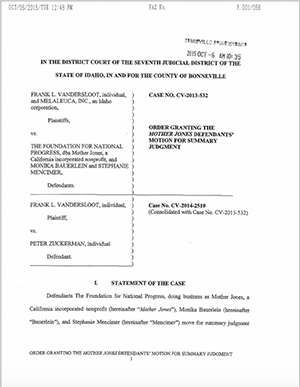

Today we are happy to announce a monumental legal victory for Mother Jones: A judge in Idaho has ruled in our favor on all claims in a defamation case filed by a major Republican donor, Frank VanderSloot, and his company, Melaleuca Inc. In a decision issued Tuesday, the court found that Mother Jones did not defame VanderSloot or Melaleuca because “all of the statements at issue are non-actionable truth or substantial truth.” The court also found that the statements were protected as fair comment under the First Amendment.

This is the culmination of a lengthy, expensive legal saga that began three years ago when the 2012 presidential primaries were in full swing. On February 6, 2012, we published an article about VanderSloot after it emerged that his company, Melaleuca, and its subsidiaries had given $1 million to Mitt Romney’s super-PAC. The piece noted that VanderSloot had gone to unusual lengths to oppose gay rights in Idaho, and that Melaleuca had run into trouble with regulators.

VanderSloot’s lawyers sent us a letter complaining about the article. We reviewed their concerns and posted a correction about a few details. So far, not an uncommon scenario; it’s something every newsroom deals with from time to time.

But that September, we broke the story of Romney’s 47 percent comments, which some have argued cost the GOP the White House. Four months later, VanderSloot—who was also one of Gov. Romney’s national finance chairs—filed a defamation lawsuit against Mother Jones as well as Stephanie Mencimer, the reporter of the article, and Monika personally (for her tweet about the piece).

People have asked us whether we think these two things were connected, and the honest answer is that we have no idea. What we do know is that the take-no-prisoners legal assault from VanderSloot and Melaleuca has consumed a good part of the past two and a half years and has cost millions (yes, millions) in legal fees. In the course of the litigation, VanderSloot sued a former small-town Idaho newspaper reporter whose confrontation with him we mentioned in our article. His lawyers asked a judge to let them rifle through the internal records of the Obama campaign. They deposed a representative of the campaign in pursuit of a baseless theory that Mother Jones conspired with Obama’s team to defame VanderSloot. They tried to get one of our lawyers disqualified because his firm had once done work for Melaleuca. They intrusively questioned our employees—our reporter was grilled about whether she had attended a Super Bowl party the night she finalized the article.

Legally, what we fought over was what, precisely, the terms “bashing” and “outing” meant in the context of our article. (Read the decision for yourself.) But make no mistake: This was not a dispute over a few words. It was a push, by a superrich businessman and donor, to wipe out news coverage that he disapproved of. Had he been successful, it would have been a chilling indicator that the 0.01 percent can control not only the financing of political campaigns, but also media coverage of those campaigns.

Throughout this lawsuit, VanderSloot appeared to be engaged in rewriting his own history of opposing the expansion of civil rights to LGBT people. His complaint focused on two things: He asserted that we defamed him by “falsely stating that Mr. VanderSloot ‘bashed’ and ‘publicly out[ed] a reporter.'” He also claimed that Monika’s tweet about the article defamed him by referring to “gay-bashing.”

In a way, there was something ironically hopeful about this: A conservative Republican—someone who not long ago was quoted saying it was “child abuse” to put a film about gay parents on public television—had apparently come to believe that to call him a gay-basher was so damaging to his reputation that he must fight the argument at virtually any cost. It’s a sign of just how far America has moved in just a few years that this entire case felt like something from a time capsule.

To be sure, VanderSloot has much at stake in reworking his public profile. He’s now widely recognized as one of the megadonors who will help determine who wins the 2016 GOP nomination. He has vowed to be even more “financially active” than he was in 2012, when he raised between $2 million and $5 million for Romney. In burnishing his image as a national figure, he might like people to forget about certain aspects of his past, such as the fact that he financed an ad campaign to amend the state constitution to ban marriage equality. (One of the ads pointed out that such an amendment would also prevent marriages between “a person and an animal.”)

“I have learned a great deal about the debate of homosexuality and sexual orientation,” he wrote in an op-ed this past February. “I believe that gay people should have the same freedoms and rights as any other individual.”

That’s a fascinating story. But it’s also a frightening one. If VanderSloot had prevailed, he would have proven that with enough money to throw at lawyers, you can wipe the slate. You can go after those who document the past and the present, and if you can’t make them cry “uncle” you can at least append a legal asterisk to their work forevermore.

That’s why we’ve pushed back. Frank VanderSloot may have evolved along with America. We respect that. But it doesn’t erase the past.

Perhaps fittingly, a major element in this case about the right of the press to afflict the powerful was a piece of investigative journalism. In 2005, a young reporter at the 26,000-circulation Post Register in Idaho Falls got a tip about a pedophile in the local Boy Scouts. The reporter, Peter Zuckerman, dug into the story and discovered legal documents indicating that scout leaders had received multiple warnings about a camp employee but had not removed him. The documents also indicated that the man’s bishop in the Mormon Church had been warned about him as early as 1988 and had sent him to counseling, but had told the Scouts years later that he saw no reason the man should not be a camp leader. In one case, according to a court decision, a 10-year-old’s parents told scout leaders they were concerned about the man’s behavior. When he was arrested the following year, scout leaders learned that he had molested the child, but decided not to tell the parents.

The series made a huge splash. It won a string of prestigious journalism awards. It became the subject of a PBS documentary. But there were also angry phone calls to the paper. Advertisers pulled out. And Frank VanderSloot got involved.

VanderSloot is reportedly the richest man in Idaho, and among the most powerful. His company, Melaleuca, sells tea-tree oil supplements and personal-care products via an Avon-like system of individual marketers who recruit others to sell. His net worth has been estimated as $1.2 billion, and for decades he has been a major power in Idaho politics, especially on LGBT issues. He financed an ad campaign that helped defeat a state Supreme Court justice on grounds that she might vote to legalize same-sex marriage. His wife gave $100,000 to the campaign to pass the anti-gay-marriage Proposition 8 in California.

In the late 1990s, he helped pay for billboards across the state protesting Idaho public television’s plan to air a film intended to teach kids respect for different kinds of families. The government, he said, should not “be spending our tax dollars to bring the homosexual lifestyle into the classroom and introduce it to our children as being normal, right, acceptable, and good and an appropriate lifestyle for them or anyone else to be living.”

VanderSloot has long been active in the Mormon Church, and he was a strong supporter of the Boy Scouts. When the Post Register‘s series ran, he swung into action. He took out full-page ads in the paper attacking the investigation and Peter Zuckerman, the 26-year-old lead reporter on the series. One of the ads noted that Zuckerman had written an article about his sexual orientation for a journalism site while on a fellowship in Florida. The ad said he had declared “that he is homosexual and admitted that it is very difficult for him to be objective on things he feels strongly about.”

“Much has been said on a local radio station and throughout the community,” VanderSloot’s ad continued, “speculating that the Boy Scouts’ position of not letting gay men be Scout Leaders, and the LDS Church’s position that marriage should be between a man and a woman may have caused Zuckerman to attack the scouts and the LDS Church through his journalism.”

“We think it would be very unfair for anyone to conclude that is what is behind Zuckerman’s motives,” the ad continued. “It would be wrong to do. The only known facts are, that for whatever reason, Zuckerman chose to weave a story that unfairly, and without merit, paints scout leaders and church leaders to appear unscrupulous, and blame[s] them for the molestation of little children.” Decoding the message between the lines is left as an exercise for the reader.

The ads had a dramatic impact. Though Zuckerman had been open about his sexual orientation before he came to Idaho, his editor Dean Miller later wrote that in Idaho Falls the reporter “was not ‘out’ to anyone but family, a few colleagues at the paper (including me), and his close friends.” Zuckerman had already gotten some negative reactions after a local talk show with a tiny audience discussed his sexual orientation. But according to Miller’s article and Zuckerman’s testimony in the litigation, things got much worse after VanderSloot’s ads. “Strangers started ringing Peter’s doorbell at night,” Miller said. “Despite the harassment, Peter kept coming to work and chasing down leads on other pedophiles in the Grand Teton Council. I spoke at his church one Sunday and meant it when I said that I hope my son grows into as much of a man as Peter had.” (Later that year, Zuckerman moved to Portland, where he took a job with the Oregonian while his partner was elected the city’s first openly gay mayor.)

Fast forward to 2012. Miller’s article about the Boy Scouts controversy was one of the stories that our reporter Stephanie Mencimer found after VanderSloot’s name popped up in the January campaign finance filings. It was the first presidential election of the dark-money era, and Mother Jones‘ politics team had zeroed in on the huge new super-PACs being created to pump unrestricted money into campaigns of both parties. VanderSloot stood out because Melaleuca was among the top contributors to Restore Our Future, the super-PAC supporting Romney. Mencimer wrote an article about him that included a few paragraphs on his history of anti-gay-rights activism and his run-in with the Post Register.

Those paragraphs are what VanderSloot and Melaleuca sued us over. They filed the suit in Bonneville County, Idaho, and asked for damages of up to $74,999—exactly $1 under the amount at which the lawsuit could have been removed to federal court. That ensured the case would be decided by jurors from the community where his company is the biggest employer and the sponsor of everything from the minor league ballpark to the Fourth of July fireworks.

Since then, Mother Jones and our insurance company have had to spend at least $2.5 million defending ourselves. That’s money we can’t get back, since Idaho doesn’t have an anti-SLAPP statute that might open the door for recovering attorney’s fees in a case like this. We also paid for the defense of Zuckerman, whom VanderSloot sued halfway through the case for talking to Rachel Maddow about his experience. (VanderSloot did not sue MSNBC or its deep-pocketed parent company, Comcast. Make of that what you will.)

Here’s a moment that gives you a sense of what it was like. At one point, Zuckerman was subjected to roughly 10 hours of grilling by VanderSloot’s lawyers about every detail of the controversy in Idaho Falls, including the breakup with his boyfriend of five years. (VanderSloot also threatened to sue the ex-boyfriend, backing off only after he recanted statements he’d made about the Boy Scouts episode.) As the lawyers kept probing, Zuckerman broke down and cried as he testified that the time after the ads appeared was one of the darkest periods of his life. VanderSloot, who had flown to Portland for the occasion, sternly looked on. (His lawsuit against Zuckerman is ongoing.)

And that wasn’t the end of it. VanderSloot’s legal team subpoenaed the Obama campaign, which had run ads naming him as a major Republican donor. Apparently they believed we had somehow fed the campaign that information—never mind that our article, and the Federal Election Commission data that prompted it—was on the internet for anyone to read.

When officials from the Obama campaign refused to turn over their records—offering to confirm under oath that there had been no communication between them and Mother Jones—VanderSloot’s lawyers dragged them into court, resulting in the spectacle of a major GOP donor seeking access to the Democratic campaign’s emails. His lawyers did the same thing to a political researcher who had gathered information on VanderSloot and who also had no connection to Mother Jones.

This kind of legal onslaught is enormously taxing. Last spring, Lowell Bergman, the legendary 60 Minutes producer (whose story of exposing Big Tobacco was chronicled in the Oscar-nominated film The Insider), talked about a “chill in the air” as investigative reporters confront billionaires who can hurt a news organization profoundly whether or not they win in court: “There are individuals and institutions with very deep pockets and unaccountable private power who don’t like the way we report. One example is a case involving Mother Jones…A superrich plaintiff is spending millions of dollars while he bleeds the magazine and ties up its staff.”

Litigation like this, Bergman said, is “being used to tame the press, to cause publishers and broadcasters to decide whether to stand up or stand down, to self-censor.”

Over the past three years, we’ve had to face that decision over and over again. Should we just cave in—retract our article or let VanderSloot get a judgment against us—and make this all go away? It wasn’t an easy choice, but we decided to fight back. Because it’s not just about us. It’s about everyone who relies on Mother Jones to report the facts as we find them. It’s about the Fourth Estate’s check on those who would use their outsized influence and ability to finance political campaigns to control the direction of the country. It’s about making sure that in a time when media is always under pressure to buckle to politicians or big-money interests, you can trust that someone will stand up and go after the truth.

And it’s about one more thing. Just a few years ago, no one thought that America could move so far, so fast, toward respecting the rights of gays and lesbians. No one thought that by 2015 same-sex couples would have a constitutional right to marry or, for that matter, that the Boy Scouts would rescind their ban against gay troop leaders and the Mormon Church would back them up. That happened because a lot of people stood up to threats and discrimination. They came out to their families and communities. They declared their love for everyone to see. They didn’t let themselves be intimidated. Nor will we.

Postscript: In her decision Tuesday, the district court judge found in our favor on every single claim VanderSloot had made. She also included a passage expressing her own opinion of Mother Jones, and of political news coverage in general. For his part, VanderSloot issued a statement saying he had been “absolutely vindicated” and announced that he was setting up a $1 million fund to pay the legal expenses of people wanting to sue Mother Jones or other members of the “liberal press.” We’ll leave it with the reaction from our lawyer, James Chadwick: This was “a little like the LA Clippers claiming they won the NBA Finals. I think everyone can see what’s going on here.”