Ben drove a car I coveted. A bright yellow Karmann Ghia. Slick, low, designed for Volkswagen in an Italian studio famous for its sports cars. The very quintessence of cool to my eight-year-old self. The trunk of the Karmann Ghia, like the Volkswagen Beetle, was in the front, under the hood; it seemed to me like another in Ben’s repertoire of magic tricks.

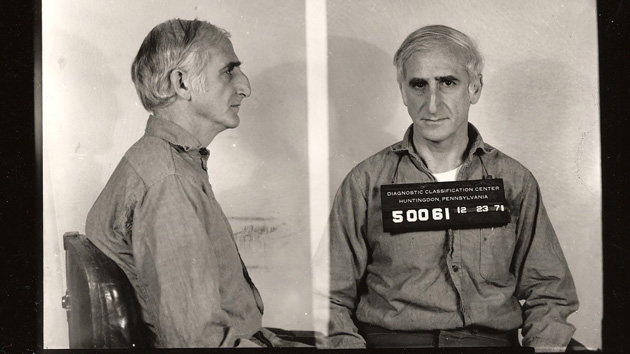

One night in 1971, Ben drove that car to the Mayflower Hotel in Washington, DC, opened the hood, and helped US Sen. Mike Gravel move two heavy boxes of documents into the senator’s car. Inside was a classified history of the Vietnam War that would soon become known as the Pentagon Papers. (Ben once told an interviewer, “I drive down in my Karmann Ghia and he’s got a couple of aides there and I said, ‘This is heavy, you may want your aides to carry it.’ He said, ‘No, I have immunity and they don’t.'”) The senator from Alaska drove off toward Capitol Hill, where he planned to read the papers out loud, into the congressional record. Ben, then an assistant managing editor at the Washington Post, drove home.

I knew the phrase “Pentagon Papers” long before I understood its meaning. As I grew up, I slowly came to understand that Ben had earned his stripes as one of the most conscientious of American journalists, having served in the trenches of some of the seminal battles of post-World War II America: He covered the civil rights struggles in the Deep South; he went undercover in prison (pretending to be a convicted murderer) to report on the criminal justice system; he regularly took on big government and corporate America when he felt that either infringed on First Amendment rights.

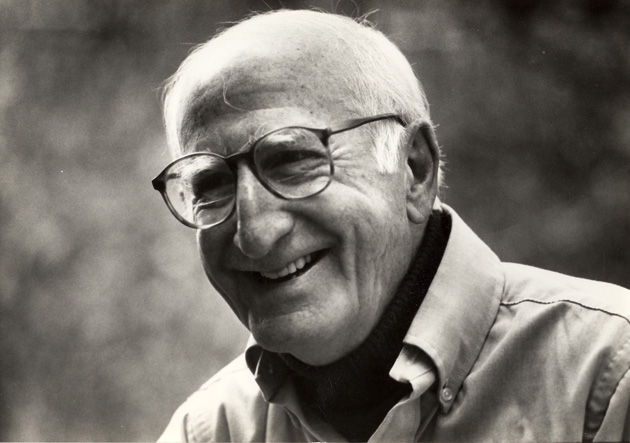

In 1976, when Ben moved to Berkeley to teach at the university, he had already touched most of the bases: reporter, editor, national and foreign correspondent, ombudsman. He was writing for some of the most important newspapers and magazines in the country. In Berkeley he was embarking on a teaching career that was to inspire a new generation of journalists. He became friends with my parents, both journalists, and an important part of our family life. I think of Ben and his wife, Marlene, around our dinner table, where the conversation was always lively and my brother and I were expected to take part. At times, the two of us would decamp to the Bagdikian home for a few days, where Ben kept track of how much we had grown, in pencil marks along a doorframe.

Ben became a forceful voice as a critic of the media; the first edition of his book The Media Monopoly became a standard text for many college classes. But he also never stopped encouraging young people to throw themselves into the fray. I saw him for the last time a few weeks ago; I sat up close, so he could hear me and so I could hear him as well. Usually he held my hand. Always, what he wanted to talk about were the stories the magazine was working on. In these last months, Marlene’s routine has been to rise early and bring in the morning papers, then return to sit down on a chair in the bedroom to wait for Ben to wake. “When he opened his eyes,” she said, “his first words were, ‘Show me the headlines.'”

The day after Ben died last week the New York Times and the Washington Post published detailed obituaries—along with the San Francisco Chronicle and many others. But I’m certain that he would be less interested in talk of his legacy than in a dialogue on the state of the media today, and how it is meeting its responsibilities in the frenzy whipped up by the 2016 election campaign. A big story with huge First Amendment considerations.

Still, what a legacy. Something none of the obituaries note are the throngs of young people Ben influenced, starting with his son Chris, who died last year and was a longtime reporter in California’s Central Valley. Scores of students took Ben’s courses at Berkeley’s graduate school of journalism and kept in touch with him. There are young family members whom he watched over. And there is the Ben Bagdikian Fellowship at Mother Jones.

The program was named in Ben’s honor about a decade ago, when it went through a significant expansion to become one of the premier training opportunities for young journalists. Critical in that effort was MoJo board member Carolyn Mugar, who, like Ben, was also Armenian. Soon after the new name was announced, Ben came to the offices to speak about the importance of genuinely independent journalism, unfettered and free to follow the story wherever it leads. Close to 100 fellows have completed the program since it took his name.

The Media Monopoly (and its many editions) became a seminal work about the state of journalism in America. Today, though, I’d rather send you to his memoir Double Vision, written in 1995. Journalism has changed in drastic ways in the 20 years since Ben wrote the book, but his words remain prescient:

Too much of our national reporting makes legends of political gods with endless detail on the speculations, warnings, encouragements, markings in the sand by pollsters and reading of entrails by soothsayers of Wall Street, the exchange rate killing made by King Midas, and the projected quarterly earnings of the builder …

A better central theme for our reporting is what politics and economics do to advance or defeat social justice. The conventions of our trade claim that social justice is in the eye of the beholder and therefore cannot be “objective” reporting. But in a democracy, is basic social justice really a matter of personal opinion? …

It is better to be fed than to starve, to be healthy than needlessly diseased, to be properly housed than live in decrepitude, to get a good education in a learning environment rather than be stuffed with irrelevance in a setting of squalor, to work rather than be idle—to have a decent regard for the health of the whole community instead of a heedless race of every individual for personal gain alone.

Lapses and failures in the struggle for a better democracy deserve a commanding place in the national dialogue, which means in the news. …We need the cold-eye reporting of the factual realities of the streets, the police station, the neighborhoods, the politics, the legislature, the stock market and the nations of the world. But we need constantly to measure how this cold-eyed vision helps or hinders the achievement of true democracy and genuine social justice.