FIFA President Sepp BlatterAlessandro Della Bella/AP

When the FIFA World Cup opens today in Sao Paulo, the eyes of the world will be glued to the action on the field—but recent developments off the pitch are threatening to steal the spotlight. From the news of strikes and protests coming out of Brazil to the shadiness surrounding the awarding of the 2022 Cup to Qatar, it’s difficult to keep all of the scandals straight. But fear not: Check this cheat sheet to get a sense of the off-field stories that’ll be dominating conversations for the next month.

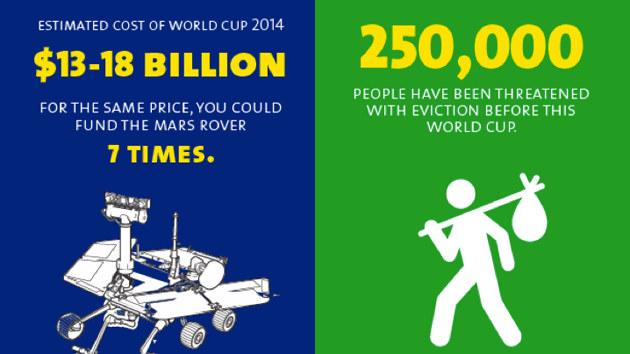

Brazilians are really, really mad. Over the course of the past few years, Brazilians have grown outraged at the government’s handling of the World Cup. Even in this soccer-obsessed country, people are deeply resentful of the government’s decision to spend as much as $14 billion on the Cup while millions of its citizens lack basic services—services the government promised to improve ahead of the Cup. On top of that, at least nine workers have been killed in accidents related to rushed World Cup construction projects; activists are alleging that more than 250,000 people faced eviction threats to accommodate Cup construction and preparations; and the presence of brand-new Cup buildings has raised rent in working-class neighborhoods, pricing longtime residents out.

The streets of Brazil’s major cities have become chaotic battle zones. Tens of thousands, from the homeless to workers, have poured into the streets over the past few months to protest the government’s handling of the Cup and riot police have responded with rubber bullets and tear gas. A series of strikes by public-sector workers demanding higher wages has paralyzed Brazil’s largest cities, bringing yet more protesters and police into the streets. Subway workers are the latest to strike, inspired by previously successful efforts by bus drivers and federal police, who threatened to strike. On Tuesday, subway employees went back to work after five days of striking, but threatened to resume the strike pending a vote (Update, 1:28 ET: no subway strike, but Rio de Janeiro airport workers have begun a 24-hour stoppage). Sao Paulo, host of Thursday’s opener, is famous for its hundred–mile traffic jams, but strikes last week brought the city to a near stand–still. A scrimmage between the US and Belgium, planned for today, was called off due to the gridlock. As thousands of visitors descend on the city, another strike has the potential to disrupt official World Cup events.

And the stadiums, airports, and transport systems aren’t even finished. Although World Cup action starts today, and an estimated 600,000 visitors have begun to descend on Brazil, up–to–date reports indicate that the infrastructure still isn’t ready. Here’s a brief list of what remains unfinished:

- The stadiums. Sao Paulo’s Arena Corinthians, which will host today’s opener between Brazil and Croatia, was supposed to be completed last year. But the roof is unfinished, and 20,000 fans will sit in seats that the Daily Mail alleged wouldn’t pass a UK safety test. In Manaus, deep in the Amazon, the stadium remains unfinished and the field is in horrible shape ahead of Saturday’s game there.

- The airports. Several airports around Brazil are still not ready to handle the thousands of flights that’ll come in and out over the next weeks. In Manaus, workers, scaffolding, and machinery are everywhere. In Belo Horizonte, there are muddy sidewalks, an unfinished food court and dust everywhere. Brazil’s Folha de Sao Paulo found that the airports of Brasilia and Sao Paulo were the only ones ready to handle the traffic.

- The transit. In selling the Cup to the people, Brazilian officials promised 35 new rail projects—today, just five are complete. Visitors may have to resort to overcrowded roads to get to games. The rushed and haphazard construction of transit projects has also had an enormous human cost: on Monday, a worker was killed while working on Sao Paulo’s monorail. The still–unfinished prestige project was supposed to have been completed well before the Cup.

Across the board, it’s a mess of bad PR for Brazil, and Brazilians are worried that their country’s time in the world’s spotlight could become a historic embarrassment. President Dilma Rousseff’s approval ratings have slid to 34 percent, and it’s not a stretch at all to suggest that the success of this World Cup—even the on-field success of the Brazilian team—could influence her impending re-election campaign.

Bribery, corruption, and worker abuse have reached a boiling point in Qatar, the 2022 World Cup host. The world was shocked when Qatar won the bid to host the 2022 World Cup in 2010. Of course, there’s the weather: the Persian Gulf state suffers temperatures well north of 100 degrees—sometimes over 120—in the World Cup months of June and July. And there’s the fact that the tiny, oil-rich nation has little soccer history or presence on the sport’s international stage: It’s never sent a team to the Cup to compete.

Turns out, there may have been more suspicious factors behind FIFA’s bizarre decision. The British press have alleged that Qatari billionaire Mohamed bin Hammam paid off FIFA officials in order to secure their votes to bring the Cup to his country. Emails obtained by the Sunday Times suggest that Qatar and 2018 World Cup host Russia cooperated to help each other win bids, and that bin Hammam used his connections in business and government to bribe officials from Thailand to Germany. If the allegations are true, FIFA Vice President Jim Boyce said he’d push to strip Qatar of the Cup and re-award it to another country.

Another worry, especially for fans, is the cultural conservatism of Qatar. Gay fans have expressed concern about visiting the country, where homosexuality is illegal, and foreigners have been whipped and deported for violation. In 2010, FIFA President Sepp Blatter made headlines by suggesting that gays “should refrain from sexual activity” if they visit Qatar. He quickly apologized.

What could push all this to critical mass is ongoing outrage over Qatar’s mistreatment of the construction workers tasked with building Cup infrastructure. The long hours of hard labor in unbearably hot conditions have proven lethal: It’s estimated that 1,200 workers have died in Qatar since the country was awarded the Cup. They are almost exclusively migrant workers from South and Southeast Asia and can only leave Qatar with the written permission of their employers—a system some watchers have compared to slavery.

Five of the World Cup’s six top corporate sponsors (including Coca-Cola and Adidas) have voiced concern over corruption and worker abuse allegations, and publicly back formal investigations. Blatter, in a rare off-message moment, admitted that giving Qatar the bid was a “mistake.” Qatari officials have denied wrongdoing on corruption charges and promised to reform labor laws—but clearly, they have a lot more to worry about than air-conditioning their stadiums.

There was match fixing at the 2010 World Cup events in South Africa. While World Cups’ present and future are beset with trouble, the 2010 Cup in South Africa was widely considered a success and a model for future hosts to follow. That legacy may soon be tarnished, if only slightly: Reports have surfaced that pre-cup exhibition matches in South Africa were fixed. A New York Times investigation alleges that powerful gambling interests paid off referees to manipulate the outcomes of certain games. At least five games, and possibly as many as 15, were targeted. While the referees giving out questionable handball calls and yellow cards are clearly to blame, FIFA concluded that some South African soccer officials probably helped to some extent.

If true, this scandal would cast doubt on South Africa’s World Cup legacy. But there are implications for this year’s event, too. It proves that match-fixing—a persistent evil in soccer—is alive and well, and not even the World Cup is immune. Billions are wagered on the Cup worldwide—over $1.6 billion will be wagered in Great Britain alone—and there are powerful interests seeking to manipulate outcomes. FIFA dragged its feet for years on the South Africa investigations, calling into question its ability to prevent match-fixing in Brazil, which officials publicly say is a risk.

A uniting thread in all of these scandals. FIFA looks really, really bad. There’s evidence to argue that the overlords of international soccer are corrupt and incompetent; at best, they’re merely incompetent. Between insisting that Brazil and Qatar will be successes as planned and accusing World Cup critics of racism, FIFA looks plain ugly. Not convinced? Watch John Oliver’s brilliant explanation:

So, while the implications of these controversies are big for Qatar and Brazil, they’re big for FIFA, too. Some are arguing to get rid of it altogether. How the upcoming months unfold could determine President Blatter’s viability going forward. A group of prominent European soccer executives have called on the longtime president to step down. For the health and well-being of soccer and the countries that love it, that might not be a horrible thing.