Doing "seg time" at a juvenile detention center in South Bend, Indiana, 2010.Richard Ross

“An art show that does more than jerk off…”

That was the subject line of an email I got about a current exhibit at Crane Arts in Philadelphia. Hardly publicist-speak. But Richard Ross is no publicist. He’s a talented photographer whose career has come to focus on the plight of incarcerated kids, and he recently went so far as to step into the shoes of his subjects for 24 hours. The things he’s seen in the course of his artistic mission have made him an activist, and led him to create Juvenile in Justice, a multimedia project “to visualize the American juvenile justice system.”

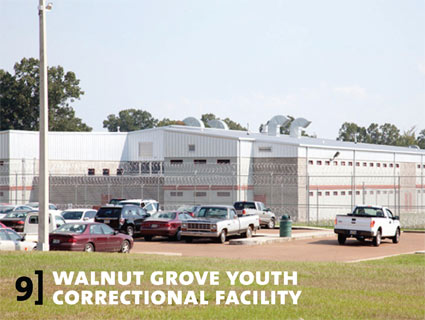

Like any artist, Ross is interested in having lots of people experience his work. The Juvenile in Justice show includes 75 of his stunning and challenging photographs shot inside youth prison facilities all over America, along with a full-scale reproduction of a juvenile solitary cell based on one of his photographs. The exhibit also features dozens of works from painter Mat Tomezsko and “ghetto potter” Roberto Lugo—whose unusual creations look like something you might find at your grammy’s house—if Grammy were a gangbanger.

But what really excites Ross, and what makes the exhibit unique, is what’s in it for the kids. On December 3, a host of volunteer lawyers will descend on Crane Arts to help local juveniles, and adults who committed crimes as children, clear their records so that they might get a fair shake going forward. Philadelphia Lawyers for Social Equity and the Defender Association of Philadelphia, the two groups providing the volunteers, hope to assist more than 150 people.

The process of purging (or sealing) the record of someone’s arrest, indictment, or juvenile delinquency proceedings is called expungement, and it’s next to impossible for anyone who can’t afford a lawyer. The rules are complex and vary tremendously by state. Most states allow the expungement of misdemeanors, and felony charges that don’t result in a conviction. A few allow certain felony convictions to be expunged, but only after a substantial waiting period. And then there are states like Alabama (and the federal government, for that matter) that offer no expungement at all.

“It’s there for the rest of your life,” says Ryan Allen Hancock, a cofounder of Philadelphia Lawyers for Social Equity. “It means they may never work again, ever. They may never have access to public benefits, get housing, teach. There are literally thousands of what we call collateral consequences”—loss of societal privileges as the result of criminal penalties.

Whatever you might think of former criminals, that’s just terrible public policy. It stacks the deck against people who aspire to get past their mistakes and try and live a decent life. “What happens when you don’t allow people gainful employment? What option does that leave them?” Hancock says. “This is not about forgiving people. We need to ask if our policies are perpetuating the effects that we want, and I don’t think they are.”

The fact is, Hancock says, “95 percent of guilty verdicts in state systems are plea agreements, and the majority of those people never spend a day in jail. Little do they know that that plea agreement may forever bar you from a job. The state doesn’t believe you are bad enough to incarcerate, but you’ll forever be pushed out of public housing and benefits.”

Over the past two and a half years, Hancock’s group has filed more than 3,000 expungement petitions, most of them successful, for people who can’t afford a lawyer. Unlike a pardon, expungement allows a former offender to legally deny that he was ever arrested or charged with the crime in question so long as he was found not guilty, got the conviction dismissed, or—in the case of certain crimes, such as drug use or DUI—completed a post-conviction rehabilitative program. But most adult felony convictions cannot be expunged. Juveniles get a break because their convictions, administratively speaking, are not true convictions—unless they are tried as an adult.

Even so, few juveniles bother to get their records sealed. But it’s important that they do, Hancock says. In Pennsylvania, for instance, many juvenile court records are publicly available. That can affect a person’s employability and immigration status, or the ability to get a driver’s license, find housing, or even enlist in the military.

The problem is particularly pronounced in Pennsylvania, Hancock says, because the Administrative Office of Pennsylvania Courts puts its records, including many juvenile court records, online and sells the data to private brokers, who in turn sell it to employers. It is a crime for an employer to discriminate against an applicant who has been charged and found not guilty of an offense, but that’s nearly impossible to enforce. The entire issue “is really about the collection and dissemination of data and its impacts,” Hancock says. “Why should nonconviction data be published? It can only be used for unlawful purposes, so why in the hell should they send it out?”

Hancock’s group holds monthly expungement clinics in downtrodden West Philly, as well as occasional one-off clinics—at black churches, for instance—but teaming up with artists is a first. “So often art that speaks to social justice issues is simply looked at, provoking brief contemplation,” Ross writes. “This exhibition turns the gallery into a laboratory for social change: Photographic evidence of a problem hangs on the walls, while the people among the art work to alleviate it.”

The Juvenile in Justice exhibit continues through December 12. Additional details here.