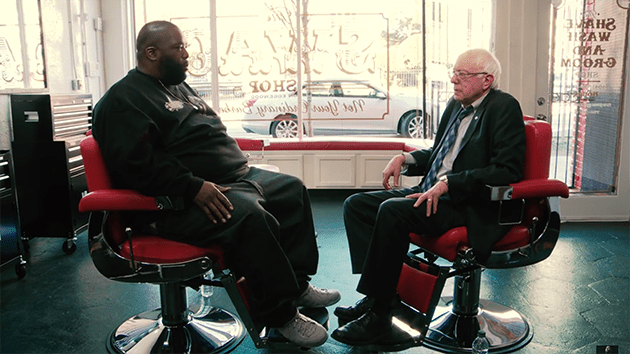

"I was reckless with records. I would put my hands all over them."Courtesy Grandmaster Flash

As a music-obsessed teen growing up in the Bronx in the 1970s, Joseph Saddler noticed that every party song had one drum break or keyboard solo that made dancers go wild. What if you could string those fragments together to create a nonstop frenzy?

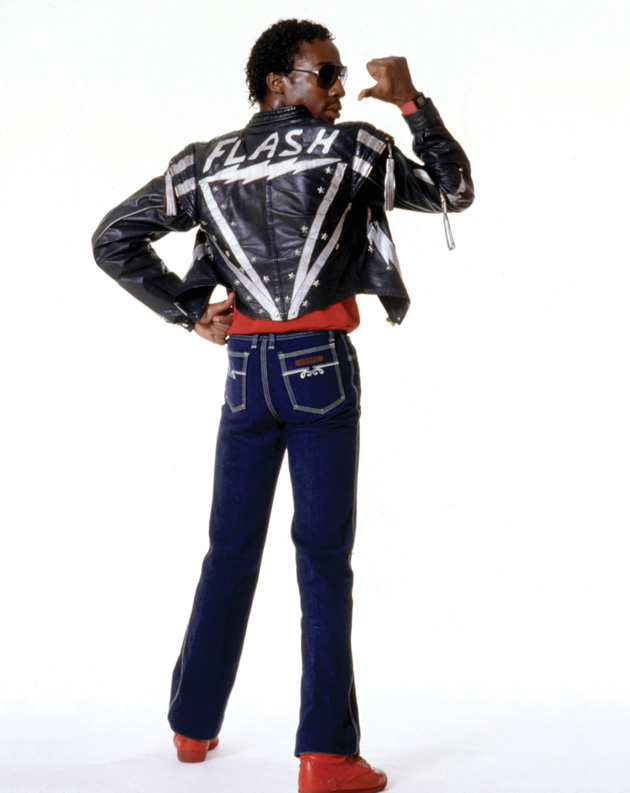

So Saddler, an electronics student at Samuel Gompers Vocational High School, set about transforming the humble turntable into an instrument. Using a jerry-rigged cross fader and two platters side by side, DJ Grandmaster Flash, as Saddler rechristened himself, helped lay the foundation for the emerging “hip-hop” style. He and his now-estranged crew, the Furious Five (which he won’t discuss due to a legal dispute), shared in some of the genre’s earliest hits, such as “Freedom,” “New York New York,” and “The Message.” In 2007, they were the first hip-hop artists inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Now Flash is revisiting those seminal days as an associate producer on The Get Down, a new Netflix drama set in ’70s-era New York. The series, which launches in mid-August, was created by movie director Baz Luhrmann and includes actor Mamoudou Athie as the youthful Flash. We asked Alan Light, a founding editor of Vibe and former editor-in-chief of Spin magazine, to run a mic check with the Grandmaster.

Alan Light: So how did you and Baz Luhrmann connect?

Grandmaster Flash: A call and an email came into the office. I didn’t know the name, but I read his film credits and was like, “Oh shit! It’s that movie where the guy never gets the girl!” The Great Gatsby kind of broke my heart. I watched it three times. So I go down to his place and Baz takes me into this huge room, and he’s got a timeline in Sharpie from ’69 up to ’79. I’m like, “This fuckin’ guy is doing his research!” He says, “Can you explain how you came up with this thing where you put your fingertips on the records and manipulate it back and forth?” I did a kind of hand motion, and he says, “Stop. I’m gonna give you a Sharpie and a piece of paper. Please explain it with a Sharpie.” The next time that I see him, it’s in a frame!

The first rap record came out in ’79, but hip-hop began in ’69. So what were we doing? A lot of journalists say, “Tell us about the ’80s.” Nobody wants to know about the ’70s! And so, I became Baz’s consultant and his historian and then assisted him with wardrobe and props—we wore those sneakers, we dressed like this, we drank this, the mixers were this model. There’s no such thing as a perfect historical film, but he wanted to get it right so bad that he’ll ask you the same question 50 times. My phone rings: “What street was it on? Who was there? What happened? Why?” I gotta tell you, Alan, the factual and the mythological glue together in this series—it’s gonna stir up emotions.

AL: Has looking back on all of this changed your perspective on the birth of hip-hop?

GF: Hip-hop has always been chronologically misunderstood. Too many times, people are hearing the story from the second floor. Nobody’s heard the story from the basement. If hip-hop was a cake, all I can tell you is the eggs, the flour, the sugar, the vanilla—the ingredient years. This is what Baz wanted to put on film.

AL: What was the hardest part?

GF: After a month or two, Baz says, “Flash, I would like to make you a character.” I says, “Hell no! I’m not going in no film.” He says, “No, I want a young Flash—someone to play you.” Two months later, I meet somebody that looks like I made him. “What’s your name?” He says, “Mamoudou. I’ve been hired to play you. I want to learn everything about you.” The hardest part was teaching him how to DJ. After three months, he finally got it.

AL: The kid really does look like you.

GF: I actually asked him, “What’s your mom’s name?” I didn’t know it, so I was like, “Thank goodness!”

AL: Let’s go back. What started you down the road toward turntablism?

GF: I was annoyed with the way DJs were playing. The part that would get people dancing the hardest would be the drum solo, but that break was always like 10 seconds long. I was like, “What the fuck? I have to be able to make one long song of the drum solos.” So I did research on needles, elliptical and spherical, and torque theory—how long does the platter on the turntable take to take off? Then mixers: I needed to be able to hear the mix before you do—that’s when I came up with the “peek-a-boo” system. But there was a problem. A new turntable had a mat, like a big rubber pancake—too much drag.

My mother, God bless her, was a seamstress. I remember going to a material store and feeling all the fabrics. I bought two pieces of felt the size of an album, but they were too limp, so when my mother wasn’t looking I hit it with spray starch. I turned the iron all the way up and turned the felt into what I called “a wafer.” My mother had a plastic baking sheet. I cut that out. I put the felt on top of the plastic and the record on top of the felt. Now I had the fluidity to make the record move, but the turntable didn’t have enough torque.

It wasn’t until I’d seen this extremely ugly turntable—this unknown company called Technics—in the window of this store in Hunts Point. I remember asking, “Can you take that turntable out of the window?” The salesman looks at me like, What? He thought I was coming in to rob them. I said, “I’m doing a science experiment.” I wanted to feel the pickup. I said to the boss, “How much?” He said $75 apiece. I saved up and I got them. These turntables played a major role: I created a music bed so that the speakers could tell their stories.

AL: Did any of this feel revolutionary to you at the time?

GM: I was in the moment. I just wanted to extract the drum solos and glue these things back to back. For what reason? I didn’t know. It’s just how I heard the record. The record was shit. I didn’t care about it.

AL: When did you sense that this was going to be big?

GF: When I tried getting a job as a club DJ. In the ’70s, anybody who was a connoisseur of collecting vinyl had the velvet brush. Remember the velvet brush? It would clean the record, and you would only grab the record from the sides and you would carefully slide it into the jacket. I never had a velvet brush. I was reckless with records. I would pull them out by my fingertips. I would put my hands all over them. So the word had got around that this dude Flash, he’s spinning the record counterclockwise. He’s going backward and he’s got these crayon marks on the record—he’s totally disrespecting the records! But slowly it became the way. I tried teaching people and it was like, “How did you come up with this shit?” I never came outside! This is what the fuck I was doing.

AL: So then what you’re doing starts getting out there. You release the “Wheels of Steel” single and do the now classic DJ-in-the-kitchen scene in the movie Wild Style. For me growing up in Ohio, that stuff was from another planet.

GF: For a long time, I was in denial. I just loved doing it. Then Frankie Crocker from WBLS—I was tuned in—and he says, “I’m getting ready to play you something that you’ve probably never heard before: This is DJ Grandmaster Flash, and it’s called ‘Adventures on the Wheels of Steel.'” Nobody told me they had brought the record down to him. I was like, “Oh shit!”

AL: In the early days, DJs were the focal point of hip-hop culture, but later the rappers moved front and center. How did you feel about that?

GF: I couldn’t understand why the record companies didn’t let the DJ be the music—that they had to bring a band in. I guess the [copyright] clearing was probably hugely expensive, but at that point I didn’t understand. I wasn’t angry, just confused. We were playing the greatest drummers on the planet back to back. Why wouldn’t you want that? And certain records, there’s that dirt, that fuzz, that thing—I don’t care what band it is, they can’t copy that.

AL: What’s your take on today’s hip-hop? I miss the kaleidoscope of records.

GF: I think a lot of that shit is dope. Drake is incredible. But I miss the kaleidoscope of records. You could go from, you know, sneakers—Run-DMC—to loving black people, that’s Chuck D; and then you go to Rakim, who was incredible at words, and then LL and then Grandmaster Flash. That diversity of production styles and diversity of lyrical structure—I miss that.

AL: It does seem like now it’s all about chasing one hot sound at a time. But on the other side of things, DJing has become its own massive industry.

GF: It’s bigger than ever. I used to travel 200 days of the year. I had to calm it down because I have a 17-year-old daughter going on 30, and a 23-year-old son. I want to be around for them. But to this day, whenever I go into a club and I see someone put their fingertips on the record and go back and forth and counterclockwise, I think, “Oh shit! Wow!” It’s kind of cool, Alan.