I was never that much of a history buff, so it’s pretty rare for me to sit down and watch a documentary about a war that ended before my mom was born. But I’m rethinking my slacker ways after watching The Great War, a captivating new series premiering April 10 on PBS’ American Experience.

The history of this nation’s involvement in World War I is as fascinating as it is unsettling. The Great War also was our global coming of age, the beginning of America’s transformation into a nation deeply engaged in world affairs and conflicts. Perhaps what struck me most about the three-part, six-hour series was the familiarity of so many of its themes—a sense of déjà vu that left me feeling like even those of us who know our history are doomed to repeat it.

Here are 10 big takeaways from the series to accompany this exclusive clip (above) about the wartime crackdown on dissent.

1. America was as polarized a century ago as it is today. In 1917, the country was split over race relations, voting rights, domestic politics, our place in the world, and whether we should be fighting foreign wars at all.

2. The “great” war was so not great. Like all big conflicts, World War I had its inspiring tales of duty, bravery, and heroism, but the primary narrative was one of staggering deprivation and devastation. By the time America came in, some 15 million soldiers and civilians were already dead. (The 1918 flu pandemic, made worse by the war, would kill millions more.) Beyond the bullets and shells, the Germans introduced frightening new weapons including mustard gas, which was soon adopted by the Allies. During the Meuse-Argonne offensive, US soldiers fighting the Germans lost an average of 550 men per day for 47 straight days. Three times that many were wounded. “It was, and remains,” notes one commentator, “the bloodiest battle America has ever been involved in.” But the longest conflict we’ve ever been involved in is still happening—over in Afghanistan.

3. Immigrants were scapegoated. Sound familiar? With Americans being shipped overseas to backstop French and British forces against the Kaiser’s army, German Americans became the bad guys at home. They were forced to register with the federal government. German language and songs were banned from schools. There were stein-smashing events, and citizens were encouraged to report those they suspected of disloyalty. Anyone deemed pro-German might be beaten, tarred and feathered, hauled to an internment camp, or even lynched. Now we have anti-Muslim travel orders, rising hate crimes, and an anti-immigrant president who supports the notion of a Muslim registry—during the campaign, a Trump surrogate cited internment camps as a precedent. This is a slippery slope, people.

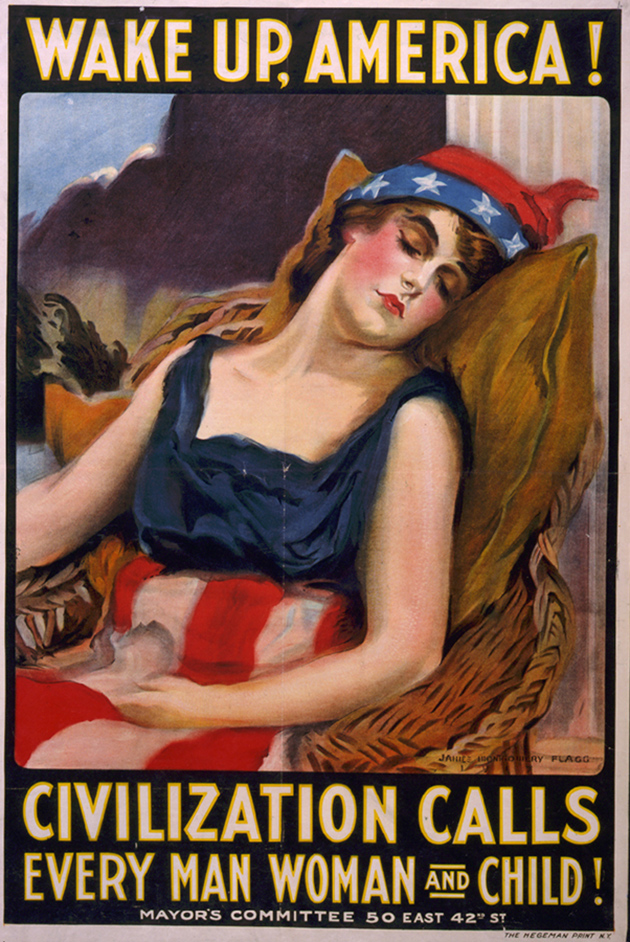

4. You were either with us or against us. Remember how the politicians who refused to fall in line with George W. Bush’s post-9/11 crackdown on civil liberties (and his move to invade Iraq) were attacked for giving aid and comfort to the enemy. Rewind to 1917: At first reluctant to enter the war, President Woodrow Wilson went all in, brooking no dissent from the public. Conformity was enforced by means of federally funded propaganda, as well as vigilante groups that, with the blessing of the Department of Justice, conducted “slacker raids.” Police, too, conducted mass roundups, locking up draft evaders, conscientious objectors, and war critics such as socialist leader Eugene Debs. Hutterite religious objectors were tortured (some to death) at Leavenworth military prison.

5. Laws were passed to justify repression. With today’s Republican lawmakers proposing harsh penalties for peaceful protest activities such as blocking traffic, it’s instructive to recall the Espionage and Sedition acts that Congress passed in 1917 and 1918 at the urging of President Wilson. (One of the film’s featured historians, Michael Kazin, calls Wilson “both the great Democrat and one of the most oppressive figures in American history.”) Used to prosecute more than 2,000 Americans, “these two acts really become tools to shut up people who refuse to be quiet about their opposition to the war, especially left-wing organizations—socialists, the IWW [International Workers of the World],” historian Jennifer Keene explains. Simply griping to a colleague about food rationing might get a man locked up. “For every prosecution,” adds historian Christopher Capozzola, “there may be tens, hundreds, thousands of ‘friendly’ visits by government agents warning someone not to say what they said or write what they wrote.”

6. World War I spawned a huge propaganda machine. Wilson enlisted marketing guru George Creel to sell the war and made him the head of a new federal Committee on Public Information. Creel was masterful in controlling the narrative of the conflict at home and spreading the view that if you weren’t actively down with the war effort, then you were disloyal. Years later, the administration of George H.W. Bush relied on PR firms to gin up public support for Operation Desert Storm. You might recall the fabricated story of Iraqi troops ripping babies from their incubators at a Kuwait hospital and leaving them to die—brought to you by a Kuwaiti government front group that hired companies such as Hill & Knowlton to make its case for America to go after Saddam.

7. America betrayed her black soldiers. The documentary, whose commentators include several black historians, does a fabulous job of showing how the war was transformative for African American soldiers. Handed over to fight hellish trench battles under French command, they were treated, if not as equals, then at least as worthy comrades by their white French counterparts. The returning veterans were no longer content to accept the racist status quo in America; hundreds were lynched for resisting white supremacy. The “red summer” of 1919 was “a wave of racial violence unparalleled in United States history,” notes historian Chad Williams. “It was a horrific statement about how the aspirations of African Americans were going to be met with violent resistance from white people.” Thousands of blacks wrote to the White House begging for help, but they were given the cold shoulder. President Wilson, at once a global visionary and a small-minded bigot, refused to acknowledge the slaughter, and America remained as violently racist as it ever was. But the new perspective and sense of entitlement among black veterans planted seeds for a civil rights movement yet to come. America, of course, is still pretty darn racist.

8. The war was a turning point for women’s voting rights. The suffragists of the time, led by Alice Paul, were deft at turning Wilson’s war rhetoric against him: Even as young Americans died to “make the world safe for democracy,” they said, Wilson was stifling democracy at home. Anti-government protests had all but evaporated once America declared war, but Paul and others continued their daily vigil outside the White House gates. Even after Wilson had the women locked up, they continued to make him look bad by launching a hunger strike. Wilson eventually capitulated. Congress approved the 19th Amendment in 1919—the states ratified it in 1920. (Now it’s people of color who are stuck fighting—yet again—to protect their voting rights.)

9. Petty bipartisan squabbling ruined everything. After the immense effort of negotiating the terms of peace in Europe and selling the treaty to the American public, the president let his petty rivalry with Republican Henry Cabot Lodge doom the treaty’s ratification by the Senate. What if Wilson had let the pact proceed with Lodge’s inconsequential amendments attached? Or what if he’d brought the Republican leader along with him to Paris when he negotiated the treaty? What if America had ratified the treaty and stayed intimately involved in the postwar order? “Just what if?” asks historian Margaret MacMillan. Her implication is clear: World War II might never have happened.

10. Hillary Clinton actually would have been our second female president. Shortly after Congress nixed Wilson’s hard-fought treaty, the president suffered a massive stroke. His inner circle covered up the severity of his condition for a year and a half, while first lady Edith Wilson essentially served as a covert chief executive: “A handful of people in the White House,” says Wilson biographer A. Scott Berg, “engaged in the greatest conspiracy in American history.” Yet.