Aircraft workers during WWII.Bransby, David/Library of Congress

Mothers have always worked in this country, whether out of desire or necessity. But America’s relationship with these employed moms has been fraught from the start. In 1873, a Harvard medical professor claimed that higher education would make young women infertile. During the 1950s, writers, psychiatrists, and psychologists argued that career women had “penis envy,” while John Bowlby’s “attachment theory” was widely misconstrued to mean that moms spending time apart from their kids would cause permanent psychological damage.

Where the emotional appeals haven’t worked, opponents have outright or effectively blocked moms from clocking in by cutting day care programs, firing them for breastfeeding, and refusing them family leave. To this day, the United States remains the only industrialized nation that doesn’t mandate maternity leave.

As many have pointed out, all moms are working moms, regardless of whether they are paid for their work. But as sociologist Arlie Hochschild put it in her book The Second Shift, mothers juggling housework with a day job enjoy a “double burden.” In time for Mother’s Day, here’s a short history of some of America’s most underappreciated employees.

- 1800s

- Women are legally barred from jobs such as lawyering and working underground based on the notion of “separate spheres“—a women’s should be at home with her children.

- 1850

- The popular magazine Godey’s Lady Book touts piety, purity, submissiveness, and domesticity as the traits of “true womanhood,” and notes that women “step out of their own path when they attempt to encroach on the proper masculine pursuits.”

- 1851

- Abolitionist Sojourner Truth points out that Godey’s definition excludes black women, who are often obliged to work outside the home to feed their children. “Ain’t I a woman?” she asks.

- 1869

- A shorthanded Treasury Department hires married women including moms to fill positions vacated by Union soldiers. At war’s end, some widows are allowed to keep their jobs—at half the pay men get.

- 1873

- Harvard Medical School professor Edward Clarke argues that higher education makes women infertile.

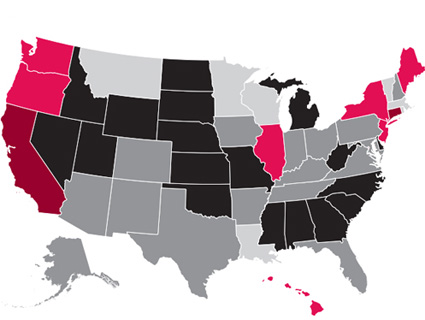

Turn of the 20th Century postcard

Turn of the 20th Century postcard - 1888

- Josephine Jewell Dodge establishes an early nursery school in a New York City slum that is later featured at Chicago’s World Fair. She goes on to start the country’s first national day care organization. Her critics propose an alternative strategy—”mothers’ pensions“—to keep women at home.

- 1930s

- The Depression forces white middle-class moms to look for jobs—the number of married women in the workforce jumps 50 percent—while women of color solicit day labor in so-called slave markets. But “no one should get the idea that Uncle Sam is going to rock the baby to sleep,” the White House declares.

- 1943

- World War II shortages of male workers inspire the first federally funded day care program. But the armistice marks a return to traditional gender attitudes: The day care initiative lapses and career-driven women are described by popular writers as “lost,” “man-hating” or “suffering from penis envy.”

- 1950s

- Employers phase out the “marriage bar“—the legal practice of firing (or not hiring) women who get married. It will be nearly three decades before federal law forbids the boss from firing women for being pregnant.

- 1951

- Psychoanalyst John Bowlby’s “attachment theory” posits that separating a mother from her child causes long-term behavioral difficulties—short separations are fine, he says, but his theory is twisted to make the case that mothers shouldn’t work.

- 1952

- Lucille Ball’s real-life pregnancy is written into an episode of the sitcom I Love Lucy, but the actors are not allowed to use the word “pregnant” on air—too vulgar, says CBS.

- 1963

- Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique gives voice to “the problem that has no name”—the frustrations and disappointments of housewives. Friedan had conceived of her idea as a magazine piece, but no magazine would take it.

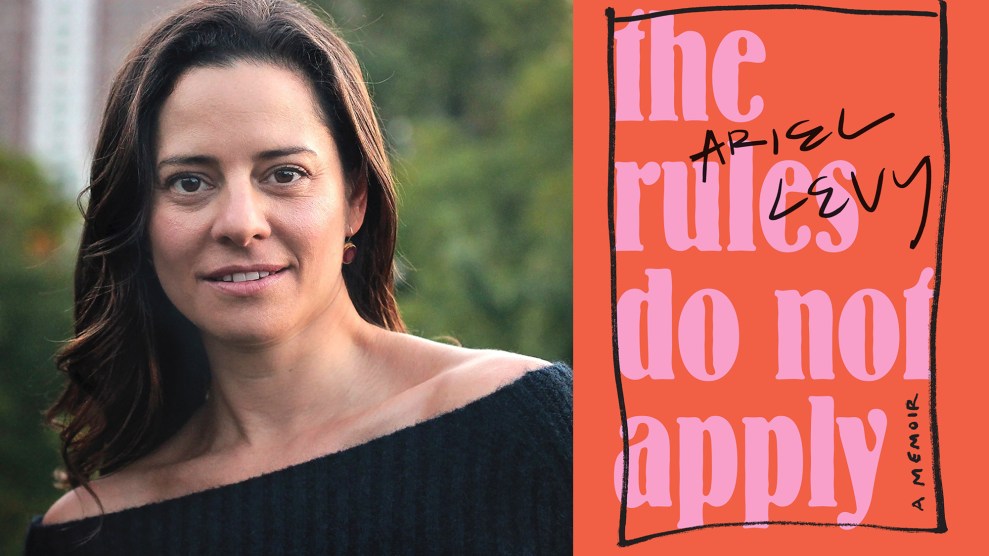

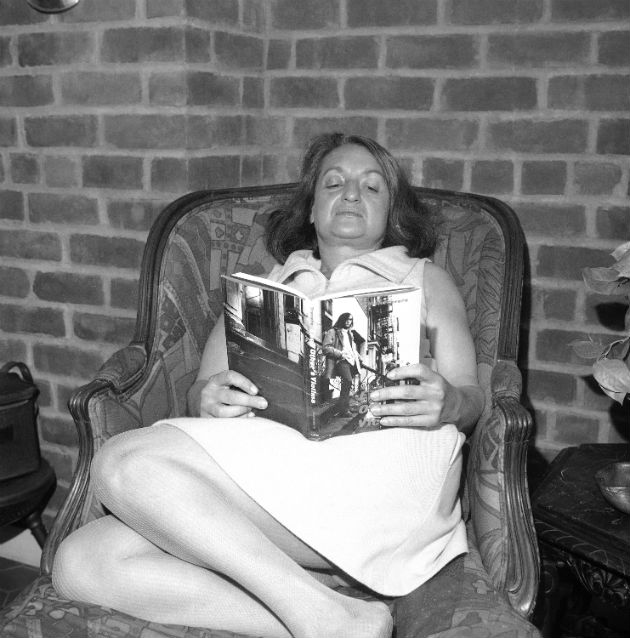

Betty Friedan AP Photo/Anthony Camerano

Betty Friedan AP Photo/Anthony Camerano - 1969

- Under disability laws, five states allow female workers paid maternity leave, while others specifically exclude pregnancy as a temporary disability. A federal family-leave law remains decades away.

- 1970

- “I have no objection of a pediatric or psychiatric nature about women going to work,” writes child-development guru Dr. Benjamin Spock: “What I say is that the children are going to have to be reared, and you ought to have women growing up feeling this is important, womanly work.”

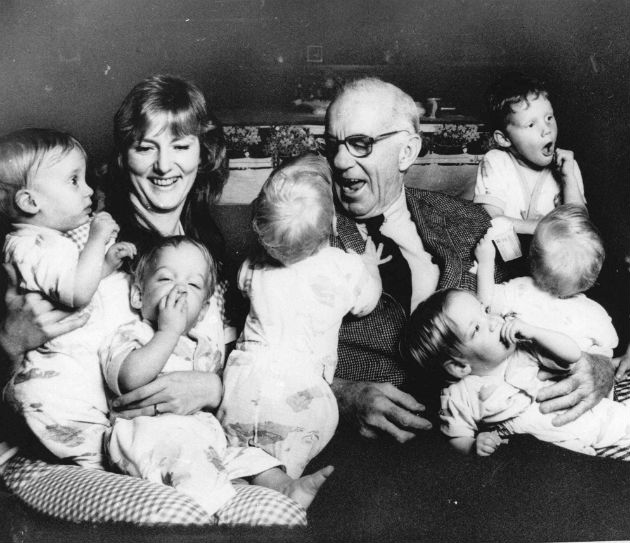

Dr. Spock Associated Press

Dr. Spock Associated Press - 1971

- Congress votes to establish federally funded child care centers nationwide, but President Richard Nixon vetoes the bill, saying it works against “the family-centered approach.”

- 1972

- The Equal Rights Amendment, which outlaws sex discrimination, is attacked by conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly on the grounds that a women’s place is in the home. (The bill flops.) Betty Freidan dubs Schlafly “Aunt Tom.”

- 1978

- An ad for Enjoli perfume croons, “I can put the wash on the line. Feed the kids. Get dressed. Pass out the kisses and get to work by five of nine. ‘Cuz I’m a wooooman!” Congress passes the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, making it illegal to fire a woman for being pregnant—employers must offer her medical benefits equivalent to what other workers get.

- 1979

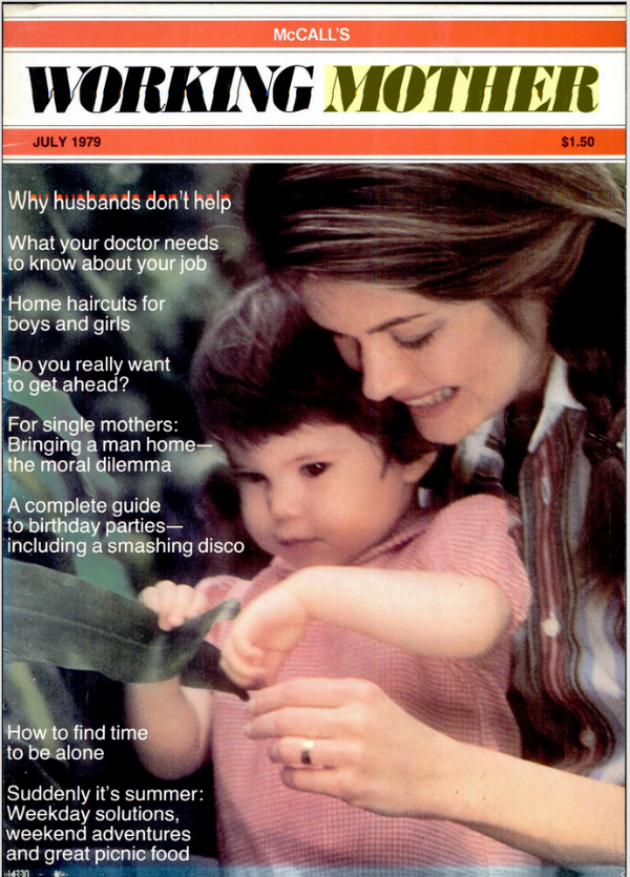

- Working Mother magazine targets America’s 16 million working moms: “We would like to share in your problems, your concerns for your family—and in your pride.” (It’s still around.)

Working Mother magazine

Working Mother magazine - 1989

- In The Second Shift, sociologist Arlie Hochschild describes the “double burden” of mothers juggling housework with a day job. Also Child magazine coins the phrase “mommy wars” to describe tensions between working and stay-at-home mothers.

- 1992

- Vice President Dan Quayle attacks TV show Murphy Brown for “mocking the importance of fathers” after the eponymous character, a working journalist, decides to raise her baby alone.

- 1992

- Asked by reporters about allegations that her husband directed business to her law firm while governor of Arkansas, Hillary Clinton responds, “I suppose I could have stayed home and baked cookies and had teas, but what I decided to do was to fulfill my profession.” Homemakers are furious.

John Sykes/Liason

John Sykes/Liason - 1993

- The Family Medical Leave Act guarantees maternity leave—but it’s unpaid, and more than half of working women are excluded thanks to exceptions for small businesses and part-timers

- 1994

- Asked how he feels about then-wife Marla Maples (top) working, Donald Trump tells ABC, “I have days where I think it’s great. And then I have days where, if I come home—and I don’t want to sound too much like a chauvinist—but when I come home and dinner’s not ready, I go through the roof.”

- 1996

- Amid backlash against mythical “welfare queens,” President Bill Clinton overhauls the system, forcing single mothers to get a job within two years or lose their federal benefits.

- 1997

- Future Indiana Gov. Mike Pence argues in an op-ed that “day care kids get the short end of the emotional stick” and that children with two working parents suffer “stunted emotional growth.” Also the Breastfeeding Promotion Act, a bill to end discrimination against nursing moms and make companies give women a place they can pump breast milk, dies in committee.

- 1999

-

The proportion of moms staying at home rather than working hits a low point of 23 percent. (By 2012, it’s up to 29 percent.)

- 2003

- The New York Times Magazine describes the “opt-out revolution”—highly educated women scaling back their careers to stay home with their kids.

- 2008

- The VP nomination of Sarah Palin, a mother of five, renews debate over work-life balance. “You can juggle a BlackBerry and a breast pump in a lot of jobs, but not in the vice presidency,” one Obama supporter tells the New York Times.

- 2009

- Modern Family premieres on ABC—none of its fictional moms have jobs. Also a Texas woman is fired for asking her boss to let her pump breast milk at work. A (male) federal judge rules the firing is permissible because “lactation is not pregnancy, childbirth, or a related medical condition” protected by law.

- 2010

- The Affordable Care Act mandates work breaks and a private space for new moms to pump breast milk.

- April 2012

- Mitt Romney defends his homemaker wife: “I happen to believe that all moms are working moms.” Yet earlier, talking about the welfare-work requirements Massachusetts enacted while he was governor, Romney said that even moms with two-year-olds “need to go to work…I want the individuals to have the dignity of work.'”

- July 2012

- Anne Marie Slaughter argues in The Atlantic that women cannot, in fact, “have it all”—kids and a fulfilling career. The problem, she writes, isn’t an “ambition gap,” but rather that America’s workplace culture still doesn’t value families.

- Sept. 2012

- “At the end of the day,” Michelle Obama tells the Democratic National Convention crowd, “My most important title is still ‘mom-in-chief.'”

- 2013

- In her best-selling book, Facebook bigwig Sheryl Sandberg exhorts women to “lean in” at work. Cultural critic bell hooks eviscerates the book as “faux feminism…brought to us by a corporate executive who does not recognize the needs of pregnant women until it’s happening to her.”

- 2014

- Apple and Facebook offer to freeze employees’ eggs in what critics call a cynical bid to delay childbearing. Actress Gwyneth Paltrow, meanwhile, claims she has it harder than office moms who “can come home in the evening.” Retorts a New York Post columnist, “Thank God I don’t make millions filming one movie per year.”

- 2016

- America remains the only industrialized nation that doesn’t mandate paid maternity leave—only 14 percent of working moms can get it through their employers. In a September interview, Ivanka Trump brags to Cosmopolitan about her dad’s maternity-leave plan, calling him “a great advocate for women in the workforce.” But it turns out many Trump Hotels, including Mar-a-Lago, don’t offer paid maternity leave.

Ivanka Trump and Donald Trump at the Republican National Convention Jim Watson/AFP/Getty Images

Ivanka Trump and Donald Trump at the Republican National Convention Jim Watson/AFP/Getty Images - 2017

- President Trump proposes a child care plan and asks Congress to “help ensure new parents have paid family leave.” But a Tax Policy Center analysis concludes that 70 percent of the plan’s benefits would go to families making $100,000 or more. “The devil,” the ACLU notes, “is in the details“—the plan applies only to married birth mothers, making it “as inadequate as it is discriminatory.”