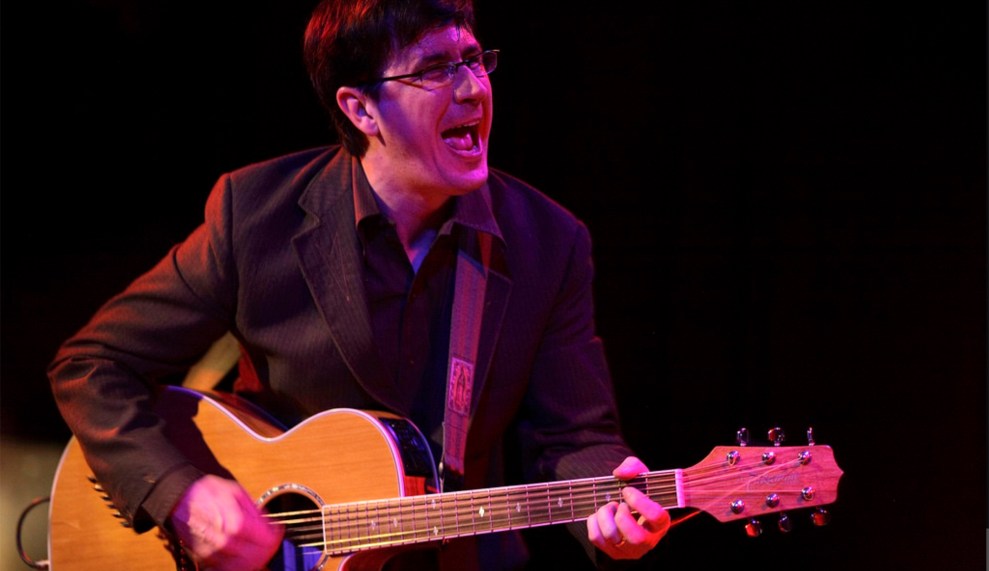

Jonathan Meiburg defies easy categorization. He’s the frontman of Shearwater, a critically acclaimed indie band and Pitchfork darling. He’s a writer with a book contract. He’s one the last people to conduct an interview with the late, elusive author Peter Matthiessen.

Last but not least, Meiburg is an amateur ornithologist whose research has taken him from New Zealand’s Chatham Islands to the Arctic, with dozens of stops in between. When we spoke, he was in London researching his longtime obsession: a South American bird of prey that will feature prominently in his upcoming narrative nonfiction book.

In fact, Shearwater’s nine LPs to date often revolve around themes of nature in general and birds in particular. But Meiburg doesn’t want to be “pigeonholed, so to speak, as ‘that bird guy.'” Out today, Jet Plane and Oxbow is a testament to that. The new album’s soaring, epic tracks delve into everything from American hubris to the place of humans in geographic history. They draw elements from ’80s experiments, such as David Bowie’s Scary Monsters and Peter Gabriel’s Melt, using electronic layering and hooks to create a “3D movie for you ears,” as Meiburg puts it. Indeed, these songs are sonically rich, lyrically dense, and, although catchy on first listen, require time and concentration to fully appreciate. I caught up with Meiburg to talk about birds, music, and our nation’s militarist tendencies.

Mother Jones: Tell me more about this book.

Jonathan Meiburg: It basically looks at 10 species of caracaras, which are strange, super-intelligent South American birds of prey. Through them and the people who live with them, it tells the story of the evolutionary history of South America and its wildlife. I’ve been spending a lot of the year in Southern Guyana and Brazil visiting the different caracara species and people.

MJ: These birds don’t have the greatest reputation.

JM: As Darwin said, they take the place of crows, magpies, and ravens in South America because there are no crows there. They are scavengers and omnivores. They’ll hunt things, but they also like to eat dead stuff. People have a real prejudice against animals that eat dead stuff.

MJ: What drew you to them?

JM: They have an usually conscious presence. They look at you and you can feel them recognizing you as something like them, somehow. The avian forebrain is like our forebrain and has a lot of the same capabilities that have to do with social intelligence and self image—magpies can recognize themselves in a mirror—and projecting yourself forward and backward in time. Their forebrain is derived from a different structure within the brain than ours is. So this consciousness evolved convergently with ours, yet it’s so close in its outcome that we are actually able to do things like talk to parrots in English. Nobody’s looked at caracara brains, but I’d be pretty surprised if they didn’t also have a pretty large forebrain.

MJ: How did you get interested in studying birds?

JM: After college, back in 1997, I got this strange fellowship, the Thomas J. Watson fellowship. I had proposed a study of community life at the ends of the Earth. I’d never really left the Southeast, so I wanted to go to places as far-flung as I could imagine. To my surprise, I got this grant, and my poor parents had to put my on a plane to Tierra del Fuego when I was 21. From there I went to the Falklands, where, in a boarding house in Stanley, I met a man named Robin Woods—a great name for an ornithologist.

He was leading a survey of striated caracaras that lived in the outer islands and fed on penguin and albatross colonies. I convinced him to take me along as an assistant, and for seven weeks we sailed on a wooden boat that was built in the 1920s to these outer islands, walking the coastlines to search for breeding pairs. It’s just an incredible place to learn about birds because the birds are very tolerant of human presence—or even curious about you, in the case of the caracaras. They’ll come up and try to take things out of your bag. It’s just not afraid of you. You realize, “God, the whole world used to be like this!” And now it’s just tiny little fragments. It just blew my mind, and it opened my eyes to the world of birds in a way that stayed with me. When I came back, I went to the University of Texas to study geography. I did a thesis trying to examine the riddle of why these striated caracaras were only in Tierra del Fuego.

MJ: By that point were you already making music professionally?

JM: Yes, I had started playing in bands in Austin two years before grad school. And then I started playing in this band Okkervil River. And then, with the singer of that band, I started Shearwater. The two bands progressed together for a while, and then eventually I left Okkervil and just kept on going with Shearwater. My two-year degree took six years because I was ducking off on tour. I remember turning in my thesis on the same day we left on a European tour. So the music started overwhelming the academic part of my life, which I felt very conflicted about for a long time, but now I feel grateful.

MJ: At some point, you would have to choose.

JM: Yes. It became very clear I was going to have to give the music up if I was going to pursue an academic career. I remember calling my professor who was going to supervise me if I did a biology PhD—from a truck stop in Oklahoma, we were on tour—and telling him I just couldn’t do it. Years later, he turned up at a show we played at South by Southwest. He said, “I’ve been following your band and I think you did the right thing.” I could have kissed him.

MJ: But you didn’t give up research completely.

JM: I realized there was maybe a role for me that didn’t involve being a research scientist. That there was something else I could be that could still intersect with the lives of these creatures. It’s been a long road, full of a lot of doubt and missteps and many moments of, “Oh my God, what am I doing with my life?” In the last year or two, it’s started to settle out in a way that makes me feel like maybe I’m through the worst of that. But it took a long time. For me, the interest in the natural world and the music don’t feel like separate pursuits. They feel like attempts to answer the same questions.

MJ: Yes, a lot of your music does seem to be about birds and nature.

JM: The wonderful thing about looking at any kind of wildlife is it takes you out of the human world and starts to make your own life look different—in the same way of when you go away from home for a long time and come back: For a few days, home just feels like another place. Those couple of days are really valuable because they show you things about the place you live that you haven’t noticed before.

MJ: This new album goes way beyond wildlife.

JM: I heard an interview with David Bowie from 1980 where he described Scary Monsters as social protest music. I kept thinking about that: Is it possible to make a protest record now that’s not hectoring, that doesn’t bang you over the head or insult your intelligence, and yet still is a polemic in some way? So I’ve tried to make Jet Plane and Oxbow as a protest record in a sort of oblique way. It’s very much about the United States. The United States has got a lot going for it, but it’s very sick. It’s battling some real infections, and whether it is going to win out is not clear. “Wildlife in America” is partly about the seductive qualities of militaristic thinking in America. You and I lived through the run-up to the Iraq War—how weird that was: on TV, all the snare drums and martial music and images of fighter planes, and strange equivalencies where they would show this shot of Saddam Hussein shooting a rifle in the air and then a shot of George W. Bush, like it was going to be a WWF Smackdown. Talking about these things, you very quickly enter this liberal echo chamber. All the same, the seductive nature of trying to protect American power is really fed to us like mother’s milk.

With the song “Stray Light at Clouds Hill,” I was partly thinking about drone pilots. I was reading an interview with people who had piloted drones used in Afghanistan about the disconnection between who they were and what their lives were like and what they were actually doing. I remember one guy saying he had stepped outside after conducting some sort of a drone strike, outside the trailer in Nevada where he was working, and he said, “All the brightest were too bright; everything dark was too dark.” In a way, that’s how I feel about the United States.

MJ: Are you hopeful about our fate?

JM: I don’t know! We are surprising. The United States can engage in moments of national self-reflection that are pretty startling. I’m from the Southeast, and I’ve been amazed to see the excuses for the Confederate flag finally being swept away. I just figured it was here to stay. I still have hope, but as we grind into yet another election season, oh boy, the national id just comes roaring out of the closet—all of the worst things come bubbling up to the surface. Which might be a good thing because you see them for what they are. But it sure is ugly to watch.

MJ: The songs on this album are beautiful and catchy, despite some heady themes.

JM: I was trying to convey a sense of these big emotions: wonder, anger, indignation, fear, joy. Pretty intense emotional states, really heightened emotional states. And music is a wonderful way to take you there in a very immediate way. A three-minute song can take you through emotions that it might take you all day to work up to otherwise. I wanted it to be an album that you could listen to and enjoy the first time you listened, but repeated listens would also reward.

MJ: Where’s the title from?

JM: I was flying from Austin back to New York, where I live. There is this set of oxbows on the lower Mississippi—they look like curlicues coming off the river, almost perfect three-quarter circles. I was looking down at this mesmerizing symmetrical feature of the landscape that was very ancient, and then a plane headed the opposite direction passed right smack through the center of that oxbow and pierced it. The juxtaposition of those two things seemed like a good image to me.

MJ: You mentioned that this is a protest record. What are your thoughts on music being political?

JM: It has to be good art first. I don’t like slogans—of almost any kind—because they tend to grind the subtleties of arguments to dust. The quality of any protest—and this is actually what Occupy had going for it—is that for a moment nobody knows what to do. As the chant went, “Another world is possible.” It opens the door to a different way of being, like a sit-in at a lunch counter—it changes for a moment the world that you live in. And when protests, whether an organized march or protest music, when it goes too much to a script that you already feel, I would say it’s compromised. I make music about wildlife and nature, but the kind of art I like in general has multiple opposing currents. I think the most effective art manages to make opposing realities coincide.