Cmspic/<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-384722392/stock-photo-learning-to-write-abc.html?src=yW9xzwjv-Y6-is5Vh6jl8Q-1-1">Shutterstock</a>

If pen retailers and state legislators are to be believed, cursive handwriting is facing an existential threat. Since the advent of the Common Core standards—which emphasize keyboard skills over nicely shaped P’s and Q’s—it’s been common knowledge for years that teachers are abandoning cursive in droves, spending classroom time instead on new technology and typing.

But lately, fancy handwriting is having somewhat of a comeback. Louisiana’s governor signed a law in June requiring cursive instruction all the way through grade 12. Mississippi’s education department recently added script to its standards. And starting this school year, third graders in Alabama are required to write legibly in cursive under the newly passed Lexi’s Law. State Rep. Dickie Drake named the Alabama bill after his granddaughter, who told him when she was in first grade that she wanted to learn “real writing.”

The jury is still out on whether learning script, not just print, improves children’s cognition. (There’s little proof to date that it does.) Meanwhile, scientists are inching closer to handwriting’s true existential threat: a mind-reading machine that turns thoughts into written language via a “brain to text” interface. Here’s a primer on how the technology and culture of handwriting has evolved over time.

- 3200 B.C.

-

With stylus and clay tablets, ancient Mesopotamians create abstract symbols to represent syllables of their spoken language.

- 600s

-

Quill pens and parchment paper take hold in Europe. Drippy ink discourages pen lifting, hence cursive.

- 1440s

-

Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press forces scribes to pivot to teaching penmanship.

- c. 1712

-

A popular copybook by George Bickham teaches farmers and merchants to write in a “round” hand. Gentlemen of the era employ an italic script, while accomplished women practice “ladies’ roman.” (In general, only fairly well-off white males are taught to write.)

- 1740

-

South Carolina’s Negro Act makes it a crime to teach slaves to write: “Suffering them to be employed in writing may be attended with great inconveniences.” Other colonies (and later, states) follow suit.

- 1776

-

John Hancock’s “John Hancock” appears prominently on the Declaration of Independence.

- 1848

-

Educator Platt Rogers Spencer urges pupils to contemplate nature’s curves while learning his ornate script, soon to be the hand of choice for merchants (including Ford and Coca-Cola) and schools in most states.

- 1865

-

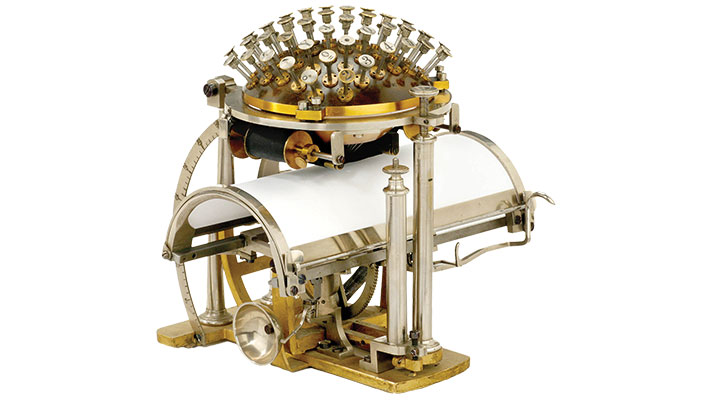

Denmark’s Rasmus Malling-Hansen introduces the first commercial typewriter, the Hansen Writing Ball.

Malling-Hansen Society

Malling-Hansen Society - 1880

-

Alonzo Cross’ patented “stylographic pen” holds its own ink.

- 1888

-

Irish immigrant John Robert Gregg invents a shorthand method that will eventually be taught in countless US high schools.

- 1894

-

With handwriting under threat by typewriters, Austin Palmer introduces a smaller, faster writing style, taught via militaristic “drills.” His 1912 textbook on the Palmer Method sells more than 1 million copies. (Spencerian script is history.)

- 1904

-

French psychologist Alfred Binet popularizes handwriting analysis as a window into the writer’s traits. He goes on to invent the IQ test.

- 1913

-

Congress greenlights the use of handwriting as forensic evidence in court.

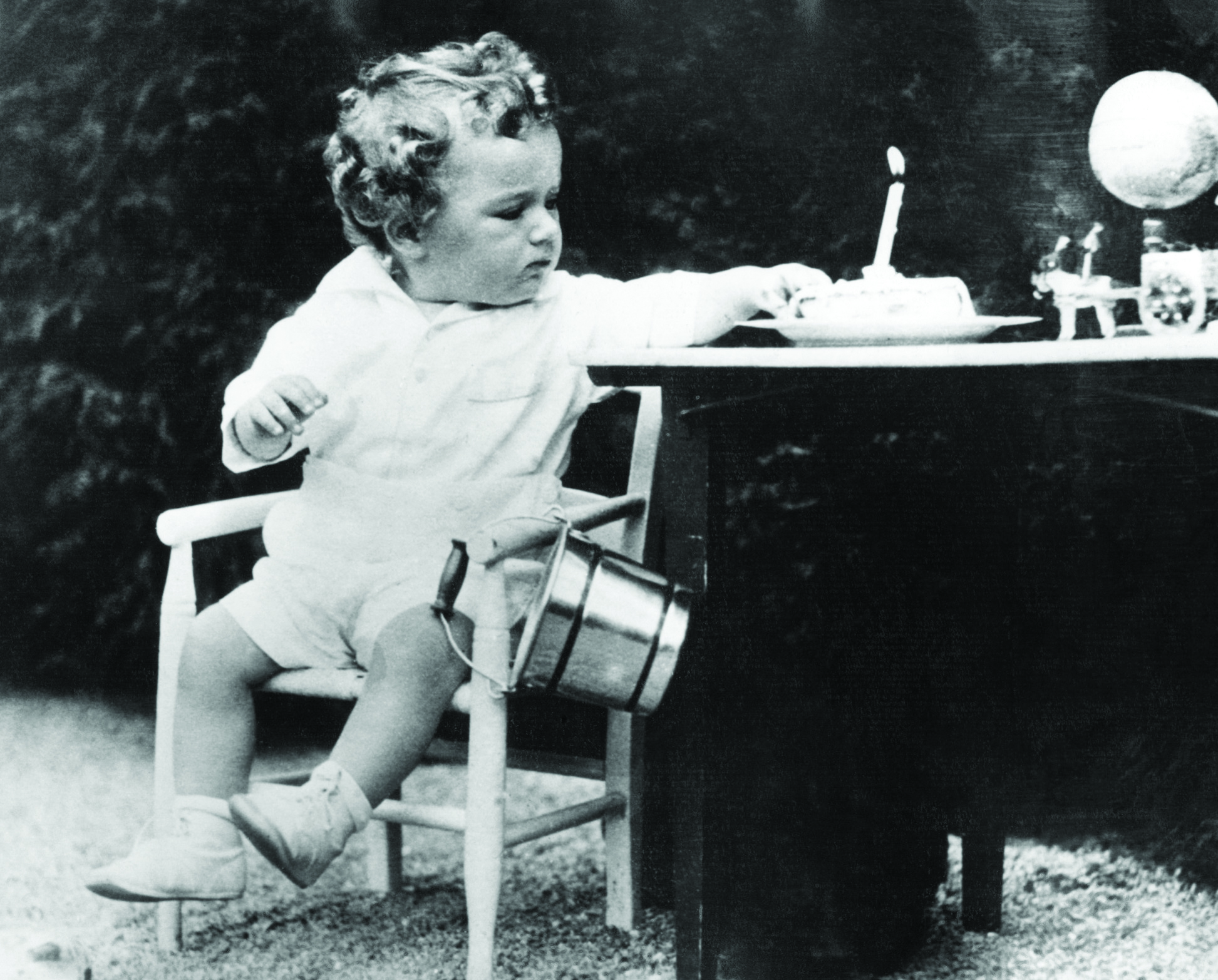

- 1935

-

STF/AFP/Getty

STF/AFP/GettyThe man convicted (and later executed) based on ransom notes for kidnapping the Lindbergh baby laments, “Dat handwriting is the worstest thing against me.”

- 1944

-

László József Bíró markets the first ballpoint pen.

- 1958

-

The Bic ballpoint hits US stores, turning pens—once luxury goods—into a cheap commodity.

- 1961

-

The signature of US Treasurer Elizabeth Rudel Smith on paper currency invites public scorn: Her “t”s are “crossed belatedly, like a feminine afterthought,” snarks a Chicago Tribune writer. The New York Times seizes on the occasion to bemoan the “lost art of handwriting.”

- c.1964

-

From a Louisiana poll test: “Write every other word in this first line and print every third word in same line (original type smaller and first line ended at comma) but capitalize the fifth word that you write.”

- 1977

-

A pen makers’ trade group launches National Handwriting Day even as PC makers including Apple and Commodore begin selling the computer keyboards that presage handwriting’s slow, inevitable decline.

- 1984

-

The National Council of Teachers of English condemns the practice of making naughty kids write lines, because it “causes students to dislike an activity necessary to their intellectual development and career success.”

Fox

Fox - 1996

-

Researchers claim they’ve debunked the “conventional wisdom” that doctors have worse handwriting than other health professionals do.

- 2000

-

Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles urges “handwriting-challenged” MDs to take a penmanship class, even as a key medical journal blasts handwritten case notes as “a dinosaur long overdue for extinction.”

- 2001

-

First-class mail usage hits its peak—only to plummet 40 percent by 2015.

- 2010

-

Common Core standards, soon to be adopted by most states, emphasize early typing skills but make no mention of cursive. Parents and educators flip out. “They’re not teaching cursive writing,” conservative TV host Glenn Beck thunders, “because the easiest way to make somebody a slave is dumb them down.”

- 2012

-

Scientists find that the brains of preliterate kids respond like a reader’s brain when they write their ABCs, but not when they type or trace the letters; another research team reports that college students who transcribed lectures on their laptops recalled more information than those who took notes by hand.

- 2014

-

Bic launches a “Fight For Your Write” campaign—”because writing makes us all awesome!”

- 2016

- Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama mandate instruction of handwriting in public schools. Without it, supporters argue, kids wouldn’t be able to sign their names or read the Constitution. Over at Motherboard, Kaleigh Rogers counters that cursive needs to “join its former companion—the quill and inkwell—in the annals of history where it belongs.”