Editor’s note: In 2012, Mother Jones contributing photographer Matt Slaby began photographing heroin users around Denver, along with the places they overdosed. “In Xanadu” was a personal project, like many other Slaby has taken on. This time, though, rather than just turning to an editorial outlet like a magazine or newspaper to publish his work, he teamed up with the Denver-based nonprofit Harm Reduction Action Center in a mutual effort to raise awareness and to potentially help the people he photographed and others like them. —Mark Murrmann, Mother Jones photo editor

“This is the last thing I saw when I overdosed. I was injecting heroin in a hidden alley so nobody could see me. I didn’t want to get caught; I didn’t want anyone to know. Heroin was more powerful than my fear of overdosing.”

One of the fundamental problems faced by health care advocates working with injection drug users is a generalized, public perception that the issue is isolated to people and places outside of the normal social sphere. Generally speaking, our tendency is to dissociate our ordinary experiences—the people we know and the places we go—from things that we consider dangerous, dark, or forbidden.

In the arena of injection drug use, the consequence of this mode of thinking has been historically devastating. Instead of crafting public policy that works to minimize the harm caused by addiction, our trajectory tends towards amplifying consequences for anyone that wanders outside of the wire and into these foreign spaces. Rather than treating addiction as a disease, we treat it as something that is volitional and deserving of its consequences. Accordingly, our policies view the contraction of blood-borne pathogens and the risk of overdose as deterrents to the act of injecting drugs.

These “consequences,” of course, have little impact on rates of addiction; they do, however, all but ensure the continued spread of HIV and hepatitis C. Moreover, possession and distribution of Naloxone, a drug that counters the effects of otherwise fatal opiate overdoses, remains criminal in many areas throughout the world.

This body of work is an attempt to combat the notion that addiction exists elsewhere. This series pairs portraits of active and recovering injection drug users with places significant to their stories, creating diptych sets that illustrate the issue as something that is neither foreign nor deserving of moral stigma. In short, this work attempts to showcase the issue in normative terms: These are people we know and places we go. —Matt Slaby

“You’ve probably said hi to me on the street. I’m your friend. I’m not just someone you’ve seen around, I am someone you know. When I first learned to inject I was only 16 years old. It didn’t happen in a dark alley or some dingy bar; I learned to inject drugs in these suburban apartments across from my grandmother’s home.”

“When I introduce myself to others, I usually tell them I am an actor. Sometimes I tell them that I have HIV. Occasionally I tell them that I inject heroin. If you know me really well, I’ll tell you about the time I overdosed right there in the picture. That’s my living room.”

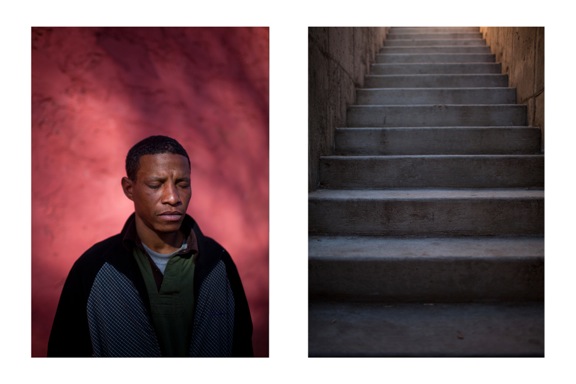

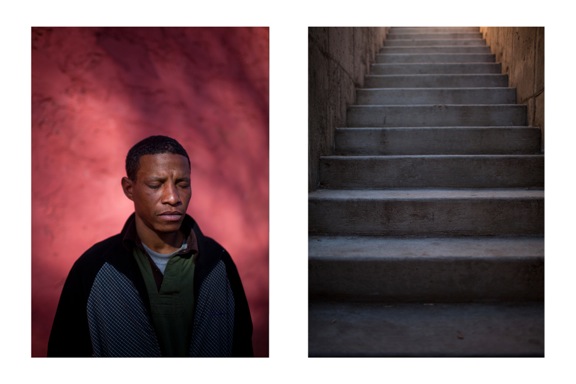

“‘This does not look like skid row,’ I thought as I walked up to the condominiums. This is the kind of place everyone knows. It is ordinary. So was my overdose. I shot heroin in the stairwell where I lost consciousness. Thankfully, somebody found me.”

“I live in this camper with my dog. I inject drugs here too. I use 1,820 syringes each year.”

“The first time I injected heroin I got hepatitis C. A year later, I overdosed under the bridge there in that picture. If you drive in the city, you probably cross over this spot dozens of times each week. Fear of death and disease won’t stop me from using heroin.”

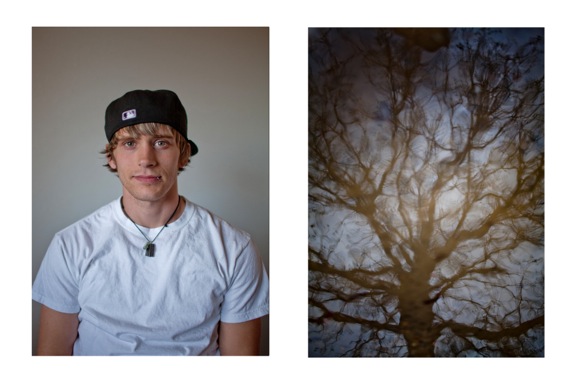

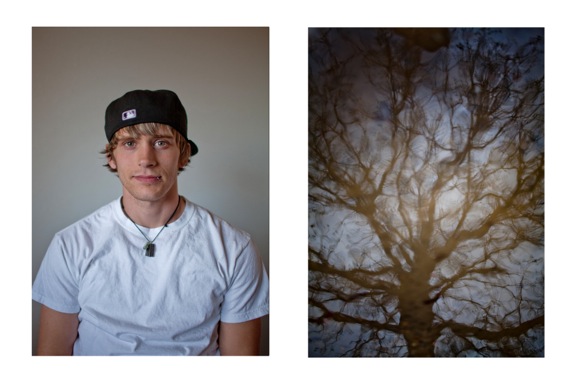

“I look like your son, not a junky. It’s been two years since I locked myself in a portable toilet near the state capitol and overdosed on heroin. It happened right there, on the exact spot where a puddle of rainwater reflects the trees of Civic Center Park. The thing is, overdoses happen all the time. They happen to people we know. They happen in places we go. It happened to me.”

“When I was diagnosed with lymphoma I was prescribed a heavy regimen of pain killers. Cancer hurts, but with treatment, it went away. My dependency on opiods did not. Two years later, this is where I live: in a car, under the interstate. I did not choose to get cancer; I did not choose to become dependent on opiods.”

“I doubt you would guess, but I have injected drugs for more than a decade. Two years ago I overdosed on heroin right there, in the picture. You have probably walked by it a dozen times. Right there, in that picture.”

“After a decade living as a homeless youth, you may be surprised to learn that the most traumatic thing that happened to me didn’t happen to me at all. It happened to my closest friend, Val. She died of a heroin overdose. Right there, in the picture. She was my friend. She was someone’s daughter. Sobriety has taught me a lot about the thin line that separates us all. Val was someone you knew. She probably served your coffee. She probably even greeted you with a genuine smile.”

Helen wears a pin of her late son, Leo. Leo overdosed on heroin in the house pictured on the right. Overdoses are almost entirely preventable.

“I overdosed on heroin in the parking lot in this picture. It wasn’t my first overdose and it may not be my last. I know the risks of doing heroin, but drug dependency is strong.”