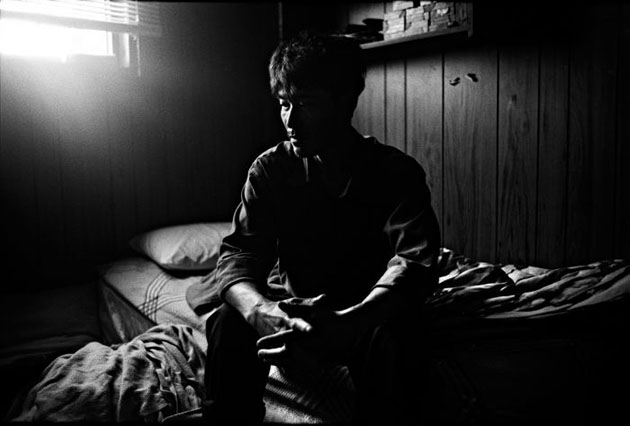

May 20, 2011, Charlottesville, Virginia. A Burmese man, a relative of Ehney Ser, finally at home.Gabriele Stabile

Imagine for a moment that some terror has engulfed your country. War, let’s say, or genocide. Life is suddenly unbearable, so you hire smugglers to transport you and your family across the border to safety, maybe to an encampment on the edge of a foreign city. You live there under the constant fog of deportation, making few friends and scouring the news for word of your country’s return to sanity. It never comes.

Then one day you are notified that the United States has agreed to process your family as refugees. One of the first things you see upon entering America is a hotel near the airport, nondescript and beige amid a scrawl of interstates. This is what you’ll call home until morning, when once again you’ll board an airplane destined for your city of permanent resettlement in America.

While they don’t exactly offer an auspicious welcome, hotels like this signal salvation for more than 64,000 refugees a year. The exodus is documented in Refugee Hotel, the latest volume in the Voice of Witness series. Launched in 2004 by author Dave Eggers and physician/scholar Lola Vollen, Voice of Witness is a nonprofit organization that uses oral histories to illuminate human rights crises around the world.

The first book in the series to combine photojournalism with firsthand testimonies, Refugee Hotel depicts acculturation with all its ironies. Refugees shuttle between agencies that chaperone job placement, ESL classes, and social orientations, celebrating milestones that, had they occurred in their native countries, would signify failure. Former doctors must now work as auto mechanics; former professors are now housekeepers; formerly middle-class families are now wedged into shabby apartments living paycheck to paycheck. What makes this otherwise untenable change of fortune so ennobling is that in America, at least, there is the possibility of living without fear. As Farah Ibrahim, a refugee from Iraq, says: “I’m learning to dream again.”

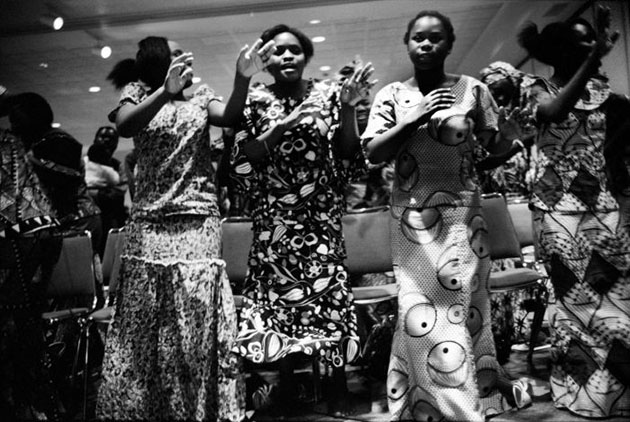

Of course, the dream isn’t always comforting. Families struggle to nurture their traditions in the washout of American pop culture, while many also find themselves overwhelmed by the country’s imposing bureaucracies. Refugees forge enclaves in cities as varied as Amarillo, Texas, Erie, Pennsylvania, and Mobile, Alabama, where together they combat a prevailing sense of “otherness.” In Mobile, African refugees have built the True Light Pentecostal Church, a haven where parishioners reflect upon their journey in both political and spiritual dimensions. In the words of Ann Githinji, a refugee from Kenya: “They [refugees] see America as not only a place to live in peace for the time being, but as a place where they can become citizens, and live legally. Still, they see this place, Mobile and everywhere else, as a stopover on their way to heaven.”