DAVID PILGRIM bought his first piece of racist memorabilia in the early 1970s, when he was a youngster in Mobile, Alabama. It was a set of salt and pepper shakers meant to caricature African Americans. “I purchased it and broke it” on purpose, recalls Pilgrim, who is black. Yet over the next few decades, he amassed a sizable collection of what he calls “contemptible collectibles”—once-common household objects and products that mock and stereotype black people.

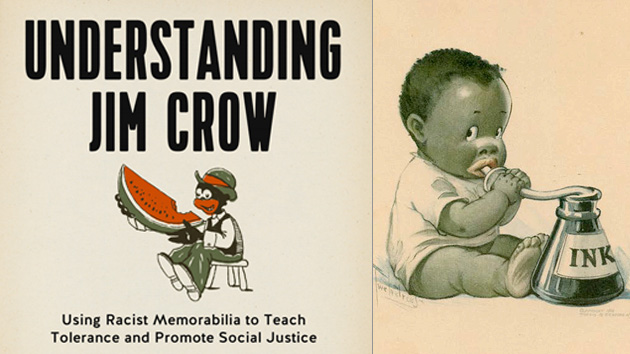

In 1996, Pilgrim transformed his 3,200-item collection into the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia at Michigan’s Ferris State University, where he teaches sociology. He presents a selection of these appalling objects and images in his new book, Understanding Jim Crow: Using Racist Memorabilia to Teach Tolerance and Promote Social Justice. As the title implies, the book isn’t merely an exercise in shock value. It lays out the philosophy behind Pilgrim’s work as a scholar and an activist: that only by acknowledging these artifacts and their persistence in American culture can we honestly confront our not-so-distant past.

Mother Jones: What made you decide to turn your collection into a museum?

David Pilgrim: When I got to Michigan, someone mentioned that they knew this elderly black woman who was an antiques dealer. After many months, she agreed to let me see her personal collection. It was just objects floor to ceiling in a barnlike structure. I was overwhelmed by the sheer volume. It shook me! I thought I’d seen everything. What she had was a testimony to—this is going to sound weird—not just the creativity of racism, but the diversity in it. I remember that day thinking that I wanted to do what she’d done, but in a different way.

MJ: How popular were these collectibles?

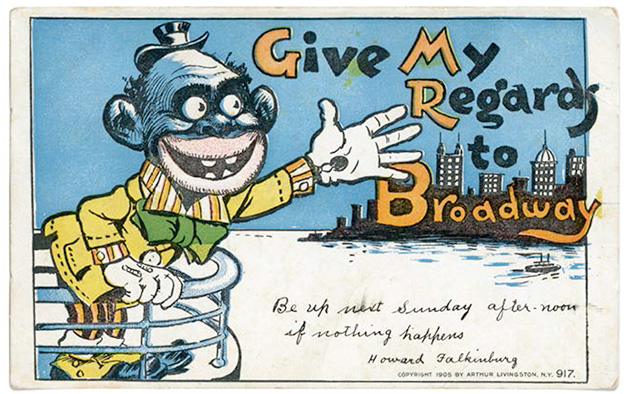

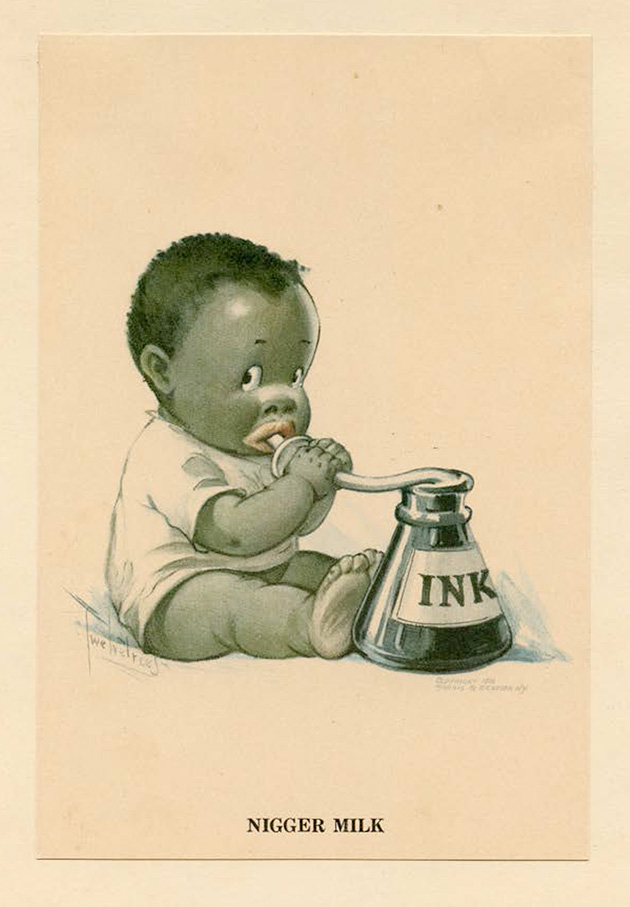

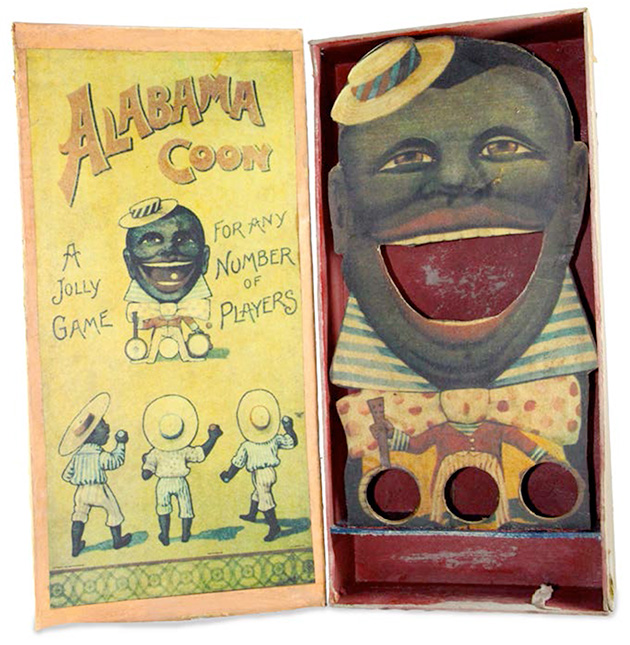

DP: They were everyday objects in a lot of people’s homes, including African Americans’. [The antiques collector] had postcards, posters. She had records, 78s. She had ashtrays. She had a racist bell. I think she had the game called Chopped Up Niggers—it’s a puzzle. She told me that she hadn’t paid very much for many of those pieces because at the time people were throwing stuff away. Some people were ashamed.

MJ: Why own them in the first place?

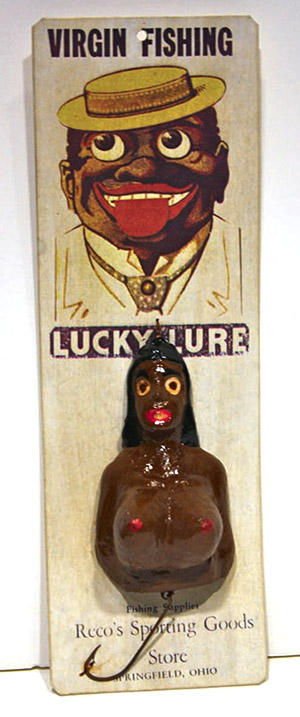

DP: These toys, games, sheet music about “coons” and “darkies”—all these millions, and I mean literally millions, of objects—were integral to maintaining Jim Crow. Jim Crow could not work without violence, real violence, but also the threat of violence and the depiction of violence. There are a number of games in the museum where you throw things at black people: “hit the nigger” or “hit the Negro” games. If you had such a game, you were actually creating safe spaces to do that.

MJ: Do you also keep track of racist images and memorabilia online?

DP: Absolutely. With the power of the internet and social media, one person can do the damage that in the old days it took many to do. When you have a race-based incident—and I make it my business to look—within one week there are material objects that reflect that incident in a racist way: lunch boxes, posters, puzzles, T-shirts, pillows. President Obama has been an industry for racist objects. He has been portrayed as a witch doctor, a Rastus character from Cream of Wheat, as a Sambo, as an Uncle Tom—and also as gay, as transgender, as communist, as socialist, as a terrorist, as a Muslim. [Many of the] images that appear online are old. The images from the old “coon” songs from the late 1800s and early 1900s show up in memes, and people don’t realize they’re older images.

MJ: What sort of people collect this stuff?

DP: There are some who want to educate. I’ve met collectors who collect to destroy the pieces. But by far the biggest segment are speculators who know that a McCoy cookie jar was $3 and you can get several hundred dollars for it now.

MJ: Do you see a role for your collection in today’s movement for racial equality?

DP: One of the questions I get often is why we’re still having these conversations. And my answer is: The objects are still being made, they’re still being sold and distributed. There’s not an image in the museum that’s not being reproduced in some way. Secondly, the reason we still have these discussions is because race still matters. But Americans don’t often talk about it in places where their ideas are challenged. We want our museum to be safe but uncomfortable.

MJ: I found myself hiding your book from my kids. At what age do you think it’s okay to expose children to this stuff?

DP: I believe that young people—8, 9, 10—should have discussions appropriate to their age about race. But no one under 12 can come into the museum by themselves, and we discourage parents from bringing them. Right in the center of the room is a lynching tree. Even though it’s contextualized, it can be a house of horrors.