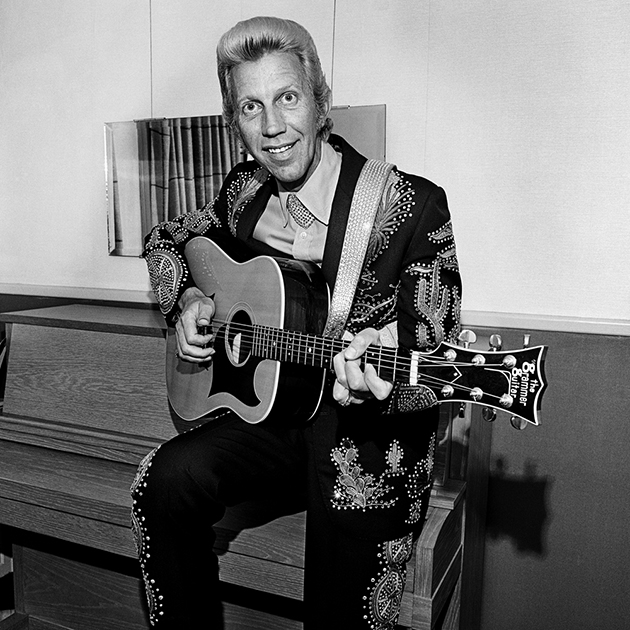

Dolly Parton, Symphony Hall, Boston, 1972Harry Horenstein

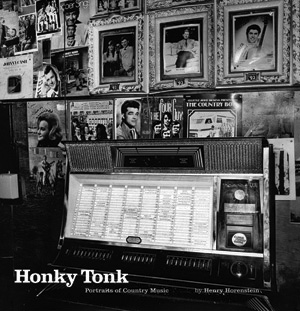

One look at Henry Horenstein’s new photo book Honky Tonk: Portraits of Country Music, out this month from WW Norton, and you’ll get a solid taste of what I love in music, a sense of authenticity. However you want to define that loaded word, you’ll get a sense of what I mean as soon as you open this book. Sure, country music in the ’70s was every bit as show-biz as any other genre. But here you get a look of something real: real people, real country music, real living. Real America, or at least piece of it. The title is a hint at what you get inside: country music (not just country musicians). The cover says it all: a stark, simple photo of a Rock-Ola jukebox pushed against a wall covered with signed promo photos and album covers.

One look at Henry Horenstein’s new photo book Honky Tonk: Portraits of Country Music, out this month from WW Norton, and you’ll get a solid taste of what I love in music, a sense of authenticity. However you want to define that loaded word, you’ll get a sense of what I mean as soon as you open this book. Sure, country music in the ’70s was every bit as show-biz as any other genre. But here you get a look of something real: real people, real country music, real living. Real America, or at least piece of it. The title is a hint at what you get inside: country music (not just country musicians). The cover says it all: a stark, simple photo of a Rock-Ola jukebox pushed against a wall covered with signed promo photos and album covers.

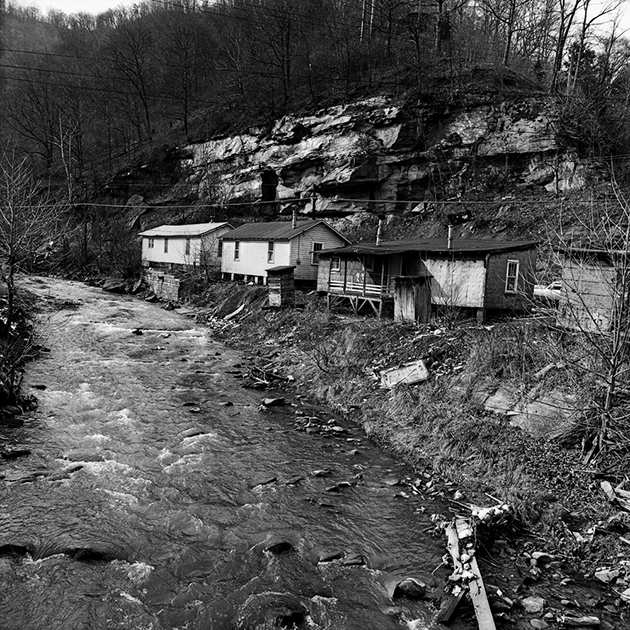

As a young photographer, Horenstein more or less adhered to the sage advice handed down to nearly every photographer: Shoot what you know, shoot what you love. He loved country music, and set out to shoot the honky tonk clubs of the East Coast and South in the early- and mid-’70s.

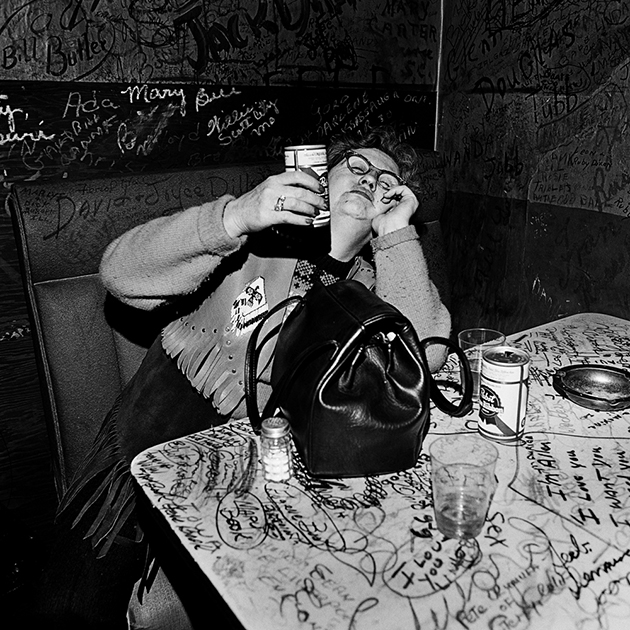

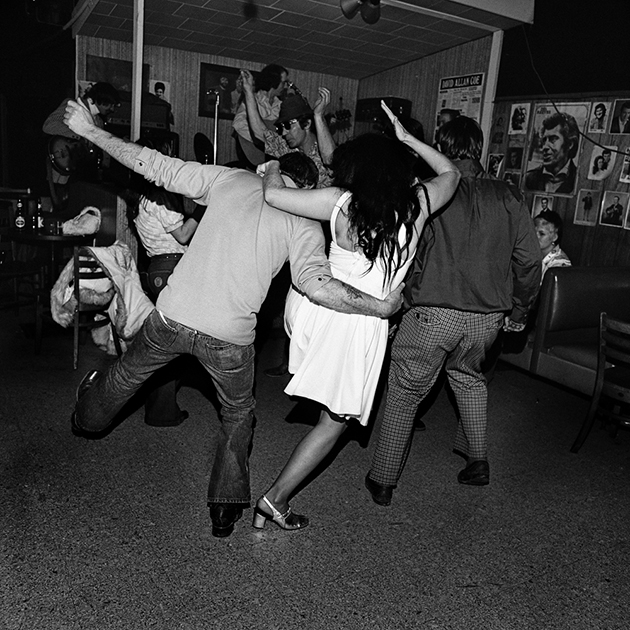

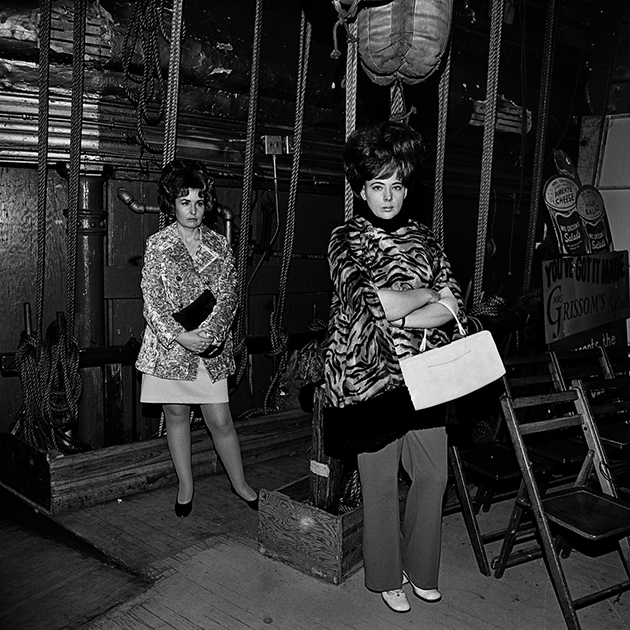

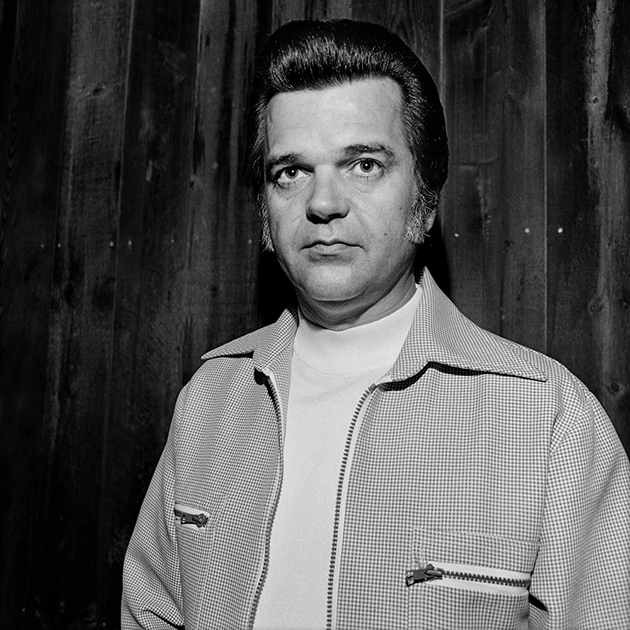

While he shot a number of country legends in their prime (and plenty on their decline), what really makes this book a gem are the photos of the people. The fans. The barflys. Horenstein puts you among the trees at the Lone Star Ranch in New Hampshire, he takes you onstage (and backstage) at the Grand Ol Opry, and, best of all, he sits you down in the booths at Tootsie’s Purple Orchid Lounge in Nashville.

You might be tempted to take a swing at my claim of realness here. After all, anything viewed from the distance of three or four decades tends to look somehow authentic. The good old days. Simplier times. All that baloney. The bulk of these 120 photos of country musicians and their legion of fans are from the mid-70s. But if you look closely, you’ll see that Horenstein is still at it, sneaking contemporary photos into the edit.

It’s the addition of these newer photographs, some as recent as last year, that make this edition different than the out-of-print version released in 2003 by Chronicle Books. That, and the nice hardcover jacket. Horenstein’s style has evolved a bit—it’s more polished now—and while the newer photos are well-integrated with his earlier, bare-knuckle work, they don’t necessarily add much to the mix. His work also leaps from mid-’70s—with a smattering of early-’80s shots—to the present, so you’re not quite getting what might have been a nice chronology, or evolution of the country scene.

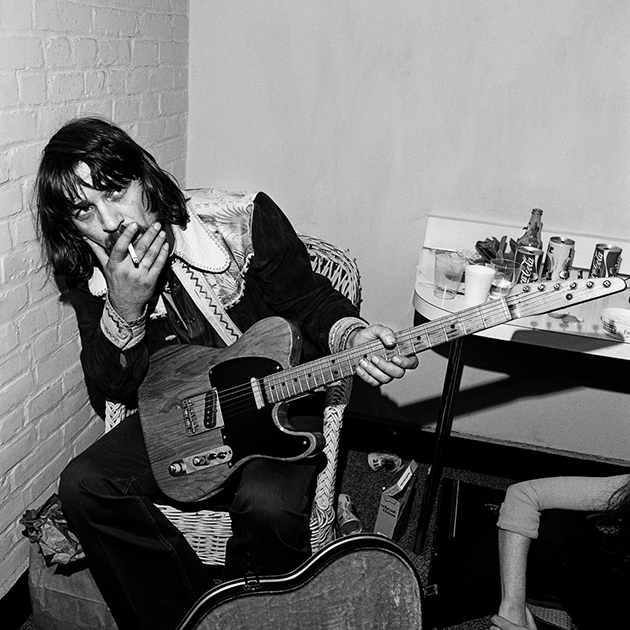

The best performer shots are the old ones. Among others, we see a young Dolly Parton, Tammy Wynette and George Jones, mother Maybelle Carter, Charlie Monroe, Hank Williams Jr., Ernest Tubb, Jeannie C. Riley, Minnie Pearl, Boxcar Willie, Lester Flatt, Emmylou Harris, Jerry Lee Lewis, Waylon Jennings and tons more. These are priceless.

By the time Horenstein started his project, country fans were already deriding Nashville for caving to pop music. Which may have been true at the time, but set against the backdrop of what passes for country music today, his photos look achingly authentic—cigarette burns, beer stains, nudie suities and all.