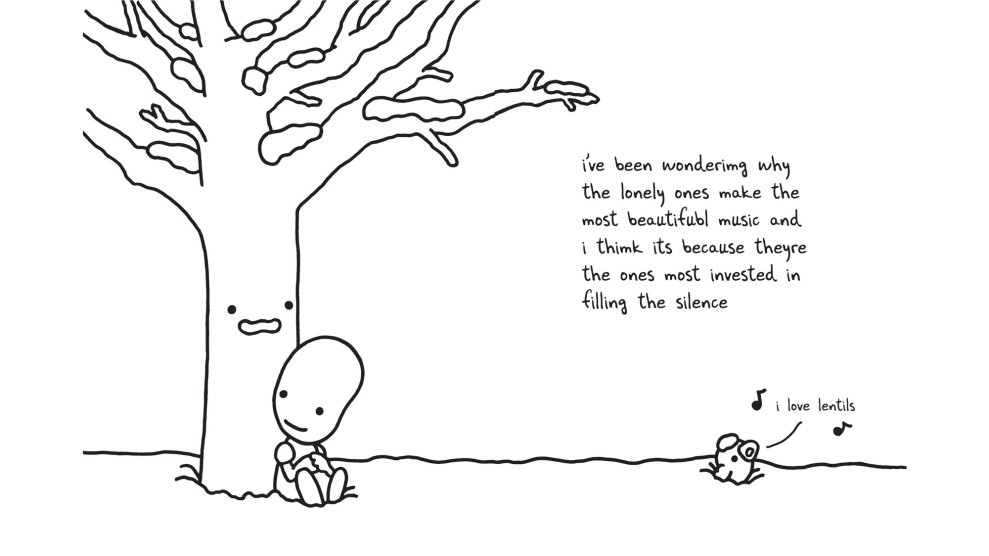

Jonny Sun/Harper Perennial

If you spend time on Twitter, you may have encountered a character named Jomny Sun, an adorably witty and philosophical alien with nearly half a million followers. For the most part, Jomny’s tweets are silly and weird, riddled with playful typos. But over the last year, Jomny has developed a more serious side. He’s waded into politics. Like this:

everyday im more terified that a nuke will be launched & that im gonna find out through someone tweeting a screenshot of a push notification

— jonny sun (@jonnysun) May 9, 2017

Jomny’s creator, a second-year MIT PhD student in urban studies and planning named Jonny Sun, says Jomny’s political awakening was intentional—and he’s hoping that it will serve a purpose. “Humor is this way to get people on board or to get people to listen to stances they wouldn’t typically listen to,” he told me.

Jonny’s been thinking a lot about that idea lately. During the school year, he hosts the MIT Humor Series, discussions around internet humor as a tool for political discourse and social inclusion. He’s also the author of a new book about Jomny, Everyone’s a Aliebn When Ur a Aleibn Too. I talked with Sun about his creative process, humor in the age of Trump, and perpetually searching for a sense of home.

Mother Jones: How did you decide to create this Twitter account?

Jonny Sun: I created the account and started tweeting comedy stuff after I moved away from Toronto. When I did my undergrad in Toronto, I was part of this sketch comedy group, basically this weird family of comedy people and writers, and we would write and perform our work. When I moved away from Toronto to do my master’s in architecture, I didn’t have a place to write comedy anymore. I was on Twitter at the time, and I just started finding more and more strange, surreal, funny accounts. I needed this outlet to write, so I decided maybe this will be a cool place to start writing.

The idea of the alien was tied to two things. The first is the idea of me as a Canadian living in the US, which doesn’t seem like too much of a difference but it was just enough to feel a culture shock in very subtle ways and make me automatically feel like an outsider. The broader part of that is just my identity as an Asian male comedian and a child of immigrants. I think I’ve lived my entire life feeling like a bit of an alien or an outsider, so the decision to make Jomny an alien wasn’t really a conscious one.

[first day at new job]

resist the urge to imediately alienate urself resist the urge to–

[to first persobn i meet]

i actualy hate cofee— jonny sun (@jonnysun) May 30, 2017

MJ: What is it about your humor and your approach to your humor that you think really resonates with other people and allows you to—borrowing the words of your Ph.D.—build a sense of place for them?

JS: I think this sense of being an outsider that’s associated with the account appeals to a lot more people than we like to imagine, and I think that gets to the heart of a lot of the human experience: to feel alone among others. That’s one aspect. Then a related aspect—again I think growing up as who I am, especially as an Asian male in comedy, I’ve been in a lot of situations where my visible race and identity have been the joke or have been asked of me to be the joke. Developing like that has made me very aware of how comedy can be used to exclude or to present biases or to reinforce stereotypes. That has helped me form this mission of making humor inclusive and positive and supportive. And I think that type of humor is really resonating out, especially given the rest of the world.

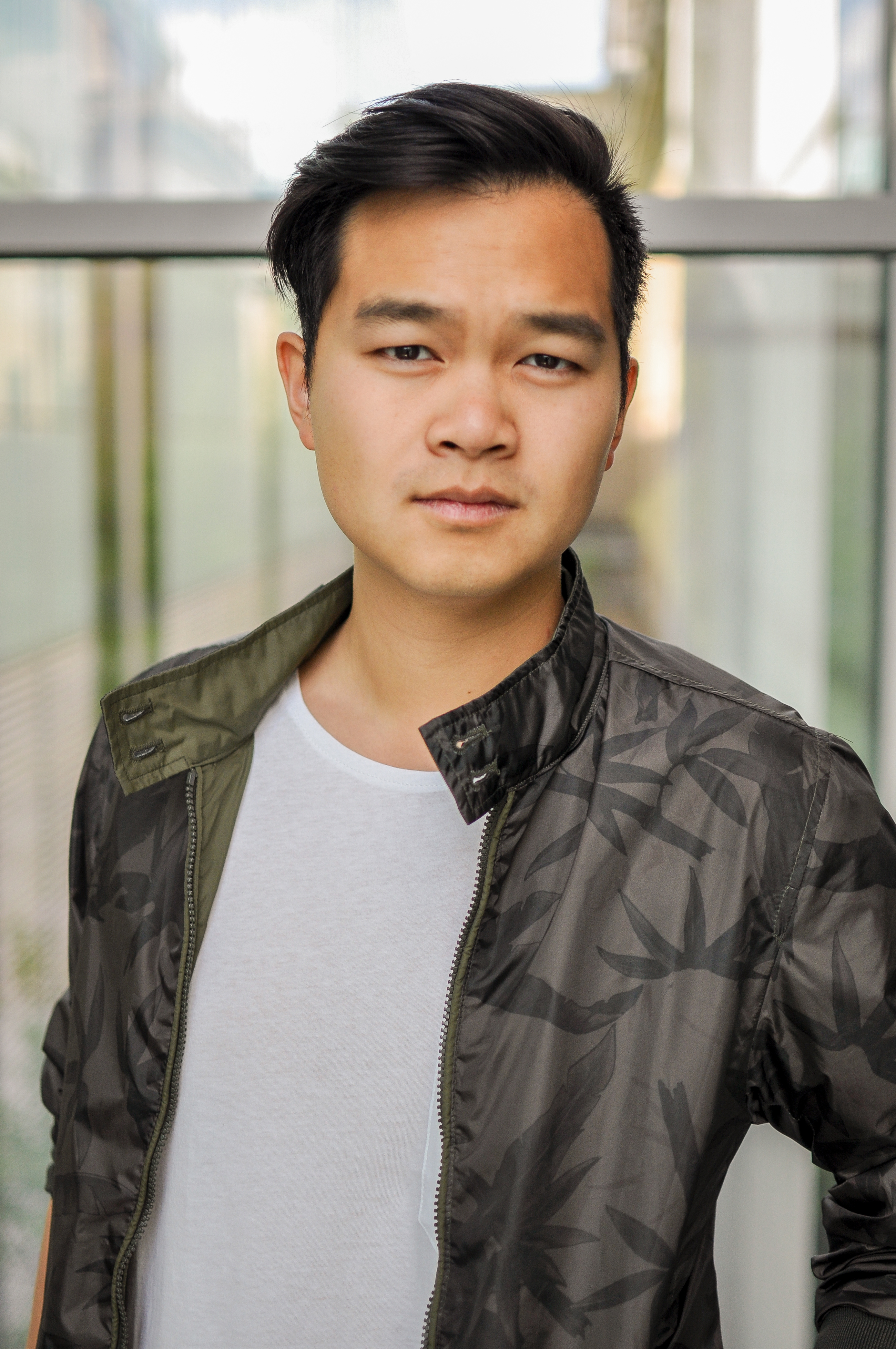

Jonathan Sun

Alexander Tang

MJ: Where do you draw your inspiration from?

JS: I feel like I could list a hundred different sources of inspiration! I love a lot of things, and I think part of the way my brain works is that when I really love something, I try to figure out what about that thing is so amazing to me. So I go about the world falling in love with things and then seeing why I fell in love with those things. All of that eventually folds in and gets internalized and then comes out again. That’s kind of a non-answer (laughter). But I try not to be limited in my own work.

MJ: So, even though you say that this Twitter account is a personal thing for you, now in the age of Trump, do you feel an obligation to use your voice to push the conversation in a more positive direction?

JS: Definitely. I always think about responsibility and what it means to be lucky enough to have some sort of platform where a lot of people will see what I write. I’m very aware that that has some power and influence to shape norms or to shape the way people see things. I’m not expected to be a political voice; I’m expected to be a fun, positive account. In some ways, because of that, I have the ability to reach a broader audience than explicitly political accounts. There’s some responsibility to having that reach, and there’s some power there.

MJ: Do you feel humor has limitations? Are there certain things that should not be joked about?

JS: That’s a very hot topic nowadays. I think you have to be very careful. I don’t think humor is a neutral thing. It has this power and this ability to frame different arguments in different ways. Some jokes can really punch up and help people think about different power structures and point out the ridiculousness of things. But humor is also used a lot to punch down and to victimize people who are already oppressed. So, I think there’s a way to joke about almost anything, but it just depends on who is being joked about.

MJ: Let’s talk a little bit about your book. Tweets are fleeting but books are forever. In the process of creating this book, did the change in the medium also change the way that you approached your humor?

When I tweet, I’m not thinking of it as a long-term project; I’m trying to put stuff out day-to-day that’s honest and true to what I’m feeling or thinking. So when you take all that data and collapse it into common threads, it gets really interesting. A lot of these common threads are about self-worth, what it means to both be sure of yourself but also be sure of the creative process and what you’re making. A lot of it actually had to do with MIT and the pressure of the institution. I don’t think I ever explicitly expressed that in the book, but it’s funny because when Lin-Manuel Miranda’s wife, Vanessa, who also is an MIT graduate, read the galley, she tweeted at me, Oh, it’s very clear that this is about MIT. That definitely wasn’t my intention, but I like the idea that somehow, just through doing this stuff, I’ve been able to accurately portray my life experience in ways that I wasn’t even trying to.

Of course, I lied.

YOU'LL CRY.

But you'll cry happy Antoine de Saint-Exupéry Little Prince tears,

not wracked Stay Alive (Reprise) tears.— Lin-Manuel Miranda (@Lin_Manuel) May 30, 2017

Enjoying @jonnysun's #jomnybook about humbanity, friendship &, evidently, [dam] engineers. I share as homage to our alma mater @MIT. #PiDay pic.twitter.com/yZwdMFmC6V

— Vanessa A M Nadal (@VAMNit) March 14, 2017

MJ: Okay, here’s a really hard question I have for you: What is one of your favorite jokes that you’ve tweeted of all time.

JS: Oh my gosh. That’s such a hard one. The one that I’ve been thinking about lately is one that I actually tweeted a spread of. “I’ve been wondering why the lonely ones make the most beautiful music and I think it’s because they’re most invested in filling the silence.”

MJ: Oh, I love that one, yeah.

JS: It isn’t really a joke, but I kind of think of everything I tweet as within the realm of humor even if the punchline might incite a different emotion other than laughter. It’s a joke in terms of its construction and structure because you have the setup and the reveal. I guess I’m just proud of that idea and the way that I was able to write that.

MJ: So my last question is about the oft-referenced “so come home” one. I’ve always wondered: What were you trying to say in that little joke? And why do you think it resonates so much with people?

"i just want to go home" said the astronaut.

"so come home" said ground control.

‘‘so come home’’ said the voice from the stars.— jonny sun (@jonnysun) October 1, 2014

JS: I think it comes down to this idea that we were talking about earlier, which is that everyone has that feeling that they don’t necessarily belong. I’ve definitely been going through my entire life trying to search for different places to call home. I think I wrote that tweet around the time when I was thinking about if I should be doing a Ph.D. and, again, deciding to move to a new place. What I tried to do and I think what people read and connect with in that tweet is the idea of a constant battle between going back to where you’re from versus venturing forward. For me, I was born in Calgary, Alberta, and I moved to Toronto when I was really young. But my parents still own our childhood home in Calgary. Every time I go back, it’s such a bittersweet feeling because I know this is part of my life, but it doesn’t feel like my home. That feeling of knowing that where you’re from isn’t really the place you would call home is kind of embedded in that tweet.

Then there’s this ambition and this hope that in moving forward, you’ll be able to find a more perfect place. There’s almost like a kind of pursue your dreams, pursue your passions message in there as well because obviously an astronaut would aspire to find a home in the stars. That’s what I’m trying to do too: to find a place where I belong through my work and through the stuff that I’m trying to make. I still haven’t gotten there, but I would say that I’m a little bit closer.