<a href="https://www.flickr.com/photos/statefarm/8476682346/in/photolist-8KN5N5-dV4dkC-cE2ktW-cE2kx3-cE2kBJ-dPnNZk-pVb8Yy-4vghwU-iM923z-8nXY9f-nZMzm6-74XAB7">State Farm</a>/Flickr

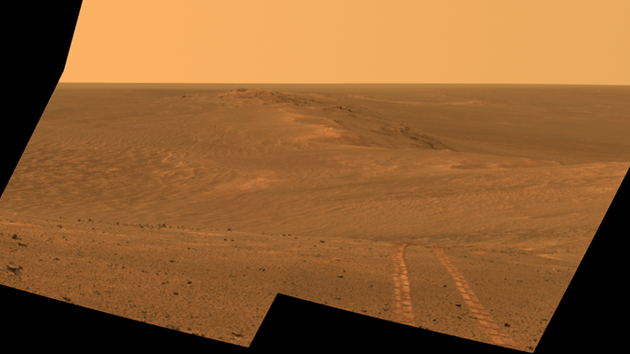

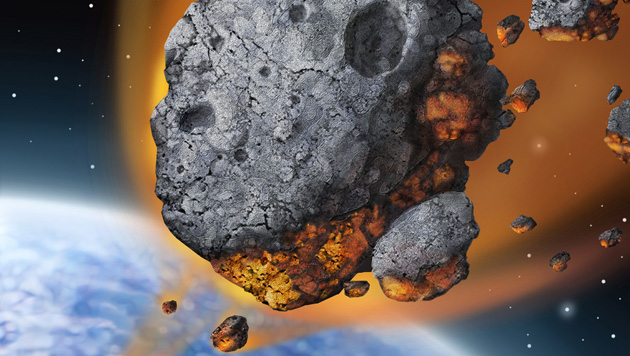

Neal Stephenson’s latest novel, Seveneves, could have been titled Goodnight Moon, Forever—the latter blows up in the book’s very first sentence. It’s not long before a charismatic scientist (who vaguely resembles Neil deGrasse Tyson) realizes the catastrophic implications: Within two years, moon chunks will rain from the sky, obliterating everything on the Earth’s surface.

Seveneves depicts humanity’s effort to get as many people as possible into space before that happens—and everything that follows in the next 5,000 years. Over 867 pages, Stephenson blends astrophysics, genetic engineering, robotics, psychology, and geopolitics into an epic narrative.

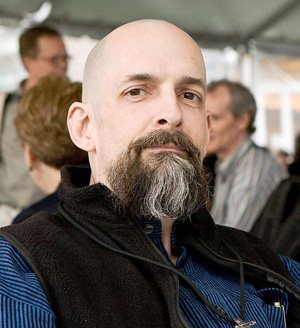

The novel’s vast scope won’t come as a surprise to Stephenson’s fans. He is perhaps best known for 1992’s Snow Crash, a virtual reality tale set both online and in an anarcho-capitalist future version of Los Angeles, where it follows the adventures of a sword-wielding hacker (Hiro Protagonist!) and a teenage skate courier. (It was Snow Crash that popularized the word “avatar.”) A subsequent book, The Diamond Age, revolved around the future of nanotechnology. Cryptonomicon, published in 1999, wove its way through the history of computers and cryptography, while the three-volume Baroque Cycle (written with a fountain pen) delved into the wars, intrigue, and technological innovations of 17th Century Europe.

Stephenson’s seeming ability to envision things yet to come in various realms has won him consulting jobs in addition to readers. In 2006, when he started cooking up the plot of Seveneves, he was working at Blue Origin, the Jeff Bezos-owned space company that launched a rocket this month. He currently holds the title of “chief futurist” for Magic Leap, a company that aims to create a virtual reality framework as convincing as the one in Snow Crash. I called Stephenson at his Seattle home base to talk about space junk, sci-fi tropes, and why it’s time we got over Blade Runner.

Mother Jones: If the moon really blew up, what would you do first?

Neal Stephenson: Well, since I’m geeky and I know lots of geeks, I would probably look for ways to make myself useful in some kind of technology effort. I can also see myself trying to tell stories that could be read by people in the distant future.

MJ: Where did the idea for Seveneves come from?

NS: I’d been reading some papers about space junk, which is just pieces of dead satellites and rocket boosters and so on that are permanently in orbit around the Earth. They pose a hazard, because the more pieces of junk are up there, the greater the chance that they’re gonna smack into a station with a person in it, or a valuable satellite. There’s kind of a doomsday scenario where a chain reaction occurs and so many pieces of debris get created that it becomes basically impossible to go into space. So I thought that was an interesting scenario. Then I came up with the idea of having the moon be the thing that would start the chain reaction, and just having it be a disaster on a much bigger scale.

MJ: Did the book require a lot of research?

NS: Embarrassingly, I knew an awful lot of it, because I have been just a hopeless space geek since before I could walk. It was almost a matter of forcibly not putting too much into the book. In the case of the International Space Station, you could easily gather vast amounts of information about how that thing works and what it’s like to live aboard it and how you eat, how you go to the bathroom, etc. I had to make a decision pretty early that I wasn’t gonna go there. I suspect if you were an astronaut who actually lived there, you’d feel like a lot was left out.

MJ: Do you think you might hear from them?

NS: By and large, I don’t think astronauts are complainers. In general, when knowledgeable people see things they know about depicted in fiction, they tend to be happy that somebody’s paying attention to what they do. It’s largely a matter of respect; you don’t want it to seem as though you just didn’t put out any effort.

MJ: What did you think about Blue Origin’s rocket launch?

NS: Building rockets and operating them is just ludicrously difficult. There’s a reason why the Soviet Union and the United States competed during the Cold War in the propaganda realm by launching rockets. You have to bring together so many different scientific and engineering disciplines and kinds of operational skill that it’s really only achievable by a very small number of organizations. You can intellectually know that, but you don’t fully know just how many things can go wrong until you see it up close. So anytime I see a Blue Origin or a SpaceX actually launch a rocket, even if there’s a glitch—both Blue Origin and SpaceX were not able to land their boosters as they had hoped, but even coming close would be an amazing achievement.

MJ: A few years ago, you wrote about “the general failure of our society to get big things done“—the idea that we’ve become too afraid of taking innovative risks. Do these companies and their projects alleviate your concern?

NS: Yeah, actually. I think that the stable of companies Elon Musk has put together is a clear counterexample to that. I’d like to see more of it. We’ve got big infrastructure problems. We’ve been kind of living off of our patrimony, you know? We’ve got the same set of railroads and interstates and power plants that was built by a previous generation, and if we’re gonna maintain a healthy economy that works for people, we need to get back into the habit of building things like that.

MJ: Should that be the government’s job?

NS: Some of them really can only be done by governments. Like, Elon Musk wants to build the Hyperloop between LA and San Francisco. You can’t get the right of way for something like that unless you’re working pretty closely with the government. It’s a vexed question in the United States now, because the idea of government has become kind of a political football.

MJ: Is the failure to get big things done something science fiction can address?

NS: I guess I’d turn it around and say that if you’re a science-fiction writer, that’s the only tool you’ve got. It may actually be useful—or useless. I think you can make an argument that there is a practical value in a more optimist kind of science fiction, and that’s sort of the basis for the Hieroglyph anthology we published last year. The argument there is that a lot of times people who want to build a new thing can sort of rally around visionary science fiction and say, “This expresses the vision of what we’re trying to build.”

MJ: What about pessimist science fiction? Snow Crash is often described as dystopian.

NS: Snow Crash obviously has dystopian aspects. That’s the thing that kind of pokes you in the eye when you read the book. I actually don’t think it’s quite as dystopian as people consider it. There’s a statement pretty early that the modern economy has kind of spread everything out into “a broad global layer of what a Pakistani bricklayer would consider prosperity.” So depending on where you’re coming from, that could be a good thing or a bad thing. The Pakistani bricklayer might actually think that’s a pretty good deal.

I think that there was a broad move in science fiction—and I personally became aware of it with the movie Alien—where the ship is kind of dingy and beat up. These are blue-collar people working for a company that is kind of sinister. It was very cool. It created a sense of realism and immediacy that was lacking in some of the old Star Trek-y kinds of science fiction, and it became the standard way of doing it. Certainly it made Star Trek seem sort of campy and naïve.

Also, if you’re making a movie, it’s just easier and cheaper to take an existing landscape and beat it up than it is to invent a new landscape. The classic example is the Statue of Liberty falling over and lying in the sand at the end of Planet of the Apes. That, from a just purely commercial standpoint, is enormous bang for the buck. It told a whole story about the fall of civilization with a very inexpensive special effect. Whereas when James Cameron did Avatar, he spent an enormous amount of money designing an alternate world from scratch. So the dystopian style has become the default just for economic reasons. But I sense that people are now getting tired of it, and kind of rolling their eyes every time another grim dystopian movie or TV show hits the media scene.

MJ: So why do these movies and shows keep coming?

NS: Within the world of people who write science fiction literature, everything I’m saying is kind of old hat. There’s a greater diversity of voices there. In other media it’s a different story. People are still hung up on Blade Runner as being the coolest look ever for a movie. And it was an amazingly cool movie, but it takes a while for new ideas and archetypes of cinematography to kind of make their way into the places where decisions get made.

MJ: You’ve tried various types of storytelling, from video games to interactive iPad novels. Why do you keep coming back to print?

NS: At the end of the day, I can just sit down and write a novel. I know how to do it, I know how to get it published. I don’t have to raise money and I don’t have to hire people. I don’t have to put together a spreadsheet explaining the revenue model. There are so many things, so many tasks like that that simply disappear when I just want to write a book. I’m interested in the problem of finding new ways to create media, but at the end of the day, if things aren’t coming together, I can always just say, “Fuck it,” throw up my hands, go into my office, and write.