In what’s become an annual tradition, we invited Mother Jones staffers to write up their favorite books published this year, the ones they’d recommend to friends and relations, and so here they are. We can’t read it all, of course—feel free to list your own favorites in the comments. Foodies should be sure and check out food and ag writer Tom Philpott’s “Best Food Books of 2014.” For music lovers, MoJo critic Jon Young has shared his list of “The 10 Best Albums of 2014.” Stay tuned for more great end-of-year coverage from the MoJo crew.

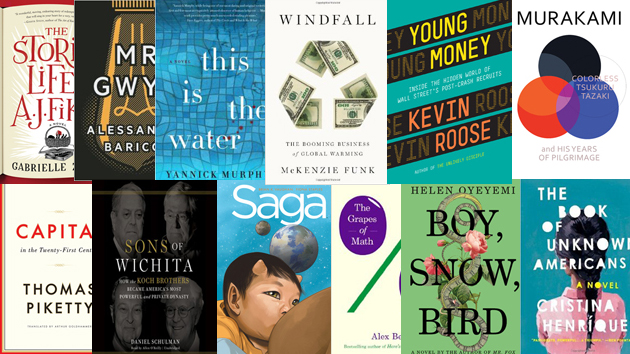

Capital in the 21st Century, by Thomas Picketty: You read a half-dozen reviews, but that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t crack the French economist’s vast tome. In prose as sparkling as a gold coin, he crunches centuries of data to demonstrate capitalism’s tendency to concentrate wealth in the hands of a few, unless checked by determined state intervention. Along the way, he strews plenty of gems—on why post-World War I novelists stopped mentioning prices in their books (inflation), the contribution of slavery to America’s economic emergence (huge), and more. In all, a bravura performance from that rarest of commodities: the rock-star economist. —Tom Philpott, food and agriculture correspondent

The Grapes of Math, by Alex Bellos: A readable, fascinating exploration of some higher math that I haven’t thought about since the dark days of high school trig and calc. There is a lot of cool stuff for the math-curious in here (Benford’s Law, Conway’s Game of Life, how to fairly divide a cake between three people) presented in a lively manner not seen in the old math textbooks. Still, if you never want to see an equation again, this book may not be for you. —Dave Gilson, senior editor

The Book of Unknown Americans, by Cristina Henríquez: While often lumped together as a monotone immigrant workforce, the “unknown Americans” in Henríquez’s novel assert themselves as a messy web of distinctive voices sharing a drab apartment building in Delaware. There’s Quisqueya, a nosy Venezuelan with a closely guarded past; Nelia, bent on becoming the next Rita Moreno; Benny, who got into drugs after leaving Nicaragua. At the novel’s core are the Riveras, who’ve come to America from Mexico because their daughter, Maribel, can’t fully recover from a brain injury. Wracked by guilt but determined to make do, her mother navigates convenience-store grocery shopping, bus routes, and English, with its “hard letters, like miniature walls.” When Maribel catches the eye of a neighbor, two families come crashing together with an unexpected twist. Though Panamanians, Paraguayans, Mexicans, and Boricuas take center stage, Henríquez’s tale, spun with simple, throat-tightening prose, will appeal to anyone who’s had to adapt to a strange new place. —Maddie Oatman, research editor

Sons of Wichita, by Daniel Schulman: If you had hundreds of millions of dollars, you’d think, life would go smoothly. Not so for the Koch brothers. In this gripping soap-operatic tale of money, power, and family dysfunction (excerpt here), Daniel Schulman, a senior editor of this magazine, chronicles the rise of the four sons of Midwestern industrialist Fred Koch. It’s a real-life mashup of Dallas and Dynasty, with the four Kochs fighting (physically!) and suing each other over the decades, as they vie for control of the expanding family empire. The arch-conservative, anti-government passions of Charles and David don’t dominate the story until various scores are settled. Then Schulman details how C&D go from being supporters of a fringe political party to becoming the most influential fat cats of the day. A product of extensive investigative digging, Sons of Wichita is a balanced, gracefully penned, and fascinating inside look at a small but oh-so-significant slice of the American elite. —David Corn, Washington bureau chief

Boy Snow Bird, by Helen Oyeyemi: Boy Snow Bird is a retelling of Snow White, a fairy tale made (somewhat) modern. But it’s much more than that: Oyeyemi’s tale takes us from a rat-catcher’s den to a bucolic upstate town in a matter of pages, and it upends the senses in a way you won’t want me to reveal here. With a tangle of love, family, and history, Oyeyemi challenges the very notion that we understand who is in front of us. It’s as if she’s holding up a mirror to have us look for what we thought was left behind. —Elizabeth Gettelman, public affairs director

The Signature of All Things, by Elizabeth Gilbert: (Note: The paperback was published in 2014; the hardcover came out last year.) No one loves Liz Gilbert’s latest protagonist Alma Whittaker, but that’s the point: Her true love is knowledge, all kinds, but particularly mosses. In The Signature of All Things, Alma is the smartest woman in a swath of history—late 1700s new America. The New York Times called her a “large, spinstery botanist,” and there’s perhaps too much ink given to how plain and unlovable she is. But the reader gets to know and care for her, from her complicated family ties to her unrequited love to her beating Charles Darwin to divining natural selection (but failing to publish). Every flowerly detail is so precise, and the period and its subtleties are so well researched, it’s as if Gilbert (read our interview with her here) has unearthed an 18th-century autobiography. The airy delight that was Eat, Pray, Love this isn’t; but it’s glorious in its heft. —E.G.

This Is the Water, Yanick Murphy: This literary thriller had me smelling the chlorine that permeated my youth as an age-group-competitive swimmer. At heart, it’s a serial killer novel whose villain stalks his victims from the pool bleachers. But Yanick Murphy isn’t a crime novelist. Her works have won Pushcart and PEN prizes and she writes for McSweeney’s, so This Is the Water isn’t just a good airplane read. Written in the second person, it’s unusual and quirky, as is the setting, which the main character, whose daughters work out there, simply calls “the facility.” Murphy gets almost all of the tiny details of competitive swimming just right—which endeared her to me from the beginning. The criminal aspect is a backdrop to a story about failing marriages, infidelity, obsessive parenting, the mindset of a killer, and of course, swim-meet intrigue—all of which appealed to me as a crime-novel junkie and swimmer. But the novel’s oddities and Murphy’s hauntingly lovely writing will hold plenty of appeal for a broader audience. —Stephanie Mencimer, reporter

Windfall, by MacKenzie Funk: If you read one book about climate change this year—no, ever!—this is it. An exceptional crafter of narrative, Funk travels the globe hanging out with fascinating characters who have one thing in common—they are all angling to turn global warming to their advantage, financially or otherwise. Forget the deniers. They’re idiots. Funk follows the money, and the result makes for some fabulous and enlightening reading. Here’s an abbreviated taste. —Michael Mechanic, Senior Editor

The Storied Life of AJ Fikry, by Gabrielle Zevin: A delightful story about a curmudgeonly, widowed, deeply unhappy bookseller on a touristy East Coast island whose life is upended by the theft of a rare tome—his nest egg—and the sudden appearance, not long after, of a person who gives his life new meaning. (No, I’m not going to give it away.) Author Gabrielle Zevin’s engrossing cast of small-town characters make Fikry difficult to put down. —M.M.

Being Mortal, by Atul Gawande: If you care about living and dying with dignity, this latest book from the wonderfully talented author/surgeon Atul Gawande will be the most important thing you—and your aging parents—read all year. Being Mortal confronts the failure of the medical community to grasp the difference between caring for the elderly and treating them, usually futilely. Sounds grim, and sometimes it is. (You’ll find more details on the content here, plus my interview with Gawande.) At the same time, it’s a great read that leaves you better equipped to face the future, and without making you feel like you just took your medicine. —M.M.

Mr. Gwyn, by Alessandro Baricco: I judged this book at first by its elegant cover, and a good thing, too, for within it was a story (plus Three Times at Dawn, a story within the story) that’s truly unique. The titular Jasper Gwyn, a famous author, abruptly decides to quit writing books. Over time, he develops a new sort of discipline—he calls himself a “copyist”— writing meticulous portraits of people who pose for him as a model would for an artist. What he writes are not profiles, but rather stories that manage to encapsulate the soul of the individual—we see Gwyn’s first subject, his agent’s overweight and self-conscious assistant, bloom under this strange treatment. Baricco’s characters are enigmatic and his story enticingly mysterious. Bonus: You’ll learn more than you knew existed about artisan lightbulbs. —M.M.

Young Money, by Kevin Roose: In what you might call an Occupy-era addendum to Michael Lewis’ Liar’s Poker, financial journalist Kevin Roose embeds with a bunch of Wall Street newbies struggling to claw their way up the ladder. The book is enlightening, thought-provoking, and—Oh. My. Fucking. God.—totally appalling! When Roose crashes an actual fraternity of Wall Street CEOs and hedge fund douches, it’s like a scene out of a bad movie—only real, and therefore pretty great. Would that every journo had that kind of chutzpah. —M.M.

Saga Deluxe Edition, Vol. 1, by Brian K. Vaughn and Fiona Staples: Saga is a comic-book series that follows two star-crossed lovers as they flee a ceaseless interplanetary war to protect their young daughter. It’s also a closely observed story about a couple fiercely in love, and the unique forms of generosity and cruelty that people in love can visit upon one another. It’s tough to imagine anyone besides master storyteller Brian K. Vaughn achieving a balance between these two themes. But in his hands, the result is a wry, witty, and tender adventure story, punctuated by cliffhangers. Saga is not for squeamish readers. Fight sequences are strewn with teeth, guts, and bone shards. The scuzzier characters frequent a brothel planet. (Picture an X-rated version of the Mos Eisley cantina.) But readers with fortitude will love Saga for its arch dialogue, exhilarating plot, and, above all, exquisite art: Fiona Staples imagines alien races of soldiers, journalists, bounty hunters, and baby nannies with staggering visual inventiveness. There are nights when I pull Saga off the shelf just to stare at it. —Molly Redden, reporter

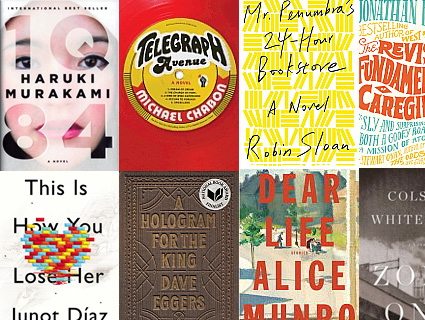

Colorless Tsukuro Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage, by Haruki Murakami (translated by Philip Gabriel): Full disclosure: This was my first Haruki Murakami novel, and I figured this regretful fact would make my reading labored and challenging. Instead, I dove easily into the book, which follows the travails of protagonist Tsukuro Tazaki after he leaves his hometown for Tokyo and is banished from his closest friends for reasons unbeknownst to him. The story is rooted in the intense dread and sadness Tsukuro feels as a result of his rejection, a painfully universal experience, and reading it has sparked my interest in the rest of his oeuvre. —Mitchell Grummon, business analyst