James Perry/UPPA/ZUMA Press

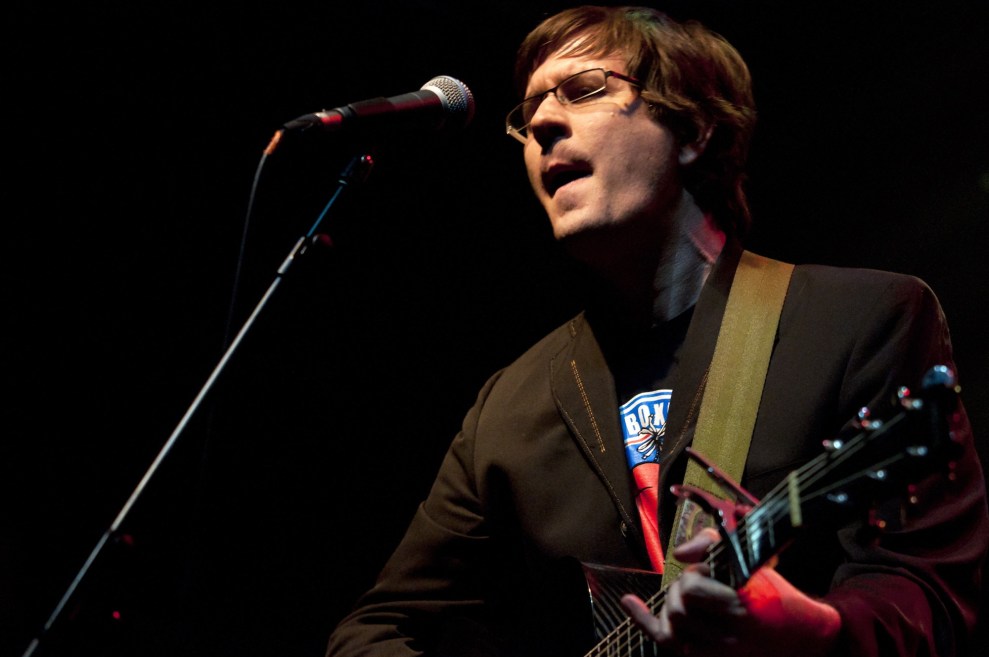

Cult indie-folk band the Mountain Goats is known for having fans that are rabidly devoted—and you’d almost have to be like that just to keep up. Led by John Darnielle—a charmingly nerdy 49-year-old songwriter whose professed admirers include Stephen Colbert, and whom Rolling Stone recently dubbed rock’s “best storyteller”—the Goats have put out 15 albums since 1994, using simple chord structures as a framework for Darnielle’s complex lyrical narratives. Fans have even petitioned to make him America’s Poet Laureate, so maybe it’s no surprise that Darnielle recently stumbled into literary success as well.

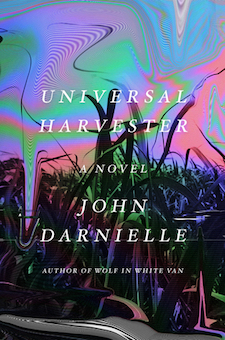

His debut novel, Wolf in White Van, about a reclusive, disfigured game designer who seeks refuge in a role-playing game, was a 2014 National Book Award finalist. Out February 7, Darnielle’s latest, an enchanting horror mystery called Universal Harvester, follows a video store clerk in small-town Iowa whose customers begin complaining of disturbing footage spliced into their rented VHS tapes. (The paperback review copy came sheathed in a plastic VHS clamshell.) When he’s not writing something, Darnielle, raised in a progressive activist household, is out fighting for reproductive justice—serving, for instance, on the board of the National Abortion Rights Action League and performing in support of Planned Parenthood.

Mother Jones: So you’re this celebrated songwriter and touring musician, and one morning you wake up as a novelist?

John Darnielle: It was much slower than that! An editor from Continuum asked me how come I hadn’t pitched to “33 1/3” [a series of books about individual LPs]. I pitched Black Sabbath’s Master of Reality. He liked it, so I wrote it. The critique was housed in this fictional narrative, the longest long-form narrative I’d ever attempted—at least since I wrote a very long poem cycle in the late ’80s. An album you write a bunch of songs and put them together, but with this, the focus it required was exhilarating. I submitted the manuscript, and while waiting to hear back I just started writing something else—I ended up writing what became the last chapter of Wolf in White Van. It was just something to do. A lot of good work sort of starts in idleness and becomes labor. Labor for a lot of people has a negative connotation. But not for me. I always want to be working.

MJ: And you got a National Book Award nomination straight out of the gate!

JD: I’m still kind of processing that. I thought that people wouldn’t hate it, but really, I was in shock. That happened two days after it got published! My editor calls me, “Hey, you’re not gonna believe this.” [Laughs.]

MJ: So, many successful first-time authors struggle with their second novel.

JD: It’s both easier and harder. The easier part is you know you can do it, whereas at a certain point on Wolf in White Van I’m sitting on the floor in the hallway with the manuscript all over the place, cutting up with scissors, trying to figure out what went where. There was a point where I was like, “This is going to be a mess. I’ll never put it get it back together.” If I hadn’t done it out in physical space, it would’ve never gotten finished. The second one, you know well enough to be planning ahead. A lot of the time with Wolf, I would find out what was going to happen as I wrote the sentence: click click click click…Oh! He went to a hospital! You can ad-lib a song. A novel is a performance you have to plan.

MJ: In the new book, as we often see in your music, there’s this horror motif.

JD: When I was a kid, I was a big science fiction fan, but current horror books were harder to get your hands on. You’d get, you know, Poe and Lovecraft. So there was this zine called Whispers. They would publish things by Robert Aikman, Manly Wade Wellmann, and Dennis Etchison, big names in a very small pond. Whispers was very hard to find, but it was really cool. Aikman would write horror stories that weren’t gore, they weren’t slashers, and they weren’t monster stories either. He called them ghost stories. The main thing about them was the vibe. It was really disquieting. He wanted to sketch the scene so that you could see it and know the characters and get a feel for the motion—and then ask yourself why and not get a final answer. Leave something that itches. I loved that! Etchison would write stories that were just punch lines at the end. You wouldn’t realize something horrific was happening until the last paragraph.

MJ: So what scares you most?

JD: The possibility of disaster remains horrific to me. Like when you know everything’s about to go wrong in a way that’s not controllable or knowable. What’s scary is the unknown, the stuff you can’t put your finger on. Hauntings are also scary—the notion that there are things from the past that render, that you can’t wash out, that you can’t be free of. The notion of the mark—the mark of Cain—is scary. Stuff clinging to you is scary.

MJ: Did you ever work in a video store?

JD: I worked the AV counter at the Roland Heights public library in the ’80s.

MJ: Did people ever record weird stuff on the tapes?

JD: No, I made that up. My best story from the library was the time a couple asked for a recommendation, and I recommended Raising Arizona and they absolutely hated it. They came back hungry for blood. I was on my lunch break and my boss came out and said, “Hey kid, you need to come talk to these people. They totally hate Arizona.” And he said, “Arizona‘s a dog; nobody gets that movie.” I said, “What’re you talking about! All my friends love that movie.” [Laughs.]

MJ: Was it your idea to package the book in a VHS case?

JD: No. This is the funny thing about me. People think John just comes up with all the ideas. I’m honored. People think I have a big old brain, but actually I am the sum of the people I work with. I do a few things pretty well. I write good songs, I hope I write good books, and I’m a pretty bitchin’ performer, I will say—you come to a Mountain Goats show and you’re gonna have a good time. But I consider myself a prep cook. The stuff I do is indispensable to the meal, but it’s not the whole meal.

MJ: You write so many songs. Do you ever get bored of it?

JD: Nah. People don’t tend to notice, but in the past 10 years especially there’s been a lot of growth in how I write songs and what goes into them. You can listen to Mountain Goats from 1991 to 2007 and never hear a seventh chord. In 2007 or 2008, I started working on the piano to grow as a songwriter. I started throwing major sevens in and sixes and more interesting stuff. I still write in 4/4 [time]. Maybe not the next hurdle, but one I want to meet in a couple years, is writing something in three or in six.

MJ: Wait, you’re going to turn the Mountain Goats into math rock?

JD: Well, six is not that complicated, but 13—I’d like to write something in 13!

MJ: You officially retired your song “Going to Georgia.” Have you retired others?

JD: Yeah, I think that’s pretty natural. I suspect by the time the Beatles were writing the White Album, they didn’t go, “‘I Wanna Hold Your Hand!’ I wanna play that!” It’s like if somebody asked you to put on the clothes you wore in high school. Well, no. No!

MJ: What was it like growing up in this intensely pro-choice household?

JD: It was exciting, insofar as I was thinking about things that few of my peers were. Young people like to feel self-righteous, like they’re on the right side of things.

MJ: In recent years, abortion rights have come under serious assault.

JD: If you’re working at the very local level and there are nine of you and six of the other people, you can strong-arm them. The anti-choice forces stole that tactic from the left! They’ve learned that if you act locally, you can get stuff on the books that will take forever to undo. It’s the same with redistricting. It’s hard to get people from far away to give a shit. That’s the issue! It’s easy to follow national politics and weigh in on social media, but if I’m tweeting stuff about Chatham County, no one cares. All you can do is wait until they make a move that’s unconstitutional, and then you have to sue, and you appeal—that’s how it works.

MJ: You’re based in Durham, North Carolina, these days?

JD: Yessir. We’re actually right next door to Wade County, where the first targeted regulation of abortion provider (TRAP) laws [were enacted]. They can’t outlaw abortion, so they say, “Well, you can have an abortion, but the operating table has to be a Möbius strip, and the public restroom has to be 1,000 yards from the operating table.” It’s so playground! It’s: “Cross this line and I’m gonna punch you in the face,” and then they draw the line in back of you.

MJ: North Carolina recently has been on the vanguard of being against trans rights and eroding voting rights and so on.

JD: North Carolina was on the vanguard of being for those things, and that’s why we’re seeing this pushback. The conservatives noticed that there had been a lot of progress and they tried to tamp it down. Conservative forces in the South have a lot of power—almost dynastic—dating back many years. Our [former] governor [Pat McCrory] was supposed to be a moderate, but he found himself beholden to people who have much more draconian ideas. I think he assumed this stuff flew under the radar.

MJ: The Black Lives Matter movement in Charlotte seems pretty robust.

JD: Durham was gonna vote Democrat regardless of whether the Republicans nominated this madman—it’s a very blue county. Charlotte—things are a little different. But over the past 40 years, the tradition of Southern progressivism has been somewhat successfully erased by right-wing revisionist historians. The South actually has a very strong tradition of activism. The civil rights movement came from down here! It was black activists demanding that their voices be heard. People say these are red states. No they’re not! They’re hotbeds of progressivism that have been legislated against and redistricted out of existence. The fighting spirit remains in the voice of the people down here.

MJ: Are you tempted to infuse your songs and books with your politics?

JD: No. I have a hunger for justice, but art is a place I’ve always enjoyed being able to be free—to live in worlds that you don’t have to be thinking about that all the time. I don’t see myself writing Upton Sinclair books. My books are to entertain, although to me, entertainment is to make you feel sadness or to get in touch with your own pain—or fear, or to remember somebody who has gone missing from your life. That’s my calling. There are real teachers out there; I don’t pretend to have their mantle.

MJ: Are there any writers you’ve tried to emulate?

JD: There are stylists I really love. I’m a huge Joan Didion fan—if I wrote something that she might like, then I’d feel very proud. I want the action to move as quickly as it does in A Book of Common Prayer, where one thing bonks right into another very quickly, but I want the effect to be a little more velvety—simple language that has lush effects.

MJ: Had you ever written fiction prior to Wolf?

JD: I wrote short stories when I was a teenager, but they weren’t any good and I kinda knew it. I was 14 or 15 when I discovered poetry, and I pretty much stopped writing prose until Master of Reality. I did a lot of music criticism. I don’t think much of it was any good. I think I wanted to show off a lot when I was younger. Now I just want people to enjoy the story. If it were possible to publish anonymously, that would be awesome.

MJ: A lot of your fans seem to know your entire catalog. They sing along at shows and shout out constant requests. What does that feel like?

JD: It’s a a huge honor. I try not to dwell on it, because anything that might lead to me being too egocentric is not healthy. I’ll look at them and try to have a moment with them, but I hope it’s more of a shared experience than a didactic one.

MJ: Do the requests get annoying?

JD: Generally no. A good show—and this is on the band as much as on the audience—people will get a sense of the rhythm, so they won’t yell out a request after some song where everyone has gotten real sad together. That would be unkind. But I don’t really have any position to complain about my job. Yeah, every job has its moments like, “Ah, you know, it’s Wednesday.” But I’m blessed. I love my work.