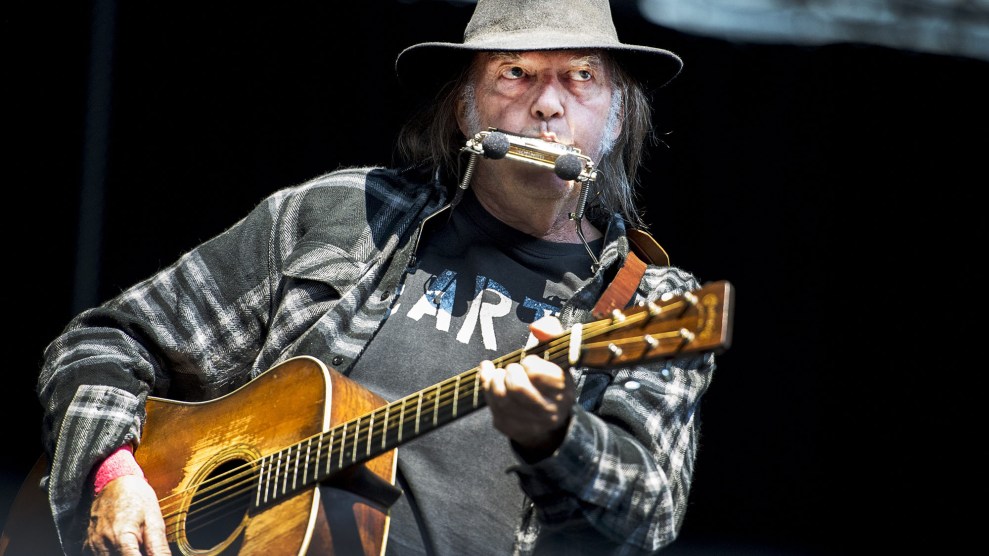

Neil Young performs in Dalhalla, Sweden, in July 2016.Ibl/Rex Shutterstock/ZUMA

Legendary rocker Neil Young continues to add to his 50-plus-year recording career with his just-released studio album Peace Trail. A shrewd collection of new songs, written and recorded quickly this past summer, the album is one of immediacy, with kinetic playing from a spare crew of Jim Keltner on drums and Paul Bushnell on bass. With bits of processed vocals added to the folk-rock core, and an amplified harmonica that sounds like Little Walter after a Marvel-esque dose of radiation, Young employs strategies meant to throw the whole thing off kilter and make you listen closer.

The songs cover the things on the singer’s mind right now, both within—old dreams broken and those newly forming—and in the world around him: Standing Rock, xenophobia, immigration, and technology. For an artist at 71, it’s beautifully charged, invigorated, and present work. While the call is urgent, Young doesn’t beat you over the head with the message so much as inject you with it. I spoke with Young over the phone while he was at his home in Colorado.

Mother Jones: Overall, it feels very much like this is an album about being present with things happening in the world, as well as with your own feelings. Tell us a bit about the emergence of this record.

Neil Young: I started writing “Peace Trail” here in Colorado, then I went back to California. I had a few other tunes going around in my head, so I had a couple of them finished after a few days and then I wanted to go into the studio. I like to go in right away as soon as I have things. I called the guys from Promise of the Real, whom I’ve been playing with, and they were all on the road. Right after I hung up the phone, I wrote another song and started writing another, and I’m going, “Hey, I can’t wait. I should be doing this now!” My experience tells me that when it’s there, it’s there, and you can’t make it wait. So I got Jimmy Keltner and Paul Bushnell, two good guys, and went in and did this record.

MJ: Both of those guys, obviously, are experienced session musicians. Did you relate specific things to them or did you all kind of feel things out together?

NY: I would play all the parts of the song, show them the way it went together. Then I’d basically break down an arrangement—I wouldn’t plan endings or beginnings—so they knew everything that was going on. I had the lyrics on a prompter so that I could remember everything I’d written, and I was able to just get into the groove and play with them. Most cases it’s Take 1 or Take 2 on that record. I think “Peace Trail” is one of the exceptions, where it’s a later take. It just happened really quickly. It’s the way I like to work for these kinds of songs. It was the right time of the month; everything was looking good.

MJ: I felt like the immediacy of the playing on this particular album, and some of the disruptive things you introduce, like the sound processing on the harmonica and vocals in places, make the listener pay more attention.

NY: The songs were written to have a certain simple form. Everything is minimal, and if it’s over, it’s over. We’re abrupt with things: in and out. Especially if it’s an overdub—it’s gone. It does something that’s not real. It’s not trying to be like it was there. I think the ultimate result of it is you can get inside the record. I do one take; I never overdubbed twice. I know there’s stuff that isn’t perfect, but it doesn’t matter: Nothing is perfect, and there is a magic there that is undeniable because of the fact that we don’t care about those things. We’re really more interested in what we’re saying than how we’re saying it.

MJ: On the song “Peace Trail,” you express a commitment to moving forward and a sense of optimism with the refrain, “Something new is growing.” Did the November election alter that outlook?

NY: Not really. I still feel the same about everything in there. There’s nothing I said that I would change or make different now. I’ve already gotten into the next record, so I started that on the 6th of November.

MJ: In the song “Can’t Stop Workin’,” you sing that work is “bad for the body but good for the soul.” What’s hard for you?

NY: I think it’s the constant work; performing and traveling. It gets to be a bit of a strain. But if you pace yourself, which I’ve managed to do, you can go pretty well. And now I’m at a point where I decided I’m going to be in the studio for a while, at least until I finish this record I’m working on now. I should have two, three, four of the sessions that I had that were similar to the sessions for Peace Trail before I have a complete record. But I’m off to a good start and it may happen faster. Who knows?

MJ: I had an unsettling feeling that the purpose of my own work as an artist should maybe change after this election, but I’m unsure how. You’ve lived through really turbulent times and have written some very powerful protest songs—”Ohio” and “Southern Man,” for example. So how do you view the responsibilities of being an artist in the years to come?

NY: This time is very similar to the ’60s, as far as I can tell. The artists always reflect the times, so there’s a lot to think about, a lot of unknowns, a lot of things that are describable. This is the closest I’ve seen to the kind of ambience that made the ’60s happen. It’s not about the artist having a responsibility to do anything. They have to be artists and express themselves and everything will work out fine. It’s all going to be great. The youth of this country are not behind what is going on. We all know that. If you looked at a [political] map of the United States 25 and under, it’s all-revealing. It’s a unified map.

MJ: What scares me is this rift in our understanding of one another. You have viewpoints so far apart, so colored by anger and frustration, that it’s very hard to find common ground. Do you have thoughts for how we might connect?

NY: It’s gonna happen. We had the Vietnam War in the ’60s, and there was a draft. The students didn’t believe in it, and it unified them. That brought the people together and made the ’60s like they were. The youth were very unified against the status quo—against the old line and the new old line. It’s the same exact thing today. Social media and young people, art, music, all communications make this one of the most active times for activism. It will be a time of change.

MJ: Speaking of activism, there’s your new song “Indian Giver,” about Standing Rock. What’s your view on the standoff?

NY: It’s injustice. It’s wrong. [The pipeline companies] didn’t get the permission. They didn’t do the things they should have done in the first place. They tried to just bully their way through there and they got stopped. But they’re not really stopping.

MJ: It’s become a new point of reckoning in the history of how Native Americans are treated.

NY: Five hundred years later we’re still doing it. This is a moment where we’re either going to reaffirm that’s what we do, that’s who we are, or we’re going to start moving toward change. A change won’t come easy, because there’s a lot of big money that doesn’t care about any of this. Standing Rock is the beginning of something. It’s a moment in history. We really have to grab it and go with it. We may only be halfway through the actual “Standing Rock” part, [but] it’s more than that—it’s the lessons of Standing Rock, of what you can do. How much can you make change happen? How long can you slow things down? How much attention can you bring to things that are unjust, unfair, in many cases illegal? Just exposing it, that’s the job of the social media, the musicians, the people who care, the real protectors around the world. They don’t have to be at Standing Rock. They just have to say they’re with the people at Standing Rock, and tell other people that what’s going on there is wrong. Learn about it. See what happened. See what they actually did. You won’t see it on corporate media, you have to go to social media.

MJ: So, it looks like we’re out of time here. Is there anything else you’d like to say?

NY: We love Mother Jones. That’d be the last thing to say.

MJ: We love you, too.