Michael Glawogger does for documentary film what Ryszard Kapu?ci?ski did for journalism: He reinvents it as something immersive, meditative, and poetic. His films condense themes of staggering complexity—economics, labor, sex—into meticulous vignettes of everyday life. Although he has occasionally been derided for aestheticizing poverty, there’s little doubt that his audacious style is compelling. Nobody who has seen Megacities, his 1998 film about globalization, can forget those feverish New York City scenes of a hustler shooting dope and robbing his john at knifepoint, just as nobody who has watched Workingman’s Death (2005), his portrait of contemporary physical labor, can shake its images of a Nigerian slaughterhouse awash in blood.

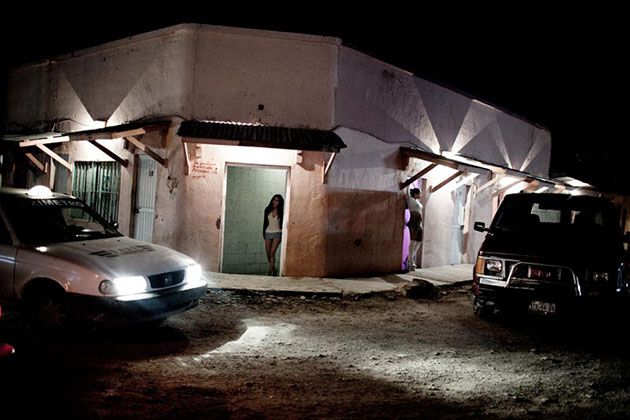

His latest film, Whores’ Glory, is a virtuoso triptych that captures the economic and spiritual tumult of prostitutes across cultures. In Thailand, women sit patiently on display inside the Fish Tank, a glass room where men can browse before buying. In Bangladesh’s City of Joy, more than 600 women compete for customers in a labyrinthine compound that doubles as both brothel and home. And in northern Mexico, La Zona is a decaying motel where women catwalk among doorways, sharply silhouetted, vying to catch the eyes of men cruising by in the dark. Glawogger has described brothels as “ghettos of desire,” but, as his film makes clear, they are also shadowlands where ancient dramas of love, lust, beauty, and despair are enacted night after night.

I recently spoke with Michael Glawogger about the challenges of capturing such a clandestine subculture. The accompanying photographs are from the companion book to Whores’ Glory, published by Orange Press.

Mother Jones: The locations you filmed pose intense logistical challenges for a documentarian, let alone one who is also taking photographs. How did you balance the two?

Michael Glawogger: Mostly I take photographs in times of research. Whores’ Glory was shot in 30 days, 10 days for each segment, but the research for each part lasted a couple of months.

MJ: Did the women respond differently to being photographed than to being filmed?

MG: Sometimes the presence of a camera is like opening a door, because many people want what Andy Warhol called “15 minutes of fame.” But prostitutes don’t want that. They know about the internet, they know their boyfriend can see them, or their parents, so overcoming those boundaries is very tough. I’ve made many documentaries, but prostitution was the hardest in terms of gaining the trust of the people being filmed.

MJ: How did you do that?

MG: I had to first convince them that I wasn’t a journalist who would yet again put out a notion about them they wouldn’t necessarily care for or who would victimize them. You know, journalists come and go. If they come twice, it’s a lot. But I come 10 times and hang out with them and share stuff. If you connect with someone just once, that’s something. But if you can connect twice, that’s something else.

MJ: The film is so lush and cinematic. Is it your ambition as a documentarian to restore beauty to lives that many outsiders might see as ugly?

MG: As a filmmaker I cannot make anything beautiful. I’m Platonic in that sense. I think beauty is the splendor of truth, so if the people I portray think they’re beautiful, they’re beautiful. I don’t make them that way. I don’t aestheticize anything. I don’t even use lights. The working girls do one thing all day: They make themselves pretty. That’s their job and their money. In a way, I had the best makeup artists, hairdressers, and art designers in the world.

MJ: How does being a man change the way these women respond to you?

MG: Whenever a man enters the realm of prostitutes he’s always regarded as a possible customer. If you enter as a woman, you’re regarded as somebody who could be in the same place. Being a man brings the perspective of flirtation.

MJ: Some of the women in Whores’ Glory talk about the burdens of being women, hardships that have nothing to do with being prostitutes but with being born female in their society. How did their moral attitude towards sex work play into this larger issue?

MG: On one hand, they don’t struggle because it’s simply their life. In Mexico and elsewhere, once they get out of these places [brothels] they have a pretty square life. In Bangladesh it’s different because they live in the brothel, it’s sort of a prison, but still there are two sides. When they think of their religion and their upbringing, they can be very moralistic. They’re moralistic about giving blow jobs. On the other hand, they have an everyday life where there’s no room for shame.

MJ: Are drugs and alcohol common ways to numb shame? In Mexico, for instance, you filmed the women smoking crack.

MG: You can become an alcoholic working in an office in Los Angeles. It’s very easy to say because I do this shameful job I take drugs or drink, but the real reason prostitutes take drugs and drink is because prostitution is a party area. It’s not about desperation, it’s the surroundings.

MJ: Prostitution also seems like a zone of often crushing boredom.

MG: If you’re a prostitute, this is your day: You party, you have customers until four or six in the morning, then you sleep. You wake at noon, watch soaps on TV, take two or three hours to fancy up yourself, and then you start waiting for customers. That’s your life. And some days no customers come. There’s no party. There’s nothing. You sit there and wait. If you’re educated you can read books, but in Bangladesh and most other places you watch TV or listen to music or cook.

MJ: What is the typical arc of a woman’s life in a brothel?

MG: In Bangladesh there are between 600 and 800 girls in the compound. You’re either young, or when you become 40 you acquire your own girls and become a pimp mother. If you got fucked over by a guy who stole all your money or something, then you become a cleaning lady. Sometimes you become a protector girl with her wooden stick who takes care of customers who don’t behave properly. You never leave the compound though. You stay there, grow old there, and die there.

In Thailand, it’s totally free. You’re a self-entrepreneur. As a young prostitute something like 90 percent of the money stays with the girls. It’s a pretty fair trade. It’s interesting because the Thai king says there’s no prostitution in Thailand, it doesn’t exist, so the prostitutes don’t pay taxes. They can work other jobs if they want and put away money, maybe leave when they’re 40.

MJ: Did the women ever talk about how their lives might be different if prostitution were legalized?

MG: I heard them talk about organizations in Europe or America where they’re very aware of legal status. Look, prostitution will always exist in every society, so I believe in a fair trade. Open the doors for women to earn their money without having pimps. The worst thing is to criminalize it, because then you open the doors for pimps, criminals, and trading.

MJ: The prostitutes in Bangladesh have often been aggressive about defending their homes and their way of life against government intervention. It seems there’s a real lack of insight about the communities inside the brothels, as well as the social function they serve.

MG: Yes, there’s always this problem in society where people know they need these places for social peace, but the fundamentalists want to shut them down. Sometimes that’s for economic reasons, because they want to build a supermarket there. The imam will hold a prayer and say let’s get rid of the girls, but on the other hand they’re all going there.

There are so many compounds in Bangladesh, and they all have like a thousand girls. Where would the girls go if they got shut down? Where would the customers go? A young man in Bangladesh can’t even hold hands with a young woman. Without marriage there is no kissing, no holding hands, no going anywhere. So young boys can only go to the brothels for sex before marriage.

MJ: Has the internet changed the way in which men in these societies seek out women for sex?

MG: They know about YouPorn and all that. The prostitutes hate it. They say the young boys get all these ideas and come there wanting blow jobs and wanting to fuck them in the ass. In a way it’s bad for business because men ask for a lot more than they used to. In Bangladesh a prostitute normally wouldn’t even undress for a man. He pays, she pulls up her sari, and he’s done in 20 seconds. In the Bengali language, there’s not a real word for blow job. They call it “doing the ice cream.”

MJ: What part of the film do you feel the deepest connection with?

MG: For sure Mexico. La Zona is such a closed area, a dangerous, outlaw area. My time in the Zona was a time outside of society, almost out of the real world. And the girls there had such a sense of irony and sarcasm. They were also really interested in my film. They’d be like, “Thank God we live in Mexico, because our kind of prostitution has a heart. We wouldn’t want to sit behind a glass cage or be sold by our own mothers. We have free will.”