Jovan Belcher, shown here in 2011, killed his wife then himself in 2012. Researchers determined he suffered from CTE.Jacob Paulsen/ZUMA

Yesterday, the country’s leading investigators of sports-related brain injuries released what could be their most shocking finding yet: Of the 79 deceased NFL players examined, 76 showed evidence of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE. The researchers at the Boston University CTE Center have examined, in total, the brains of 128 people who played football at all levels—from high school to the pros—and 101 showed evidence of CTE. The numbers buttress a growing body of evidence that suggests that playing football at any level can lead to grave health consequences.

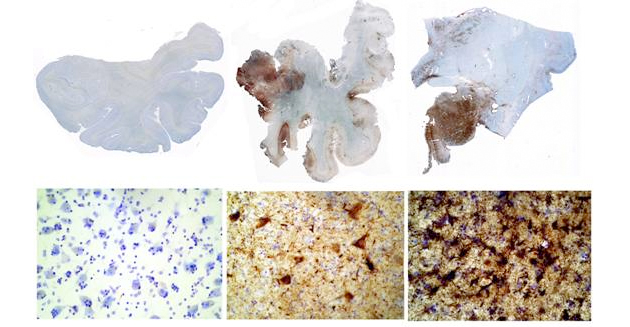

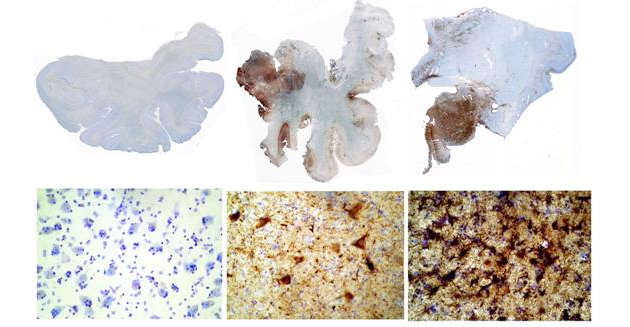

In case you haven’t been following the story, here’s how CTE works: When the brain is subjected to repeated trauma—from the severe (and rare) concussion-causing hits to the repetitive, smaller impacts a lineman might absorb thousands of times in his career—its tissue starts to deteriorate. That causes the buildup of abnormal tau proteins, which interfere with a whole host of critical brain functions. In the short term, it can lead to memory loss and impaired judgment; in the long term, it can lead to severe depression and dementia. Ex-players describe its symptoms as crushing, and in many cases, the pain, unpredictable outbursts of rage, and memory loss becomes too much to bear.

In the past few years, several former NFL players have committed suicide and were later found to have had CTE. On Monday, researchers found that Jovan Belcher—the Kansas City Chiefs linebacker who killed his girlfriend and himself in 2012—also had been suffering from CTE.

Two decades ago, when players began to link their health problems with their football careers, the NFL denied the prevalence and severity of brain injuries. In the 2000s, the league’s (now-defunct, and poorly named) Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Committee frequently stated that not one NFL player suffered from chronic brain damage. In 2009, years after the first player had been diagnosed with CTE, Dr. Ann McKee—a leading Boston University researcher—presented her findings before an NFL committee, which reportedly attacked the scientific rigor of her research. Meanwhile, right-wing media like Breitbart have been downplaying CTE and attacking doctors’ credibility for years, often referring to their work as “junk science.”

Currently, there’s no way to definitively know if a living player has CTE. (Traumatic brain injury, which may lead to CTE, can be identified in living people.) Leading researchers are the first to point out that their sample population is skewed: Brain bank donations come disproportionately from players who suspected they had CTE while alive. CTE sufferers who commit suicide have tended to shoot themselves in the chest; in some cases, they’ve left notes asking that their brains be used for research.

Still, the more CTE researchers study players’ brains, the grimmer the findings get. While they admit the shortcomings of their research, CTE experts overwhelmingly insist that football increases risk of traumatic brain injury. The outcry has pushed the NFL to backpedal on its previous position: It recently opted to settle in a massive class action suit filed by former players suffering from CTE-like symptoms. It will likely pay out hundreds of millions of dollars, if not more. An internal study commissioned by the NFL found that 30 percent of players will develop brain trauma complications sooner, and more frequently, than the general population. (The league didn’t dispute the findings.)

Just how the developing research will affect other levels of football remains to be seen. The hit sustained by University of Michigan quarterback Shane Morris last weekend—and coach Brady Hoke’s decision to let him keep playing—was shocking.

We know the NFL has a brain injury problem. Given the outcry over what happened to Morris—and the $70 million concussion settlement the NCAA reached in July—it’s obvious that college football does too.