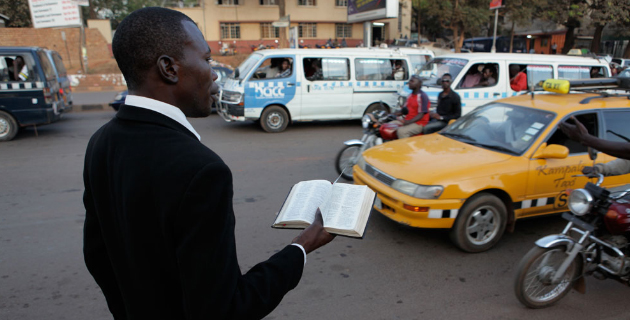

A street preacher in Kampala, UgandaDerek Wiesehahn

The Supreme Court’s recent decisions on same-sex marriage were a sound rebuke to religious conservatives who have sought to demonize gay Americans and prevent them from sharing rights that their fellow citizens take for granted. But American evangelical groups, undaunted by their losses in America’s culture wars, have been taking their messages—good and bad—to the multitudes of Africa.

Uganda in particular has been a hotbed of American evangelical activity. The landlocked nation has seen more than its share of sorrow, from genocide to the horrors of AIDS to the guerilla terror of Joseph Kony’s Lord’s Resistance Army. It has repeatedly ranked among the world’s worst for human rights and freedom of the press. Last year, Foreign Policy and Fund for Peace classified Uganda as a “failed state.”

In recent years, the country has drawn ire for its Anti-Homosexuality Bill, known more ominously as the “kill the gays” bill because, if approved, it would mean the execution of recidivist homosexuals. There are plenty of live-wire personalities, not the least of whom is the Reverend Martin Ssempa, who’s found that there’s nothing like gay fetish porn for stoking a congregation’s bloodlust.

In 2008, the Ugandan tabloid Rolling Stone published the names and faces of 100 gay rights supporters under the headline “Hang Them.” Among them was David Kato, an activist who has been called “the father of gay rights” in Uganda. Kato successfully sued the tabloid for endangering his safety (and won about $640) but was bludgeoned to death under mysterious circumstances not long after. His supporters believe anti-gay factions were behind the murder.

But perhaps the biggest actors in Uganda’s gay rights drama are the American evangelicals who travel there every year by the thousands to spread their Gospel from the far pastures of charismatic Christianity. One of the most powerful groups is International House of Prayer (IHOP), a Kansas City-based mega-church with hundreds of outposts, more than 1,000 staffers, and a declared mission to secure a “million new souls and a billion dollars” for Christ by 2020.

To this end, the church maintains a 24/7 “prayer room” that has streamed live Gospel music and prayer continuously since 1999. IHOP also has its own university where young Americans learn how to enlighten poor people 8,000 miles away about the nightmares of hell. Under the leadership of pastor Mike Bickle, IHOP has poured millions of dollars into Uganda—much of it filtered into local churches and missions with explicitly anti-gay agendas.

This is the story that Academy Award-winning filmmaker Roger Ross Williams captures in God Loves Uganda, a documentary that premiered at Sundance in January and is now showing on the film festival circuit. It’s an eye-opening and ultimately infuriating account of evangelicalism run amok. While Williams takes care to present both sides of the debate—his empathetic portraits of American missionaries befouled by good intentions are commendable—what emerges is an indictment of imperialism, conservatism, and opportunism masquerading as charity. I caught up with Williams by email to chat about sex, Uganda, and the evangelical right’s determination to conquer both.

Mother Jones: What compelled you to tackle this subject?

Roger Ross Williams: My last film, Music by Prudence, took place in Zimbabwe, and while there I was struck by the popularity of conservative Christianity in sub-Saharan Africa—there was a church on every corner. After I read about Uganda’s now famous “kill the gays” bill, I wanted to explore the religious forces behind it. As a gay man, I wanted to understand the folks who wanted to kill me and why.

MJ: Did you experience any hostility while filming in Uganda?

RRW: It was very intimidating and scary. I was outed. Someone sent an email to Reverend Joanna Watson [an American missionary] saying that I’m gay, and she sent it to all the anti-gay pastors in Uganda. One of them said, “We’re going to take care of this guy.” When I was confronted by them I didn’t know what they were going to do, but they decided to pray over me. They said they were going to cure me. That didn’t work, of course.

Roger Ross Williams

Roger Ross Williams

MJ: You’re from a very religious family. How did that background play into the film?

RWW: I grew up in a Southern Baptist-style church with a choir, a band, and music, but I’ve been asking myself my whole life, “Why is my own church, my own community, rejecting me because of my sexuality?” Imagine that you’re a gay man and you’re spending all your time with people who believe you are possessed by the devil. Or, in the case of a lot of Ugandans, with people who believe you should be killed. Someone told me once that I’m worse than a dog, I’m the scum of the earth, so for me it was draining. When I would come back from a shoot I would be wiped out emotionally for two weeks.

MJ: Was it difficult to maintain objectivity given the environment in Uganda?

RWW: I didn’t go with an agenda. I’m not an activist at all. I’m a filmmaker, and I wanted the people involved to tell their own story. I didn’t even know the extent of American obsession with Uganda until I got there and saw it. You ride in the plane and it’s filled with American missionaries. Uganda is the No. 1 destination for American missionaries in the world.

MJ: What did you find most surprising? For me, it was your film’s claim that American aid to Uganda tripled in the wake of Uganda’s parliament proposing the anti-gay bill.

RRW: Not only that, but the Family Research Council even lobbied Congress not to release a statement condemning the bill. This was a big red flag for me. Why so much interest in Uganda? Why are American conservatives lobbing for hate? The answer is that they feel they have lost the culture war here at home and are exporting their outdated ideas to the developing world.

MJ: How did you approach IHOP? What kind of film did they think you were making?

RRW: I told them I was making a film about their missionary work in Uganda and that I was going to address the anti-homosexuality bill. They commented that I was part of the gay agenda but decided to participate anyway. They believe strongly in what they are doing in the world, and they prayed a lot for my salvation and for the film to portray their version of the truth. I think it did.

MJ: Did IHOP restrict your access?

RRW: Yes. They did not want me to film certain aspects of their missionary work, and I was not allowed to speak to the young missionary kids without Jono, their media director, or another IHOP leader present. I was told that the young missionaries may not stay on message and could say something stupid.

MJ: People close to IHOP, as well as national media, have likened it to a cult. Based on your experience, is that a fair characterization?

RRW: I think there are scary cult-like practices at IHOP. To be honest, the place scared me to death. There was way too much blind devotion, and the anti-gay and cure-homosexuality books in the bookstore were disturbing, to say the least. What I saw was a lot of young people who were searching for some meaning in their lives. They were falling over each other to restrict their natural sexual urges, and I even heard they have sort of a buddy system to make sure they are not looking at porn. That restriction alone would drive anyone right to the XXX section of a bookstore.

MJ: What were your impressions of the missionaries?

RRW: I always compare them to the kids who naively signed up to go to Iraq to fight terrorism. They are just the foot soldiers in the spiritual war that Mike Bickle and Lou Engle are waging against what they consider sin. They will say it is biblical truth, but the Bible says many things, and you don’t see anyone saying that slavery is okay or that we should not eat shellfish. Why the fascination with sex?

MJ: Did the kids understand the extent to which IHOP is invested in Uganda’s anti-gay campaigns?

RWW: They understand that there’s a battle. As Mike Bickle said to me, there is a spiritual battle going on in the world, and he believes that in America marriage between a man and a woman will become illegal. He believes there will be a war. He believes it’ll begin in schools and the Christian kids will rise up and slay the non-Christian kids. This was an on-camera interview! But I didn’t put a lot of this more extreme stuff in the film because I want it to be a dialogue between different factions of Christianity.

MJ: It seems like fear is a big factor in this brand of evangelism.

RRW: I think IHOP is a master at exploiting this in young people. My first day shooting I felt like I was on the set of Jesus Camp. It was fascinating and disturbing, and I thought: Who are these kids? In the bookstore there are countless books and CDs of Bickle speaking about demons and spiritual warfare and inciting all this fear of the end times. Then they bathe everyone in the calming, trance-like world of the global prayer room: There are musicians playing 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and they have not stopped playing for 13 years. When you are in the prayer room you forget about the outside world and fall into a Christian-rock coma, and nothing else seems to matter. You forget your problems and become part of a community. The musicians are good and their music is catchy—it pulls the kids in in droves. Mike Bickle admitted to me that the music was a big part of their success at attracting young people.

MJ: There’s a quote in the film that Uganda is “a dumping ground for extreme ideas.” What makes the country so vulnerable to foreign manipulation?

RRW: What happened in Uganda was that Idi Amin [Uganda’s dictator from 1971-79], who was Muslim, outlawed Pentecostalism and charismatic Christianity, so those movements went underground. They were also smart in that they identified with the pan-African movement. After the fall of Amin, they came aboveground and helped rebuild their country, which had been devastated by years of civil war. Americans were sources of power, so Uganda welcomed American faith leaders. The day Amin fell, Mike Bickle, the leader of IHOP, was there on the ground with bullets flying over his head. He was there with a bunch of Christian leaders.

MJ: The film has received enormous critical acclaim, but hasn’t gone unscathed. How do you respond to charges that you are depicting only the extremes of evangelicalism: Scott Lively and Lou Engle, for example.

RRW: I would argue that Lou Engle is not on the fringe. He was a roommate of Sam Brownback, who is now governor of Kansas [Engle and Brownback shared an apartment for seven months in 2000 after a fire destroyed the latter’s building]. He organized Texas Gov. Rick Perry’s famous prayer rally, “The Response.” You can see him praying with Congresswoman Michele Bachmann to end Obamacare on YouTube. Recently, an evangelical professor from Regent College, John Stackhouse, was asked to have a discussion with me at DOXA film festival in Vancouver. He used the opportunity to attack the film, and wrote a factually incorrect review in Christianity Today. In his review he tried to say that Lou was marginal, but nothing is further from the truth.

I agree that Scott Lively is marginal, and that is exactly why evangelicals must not let him speak for them. But in Uganda, Scott Lively is allowed to address the parliament for five hours, and his hate-filled message led directly to the anti-homosexuality bill. Why have no evangelical leaders stood up and said he does not speak for us?

MJ: How do ordinary Ugandans respond to this influx of young, white, religious Americans?

RRW: They embrace them because they represent everything that America represents: money, power, and freedom. Why else would you see an old Ugandan woman respectfully listen to a 22-year-old white girl from America telling her what she should or shouldn’t believe? What is so attractive about Uganda for missionaries is that they have free rein. They can go anywhere they please—schools, hospitals, the parliament. The first lady of Uganda is a devoted evangelical and beloved by the faith community. At an evangelical conference in Argentina, one minister said, “Mama Janet has given us the keys to Africa.” She has done that by creating a nation that has embraced a Dominionist form of Christianity that believes that Christians have a God-given right to rule the world.

MJ: Your film captures Ssempa showing his congregation gay porn to educate them about the vileness of gay sex. Do other religious leaders share his methods?

RRW: He is famous for it. Other pastors are equally extreme. I saw footage of a well-known pastor named Julius Oyet holding a Bible and saying, “This book says homosexuals should be killed.” I’ve interviewed Solomon Male as he demonstrated how gays have sex. In my New York Times op-doc, you see Pastor Male roll up a paper and point to his ass to show how they insert the penis into the anus. He goes on to explain how “everything comes out.” If you ask me, they are all a little too obsessed with anal sex. It’s all so absurd—you can’t really make this stuff up. Right now Ssempa is raising money to pass the bill. He is very active on Twitter, and uses social media to promote hate.

@frankmugisha Frank do you know that sodomy vice is against the order of nature?

— Martin Ssempa (@martinssempa) June 17, 2013

@WashingtonBlade We plan a mass “opposite sex” couples pride march to counter protest the “same sex” one!!

— Martin Ssempa (@martinssempa) June 14, 2013

MJ: Bishop Christopher Senyonjo and David Kato are, in different ways, martyrs for Ugandan gay rights. What kind of support exists for people like them who are excommunicated or rejected by the church?

RRW: There is very little support for the LGBTI community [the “I” stand for “intersex”] compared to the other side. Thankfully, human rights organizations such as the RFK Center have supported activists like Frank Mugisha and SMUG [Sexual Minorities Uganda], but there is not widespread support for faith leaders like Senyonjo. The fundamentalist faith community is light years ahead of the progressives in Africa. This has to change if we are going to make any progress. If the battle in Uganda is lost, then the outcome will be felt across the continent. Gay Africans must speak up and let everyone know they are there, they have always been there, and that they are not going away.

There is a great project called “None On Record: Stories of Queer Africa” where the African LGBTI community document and tell their own stories. I think that is the legacy of David Kato—there has to be a civil rights movement led by queer Africans challenging the Martin Ssempas of the world. We used to march in the streets of New York in the ’80s saying, “We’re here, we’re queer, get used to it.” Africans need to do the same thing.

MJ: The film shows IHOP rallying thousands of American supporters behind California’s Proposition 8. How involved is the church in domestic politics?

RRW: IHOP has 1,000 full-time employees, a $30 million per year operating budget, and their global prayer room is one of the most popular tourist destinations in Kansas City. They count among their members very powerful leaders from the Christian right, the leaders of tea party rallies, and the speechwriter for Sarah Palin. I think they have a clear mandate to change America from a political perspective. Mike Bickle himself told me you cannot separate politics from the Bible.

American Christian politicians like Sen. James Inhofe (R-Okla.) are obsessed with Uganda because they can win the culture war there that they see themselves losing here in the US. They see Uganda as a religious experiment. Sen. Inhofe is part of the Washington organization known as “The Family,” and they count many politicians as their members and throw the National Prayer Breakfast every year. Every recent president has attended that breakfast. The author of the Anti-Homosexuality Bill in Uganda is the Ugandan representative of “The Family,” and he not only attended the US prayer breakfasts, but throws his own version in Uganda. It’s all well documented.

MJ: Have ordinary Ugandans benefited from the presence of American evangelicals?

RRW: American evangelicals have done great work in Uganda. They have provided food and shelter to millions of orphans, built schools, and administered health care. They helped make Uganda an economic success story in Africa. Uganda can greatly benefit from American evangelicals if they separate the Scott Lively extremists from the Rick Warren type of moderate evangelicals.

MJ: What affect do you think the Supreme Court’s recent rulings will have on evangelicals in Uganda?

RWW: The American evangelical community, fundamentalists, have all said it’s game over in America, but we’re winning in the Global South and in the developing world. While people are celebrating in America, we are winning the battle in the rest of the world.

MJ: A film like this urges people to act. What do you hope your viewer’s response will be?

RRW: If the audience wants to get involved, they should go to our website and sign up for our newsletter. We will be asking our audiences to engage in different ways, including writing to their local congressmen and screening the film in their church.