with a real opposition. If not, all hell could break loose.”

Fuentes is a man of political concerns, but he has no desire to run for office, unlike that other outstanding Latin American writer, Mario Vargas Llosa, now a conservative and a probable candidate for president of Peru. Putting aside questions of temperament (Fuentes is far too quixotic to be a politician), he does not have a political base in Mexico, nor does he spend enough time there to develop one. Because he is so seldom in Mexico City, his long absences leave him open to the charges that he is a foreigner in his own country.

“He reminds me a little bit of Bishop Desmond Tutu,” observes Jane Fonda during a break in the filming of Old Gringo. “I mean, it’s a totally different context, but both men have such an important role internationally in helping people to understand their countries.”

Fuentes still enjoys a large readership in Mexico, and still speaks directly to the people of his country, but it does seem true that, in his politics and his writing, Fuentes has created for himself the role of ambassador, interpreter—a man ideally suited to bridge the chasm between the United States and Latin America.

Toward the end of Old Gringo, Fonda’s character, Harriet Winslow, a schoolteacher from Washington, DC, who dreams of civilizing Mexico, crosses back into the United States to escape the revolution that has unhinged her life. But at the last moment, she realizes that she no longer wants to “save” Mexico, she only wants to learn to live with it.

“So she runs for the bridge, to return to Mexico, but as she reaches it, the bridge bursts into flames and burns,” writer Joan Didion told the National Arts Club when it awarded Fuentes his medal. “Now I think that all of us would like for the bridges not to burn. But Carlos is telling us that they are going to or perhaps already have.”

Carlos Fuentes, a 20th-century Don Quixote, a man who moves in order to exist, has no desire to see the bridges burn between the United States and Latin America: He needs them to cross borders, real and imagined. But when he smells smoke, he is the first to warn us—even when we’d rather not listen.