The camo and calisthenics in these photos may call to mind a military academy, but they actually document a rehab center for internet addicts. China has more online gamers—368 million—than the United States has people. Perhaps it’s no surprise then that Chinese parents, psychiatrists, and media often describe wangyin, or internet addiction, as a clinical disorder. Sometimes called “digital heroin,” it is said to afflict 24 million young people. This center in a Beijing suburb houses 70 such patients, mostly boys, and is led by Tao Ran, a “tough love” former army colonel. While controversial treatments have been blamed for deaths at similar facilities, Tao claims his team’s methods—which can include brain scans and medication—have a 75 percent success rate. That’s welcome news for panicked mothers and fathers who, raised before China’s tech revolution, struggle to recognize the online lives of their children, and for a government that fears gaming is yet another way for the internet to corrupt young minds.

Tao Ran, a military doctor and researcher who built his career treating heroin addicts, runs the Internet Addiction Treatment Center. Among other tactics, the center deploys military discipline, drugs, and psychotherapy.

Residents head outside at 6:30 to start the day with exercises and drills.

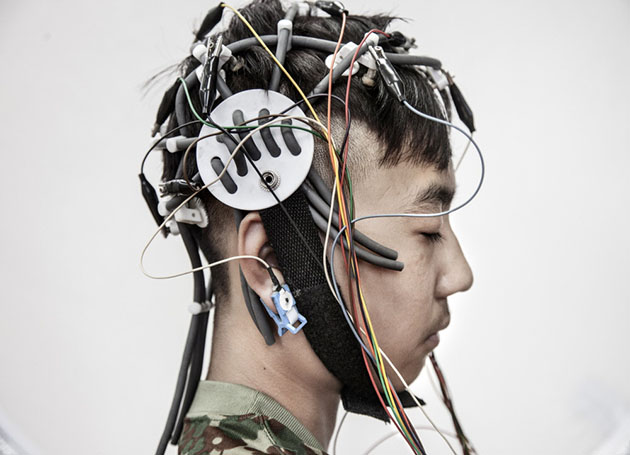

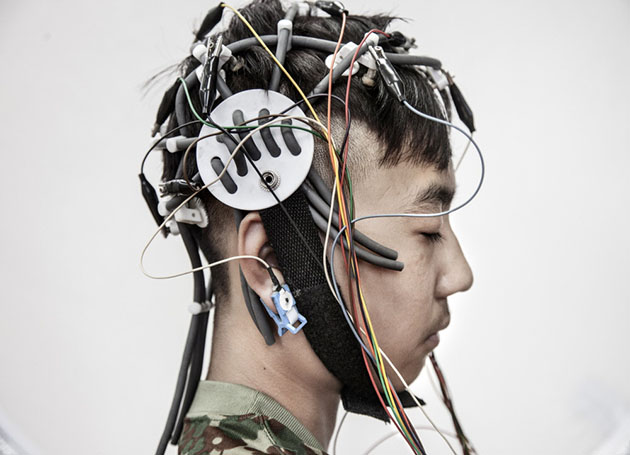

A resident is wired up for electroencephalogram scans to measure brain activity.

The center’s program includes military style workouts.

The center’s canteen.

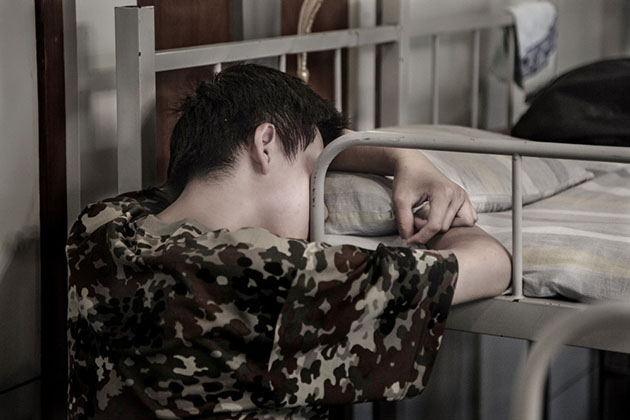

Inside a dormitory. The center encourages group activities, such as card games, to build socialization skills weakened by solo screen time.

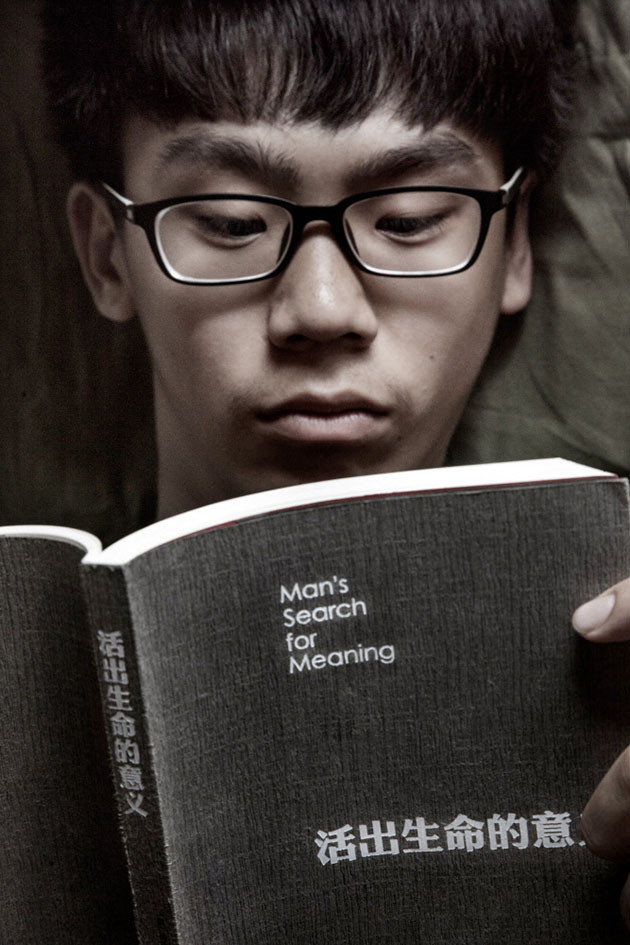

Residents look through books about internet disorders authored by the center’s director.

Medication for residents.

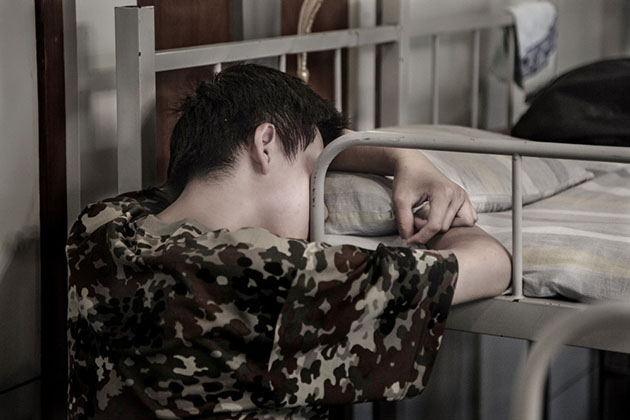

Wang Tai, 18, stands by his bed at the center.

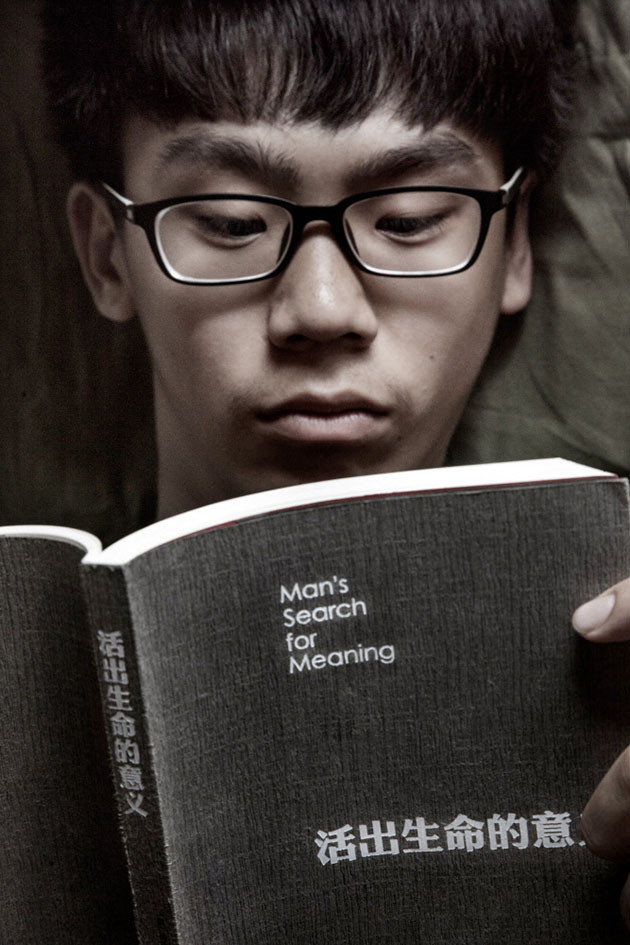

Xu Deyi lies in bed reading. What does the 17-year-old think of the book, which was sent to him by his mother? “It helps me to be aware of life, to realize the meaning of human existence. It shows me a clear way to achieve myself and encourages me to feel life every day.”