<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/cat.mhtml?lang=en&language=en&ref_site=photo&search_source=search_form&version=llv1&anyorall=all&safesearch=1&use_local_boost=1&autocomplete_id=&searchterm=old%20person%20listening%20to%20music&show_color_wheel=1&orient=&commercial_ok=&media_type=images&search_cat=&searchtermx=&photographer_name=&people_gender=&people_age=&people_ethnicity=&people_number=&color=&page=1&inline=276870965"> berna namoglu</a>/Shutterstock

You’ve just gotten home after a long day at work. You pour yourself some wine and put on one of your favorite albums to listen to while you make dinner. Maybe it’s Dylan, a Mozart symphony, Taylor Swift’s 1989—no judgment. You hit play and turn up the volume, but something’s way off. Those perfectly crafted songs sound more like TV static than music, and there’s nothing you can do to fix it.

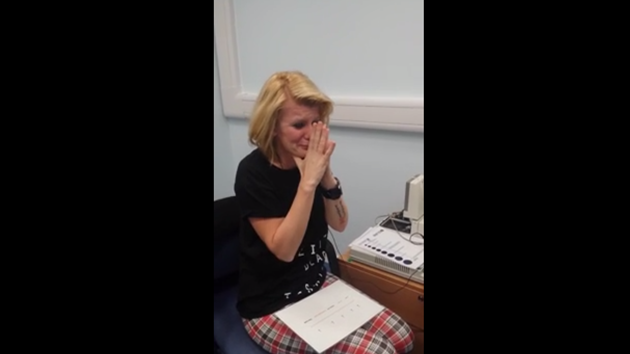

That scratchy, unpleasant noise is how music sounds to people whose failed hearing has been revived by a cochlear implant. Unlike a hearing aid, which amplifies sounds, these devices—implanted by a surgeon—convert sound into electrical signals and deliver them straight to the brain’s auditory nerve. It’s a solid choice for people who can’t be helped by hearing aids, drastically improving their ability to distinguish words in a conversation. Just witness this video of a deaf woman hearing for the first time.

But the implants can’t restore normal hearing: Voices often sound artificial, mechanical, even cartoonish. With music, it’s even worse. “It’s very disheartening for me to go to, let’s say, a piano concert and see on the program three pieces that I either know really well—or I actually not only know, but have played,” one implantee explains. “And they start up, and I’m thinking, which piece is this?” To get a sense, listen to the recordings below, courtesy of the Columbia Cochlear Implant Center, of the blues-country song “Milk Cow Blues.” The first track is what the song sounds like to you. The second one demonstrates how it would sound to a person with cochlear implants.

Some researchers are trying to make cochlear implants more music-friendly, but it’s no easy task: The devices are already quite sophisticated, and it’s difficult to encode pitch in real time. Dr. Anil Lalwani, director of the Cochlear Implant Center at Columbia University Medical Center, is trying a different approach: Instead of tweaking the implants, he’s tinkering with the music itself, trying to engineer songs that even the hardest-of-hearing can enjoy.

The key, he believes, is to simplify. Music is far more complex than speech, and people with the implants may be overwhelmed with so much auditory information. So Lalwani’s team of medical students and audiologists is pinpointing exactly which parts of music are critical for enjoyment and which can be stripped away. It’s largely a process of trial and error: The researchers have implantees listen to 20 variations of songs that range from “Happy Birthday” to the theme from 2001: A Space Odyssey. Some variations may have just one instrument or a combination, while others include vocals. The subjects rate their enjoyment of each version.

“Nearly everything we put together,” Lalwani says, “was more enjoyed than the original piece of music.” In particular, people with cochlear implants preferred rhythmic instruments like a snare drum to melodic ones such as violins, which often sound noisy to them. They liked fewer harmonics and shorter reverberation—the length of time it takes a note to fade. “Once we know what kind of music they like, what features they like, we can compose music specifically for them,” Lalwani explains. Here’s one version of “Milk Cow Blues” with just a snare drum track, and another with just acoustic guitar.

This next version combines snare drum with vocals and shows what that would sound like for someone with cochlear implants.

The doc told me he doesn’t know of any other researchers trying to create music for cochlear implantees. But he’s not the first to theorize that music could be tailored to the needs of a particular group—human or otherwise. A cellist from the National Symphony Orchestra has for years composed music specifically for cats—he’s also experimented with monkey “dance” tunes. (He theorizes, as the Washington Post reports, that music hits an emotional nerve by playing around with sounds we hear as we develop in the womb. For instance, we may find a song relaxing if it’s the same pace as our mother’s resting pulse—which could explain why monkeys with faster pulses dig upbeat dance music.)

When it comes to crafting the music, Lalwani is aiming high. He’s reached out to composers at Juilliard and intends to bring them on board to craft new songs with more rhythmic instruments and vocals. He eventually hopes to create a smartphone app that will fine-tune music according to individual preferences, based on the results of a brief battery of tests. “You take the original piece of music and alter it the way you like it,” he says. Nearly 100,000 Americans have cochlear implants, but Lalwani says the app might also help the tens of millions with hearing aids—and perhaps even people with no hearing problems whatsoever will like it. In his team’s tests, individuals with regular hearing have said they prefer variations with slightly less harmonics than the originals. Why? Sounds more natural, they say.

So, take heart: You may not have to give up music as the gray hairs come in and your hearing starts to fade. If all goes well, you could be rocking out at dinnertime to your favorite songs, specifically tailored to your needs—or, for pet lovers out there, those of your cat.

This post has been updated.