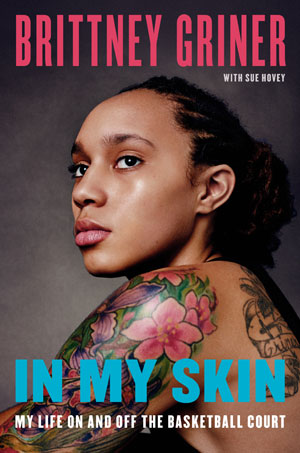

Brandon Sullivan Photography

Even if you don’t follow women’s basketball, you probably know of Brittney Griner and her nasty dunks. Last year, the 6-foot-8 Phoenix Mercury center made the WNBA All-Star Game as a rookie, and tied the league’s all-time dunk record with two slams in her very first game. But she’s more than one of the WNBA’s hottest stars. She’s also one of the most famous gay athletes in all of sports; last year, she became Nike’s first out endorsee, and she’s helped create an anti-bullying mobile app that’s currently raising money on IndieGogo. So why, at 23, did Griner feel the urge to write a memoir? (In My Skin, cowritten with Sue Hovey, was released in April.) It’s simple, she says: “I didn’t want to wait till the end of my career to tell my story.”

Mother Jones: You write that you were bullied as a kid, and that you felt like “a physical misfit, my body flat and thin, my voice low.” When did you start to feel comfortable in your skin?

Brittney Griner: I would say ninth grade, when I started wearing the clothes that I wanted to wear. I was so tired of living a lie, dressing a certain way. When you go to high school, you definitely feel like you’re an adult, and I wanted to be true to myself. By the time I got to college I was completely out, and all my friends knew—just about everyone in my family knew. That’s when I told myself, “Okay, I wanna do all this.”

MJ: You’re known for your style—lots of tattoos, but also the argyle socks, bow ties, preppy chic. How has that style evolved?

BG: When I first came out, I kinda overdid it. I dressed extremely older-boyish, like sagging, and big shirt and big jeans. I was just like, “I’m gonna go extreme.” And then as I got older, the baggy clothes got a little more fitting to my body, but still masculine. Before, I wouldn’t wear tight jeans—”That’s girl! I want guy!” I thought. But now I wear jeans that actually fit me and look good. A lot of people do the preppy look, and the bow ties and the vest and jacket, the blazer and everything, and I started to like it even more.

MJ: When the WNBA proposed tigther-cut uniforms, how did you react?

BG: I was just running in slow motion, saying, “Nooooooo!” I play basketball. I need a jersey and I need some shorts that I feel comfortable in. I’m trying to hoop, not go to a fashion show on the court. Short shorts are not for everybody. I’m not trying to wear capris, but I got a lot of leg. I need to cover it up a little bit. They want more male attendance, and for us to change our uniforms to “sleek and sexy” takes away from what we’re trying to do on the court. I want you to come watch my game, not the uniforms. If you wanna come just because we look sexy, then I really don’t want you there. I feel like we need to get away from that.

MJ: Your Nike contract allows you to model clothes branded for men. A Nike spokesman told ESPN the Magazine, “It’s safe to say we jumped at the opportunity to work with her because she breaks the mold.”

BG: I want to print that quote and put it on the wall! For a company like Nike to say that I’m breaking the mold! I was extremely happy. I’m not the only female that wears men’s clothes, so I’m not one in a million. But someone told me I was kinda pioneering it—for it to be okay, to be accepted.

MJ: You write at length about your struggles at Baylor, both with coach Kim Mulkey and with the school’s anti-homosexuality policy. What was it like to hear from folks in Waco that this was some sort of betrayal?

BG: It’s not right. Like the rule that Baylor has in the handbook, that if you’re openly gay you can be kicked out—it’s unjust, and I think it should be changed. I never had a problem with my team. My teammates accepted me. We were on the court, we played, we hooped, we fought for each other, and I had a great time as far as basketball. Nobody ever came up to me and was like, “Get off our campus.” I never got that. And people knew on campus. I wasn’t hiding. From the way I dressed to the way I acted in public, it wasn’t a problem, so I don’t understand why the rule is still there.

MJ: You write that you didn’t know about the policy before arriving at Baylor, and that Mulkey told you being gay wouldn’t be a problem there. And yet people ask, “Why did you go to Baylor if you knew it was anti-gay?”

BG: First off, it’s easy for people to say stuff when they don’t know the full story. If they would read the whole story, the whole book, they would see. I was told everything would be fine, and I didn’t know about the rule until later on. I get the question a lot: Do you wish you would’ve gone somewhere else? No, no I don’t. I went 40-0. I won a national championship. I grew as a person, I grew as a player, and me and Coach Mulkey, we had a lot of great times. She taught me a lot of great lessons, and I met a lot of great people. And I still go back to Baylor. I’ve been back up there; I went there for homecoming. I went down on the field and the fans clapped and cheered for me, yelled my name. I love my school; that’s always going to be my school. People who think, “Oh, she should’ve just gone somewhere else”; I’m like, “No, I was where I needed to be.”

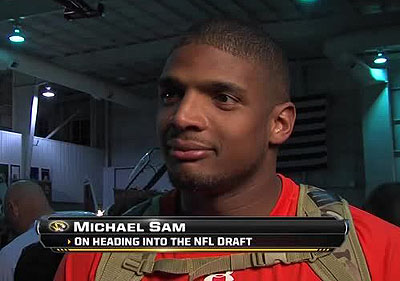

MJ: What do you make of the high-profile comings-out of Jason Collins, Michael Sam, and Derrick Gordon?

BG: I had a prior agreement with ESPN to come out with them, but it kind of came out earlier in a Sports Illustrated online interview. It was fine. I wanted it to be a conversation. I didn’t want it to be like, “Breaking news: Brittney Griner is gay!” I just wanted it to be on my time. It’s a little bit tougher on the male side—people judge really hard—and when they come out it’s definitely big news. It takes a lot of bravery. I would love for it to get to the point where it’s not breaking news, not how they define us. We don’t want to be treated any different.

MJ: Not to shift gears too quickly, but do you think should college athletes get paid?

BG: I do. You give up a lot of your time. You have your not-mandatory-but-mandatory summer. “You don’t have to be here, but you better be here.” We miss holidays, we miss all that. We devote all our time to basketball. Studying on the road, late nights, getting in—it’s like we’re working a job nonstop. And I definitely think we should get a little bit more.

MJ: How would it have been different if you’d been considered an employee?

BG: An employee. [Pauses.] I think I would like “employee,” because that means that I’m on that payroll! [Laughs.] Honestly, that’s how I feel. I felt like I was a Baylor employee. Instead of going to work in the office and punching in on the timecard, I was going to practice everyday, right after class got dressed, and got in practice for a couple of hours. Summertime, I was there the whole time. But we don’t get any off days. We can’t call in sick.