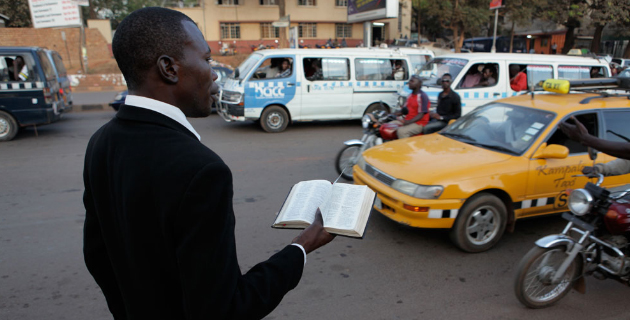

Wangechi MutuPhoto: Kathryn Parker Almanas

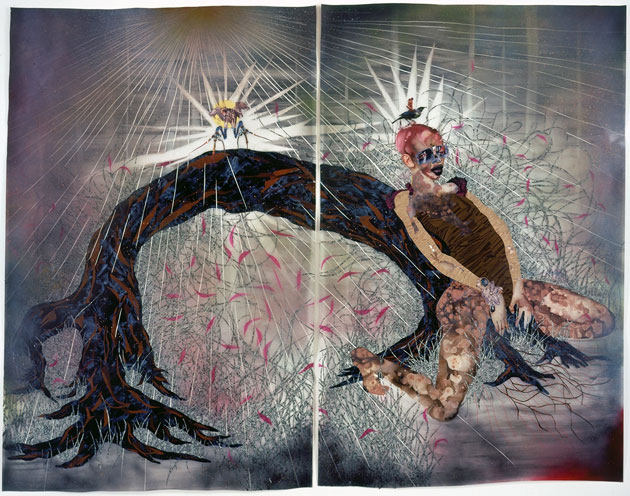

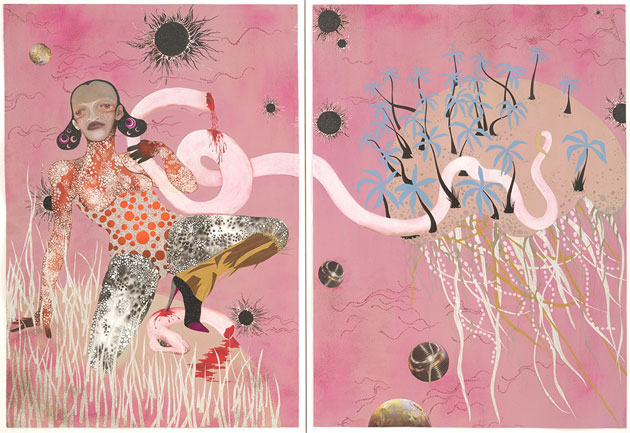

“The power for me is to keep the story of the female in the center, to keep discussing and talking about women as protagonists,” Wangechi Mutu said in a video introduction to A Fantastic Journey, her recent exhibition at Duke University’s Nasher Museum of Art. For the casual art fancier who happens upon it, as I did this summer, the exhibition was like embedding in Mutu’s mind: Black globes of crumpled plastic hang on strings suspended from the ceiling, a looping video of the artist devouring cake flickers on the floor, and triumphant warrior women occupy magnificent collage landscapes on the walls.

Mutu, a Brooklyn transplant via Nairobi, deploys mixed media to grapple with themes of consumerism and colonization, of gender and race—and war. Her large, lush collages draw from images familiar to us, such as magazine photos of bare flesh and car engines, which she transforms into works that are mysterious, beautiful, and somewhat terrifying. Her animated short, The End of eating Everything, done in collaboration with the singer Santigold, depicts a colossal machine/beast/planet feeding on black birds while floating in a vast industrial dead space. In an interview discussing the piece, Santigold praised Mutu for her “explosive renewal” of artistic expression at a time when vapid materialism dominates the popular culture.

Mutu’s work has shown all over the globe, from New York’s MOMA to London’s Tate Modern. On Friday, her Fantastic Journey continues with an opening at the Brooklyn Museum. Mutu took a break from installing to speak with me about warrior women, consumerism, and why magazines are the “fecal matter of society.”

Mother Jones: Let’s talk about your homeland. How does Kenya influence your work?

Wangechi Mutu: It is rapidly developing its industry and manufacturing, and its cultural identity as a new country. We had a humongous history pre-British, and when we were colonized and violently reshuffled, we had to decide who we were again. We couldn’t rest on the stories and the cultures of our great-grandparents. A lot of it had been torn out and thrown away. As Kenyans, we’ve had to decide, “What the hell is Kenya? Who are we? What’s our language? What’s our visual history? What’s our legacy?”

We have this cobbled-togetherness that comes out of a poor country aesthetic, and this attitude of, “Alright, we just have to make it work, just put that machine together, duct-tape it, nail something in there, make it move because we have to keep going.”

MJ: Your drawings are particularly striking. They’re terrifying. Do you start with the drawings, or what’s your creative process?

WM: In most cases I start off with a sketch. But I’m also thinking about real images: out of National Geographic, out of fashion magazines, out of The Economist, out of Time. I’m making a sketch, but I’m using the existing images that have been put out in the world. I love magazines because they’re so dispensable, and they’re so quickly consumed. In that way they’re quite honest. They’re unashamed about how small an amount of time they’re trying to keep our attention. They’re the fecal matter of culture. If you want to find out what’s really is going on in the digestive system, you look at what’s coming out of it. They’re this cross-section of our gut. And there’s a lot shit in there!

MJ: Many of the figures in A Fantastic Journey are poised atop one another. Their sizes and juxtapositions suggest a power dynamic at work. Can you talk about that?

WM: I have this amateur side attraction to, and interest in, the sciences and biology and physics and evolution. Paleontology is of interest to me. I’m interested in the way these fields have helped us understand how we are human and why we are human. I’m also from the area that is considered to be the cradle of mankind.

We became Homo sapiens not that long ago, from the scientific perspective, and we’ve retained a lot of our beast nature. We’ve done all these amazing things in terms of our knowledge base and technology, and now we’re flying around and using the internet. But we’re still very animalistic. So, I think about hierarchies. I think about evolution. I think about how we stack up, how we sit on top of each other. How we pray that we know what we’re up to.

“Misguided Little Unforgivable Hierarchies” is a piece that I did around the time that I was very frustrated and angry with the fact that the US, where I live, had decided to pull itself into another war. I was really angry. There are a lot of explosions in my work: They look like blood spurts, but also, from a distance, like blossoms. A lot of my work shows these humanoid, animal-type creatures sitting/standing on top of each other, like the caste systems that we have. As much as we talk about democracy and freedom, we still have no problem mistreating and devaluing people.

MJ: Have you found the art world in New York City to be tainted by consumerism?

WM: Everything is deeply affected by the dominant culture. Consumerism is huge in the US. This is by far the wealthiest [nation], but also the biggest consumer in the world. Which means that a lot of things get used, a lot of things get wasted, and a lot of things get churned out in ways that are wasteful.

I’m not a policy maker. I’m not even a very great activist. My main thing is to make things that speak for the culture that I live in. And luckily, for whatever reason, I’ve found people who are interested in living with and owning and existing around the DNA of my mind, which is my visual work. I’ve found collectors who are willing to put money down to live with my work. So I can’t criticize the whole mechanism. But I can criticize it as an artist, in spite of the fact that I benefit from it. And there are problems with it.

MJ: British colonialism in Africa has been a big theme in your work. What about American neo-colonialism?

WM: A lot of my work reflects the incredible influence that America has had on contemporary African culture. Some of it’s insidious, some of it’s innocuous, some of it’s invisible. It’s there.

Photography is that thing that the explorer, the traveler, the tourist, the voyeur uses to figure out where the hell they’re going and what the landscape is all about. But a photographer also makes decisions about how people are seen without asking, “Is this really you guys? Is this what represents you?”

There are many ways to describe how Africa has been colonized and modified and packaged and branded by the West, by Europe, and certainly by America. The image of Africa is much more abstract and problematic in America.

What is Africa, anyway? Even I don’t know what Africa is, entirely. But I know that it’s not some of these simplified sound bites you hear in America.

MJ: Women warriers figure prominently in your work. What contemporary political or social figures do you view as warrior women?

WM: I love Arundhati Roy‘s work. Wangari Maathai is one of my biggest heroes. She used the replanting of trees as a way to empower women to take control of their environment. She was amazing. And, honestly, my grandmother. She is 93 years old. She has proven to be one of my heroes, one of my warrior women.