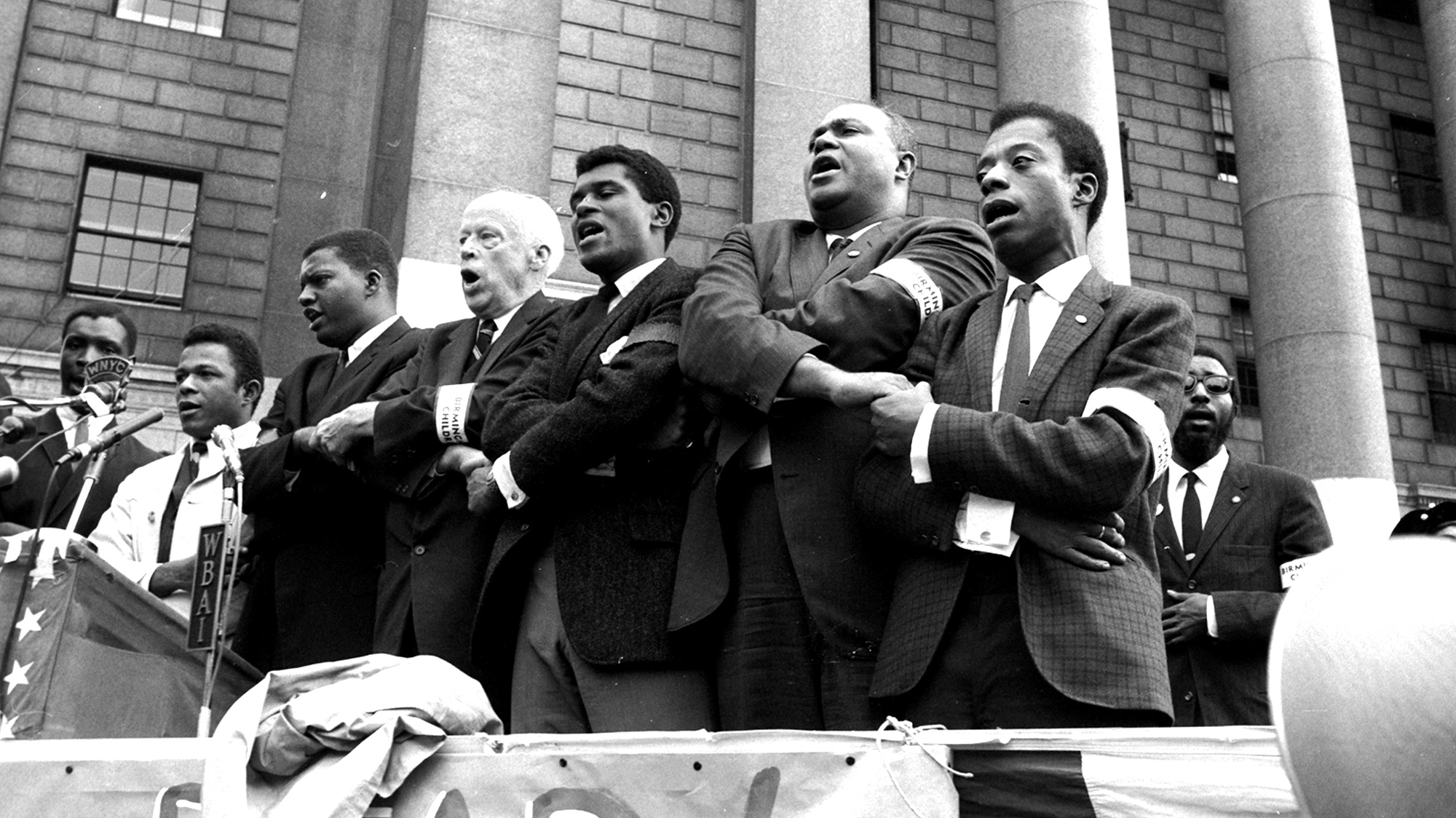

Civil rights activists including James Baldwin (front, far right) sing at a memorial for victims of an Alabama church bombing in September 1963.

Jacob Harris/AP

On Super Bowl Sunday, President Trump sent out a tweet that called on Americans to “proudly stand for the national anthem” during the football game in honor of the service men and women to whom “we owe… the greatest respect.” Couched in a reverence for the military, the tweet was almost certainly intended as a dig at black NFL players who, off and on for almost two seasons, had been kneeling during the National Anthem in protest of police violence and racial injustice against African Americans.

Support and opposition to the protests is largely split along racial lines. In an essay last November, I made the case for why that might be, exploring black Americans’ different relationship to symbols of Americana through the history of a song known to few white Americans, “Lift Every Voice and Sing.”

In her new book, May We Forever Stand, author Imani Perry delves more deeply into the history of “Lift,” which many black Americans think of as our own national anthem, and examines how the song came to be the centerpiece of black formal culture for much of the 20th century. I reached out to Perry to discuss the book, and what this rich history adds to the national conversation about patriotism.

Mother Jones: Why did you want to write this book?

Imani Perry: A couple of reasons. There’s so much wonderful work that’s come out in African American studies over the past decade. But there’s a piece that’s absent: black formalism, black ritual, and institutional culture in the context of Jim Crow. “Lift Every Voice and Sing” was in some ways the signature feature of that. That aspect of black life hasn’t had a full exploration or vetting, with the exception of some work in educational history. Also, there has been some really good work done on the song itself and [its composers], the Johnson brothers, but there hadn’t been work done on the song in black communities and how it operated.

MJ: What was your research process?

IP: I went through black newspapers and magazines. Memoirs. School programs. Curricula of southern schools. The newspapers were all through the course of the 20th century—mainstream newspapers like the Philadelphia Tribune, the Pittsburgh Courier, the Baltimore Afro-American—those kinds of publications. I also looked at the Black Panther Party newspaper and smaller entities. I looked at conferences—the history of [Martin Luther King’s] Southern Christian Leadership Conference, their programs. All kinds of black organizations. The National Association of Colored Women. I went basically through the archives of black institutional life to find where this song was. So [I did] some traveling to different [black college] campuses, but a lot of the stuff was in archives that had been digitized. I bought a lot of books, too. Early African American children’s literature that at times had references to the song. It was really a process that was cobbled together—five years off and on.

MJ: What’s most important for people to know about the historical relationship of black Americans to this song?

IP: Three things: There was meaning to the song in context—not just the song but singing the song together gives you a sense of connection. Second, the song was a form of education, so it sets forth a set of values and principles. So, insofar as a primary part was singing for young people, it was really important in terms of teaching certain messages about black people. Third, it really was, and remains, a way of telling the story of black people in this country in epic terms—a history that is difficult, complicated, but also has moments of glory. That’s the message of the song. And in that period when it was written [1899], that’s a really important gesture. Black Americans were conceived of as people without a history, and then this song says there’s a glorious history and important history to tell.

MJ: How has black people’s relationship to the song today changed from what it was during the song’s heyday?

IP: The main thing is that we don’t have institutional and associational life the way that we used to. Americans aren’t as tightly networked in terms of belonging to various groups. So we sing the song ceremoniously on an annual occasion or Black History Month or a Martin Luther King event. But it’s not woven into the fabric of daily life.

MJ: What would you say is the relevance of this song to the conversation we’re having today about patriotism, and showing respect—or lack thereof—for the standard American symbols?

IP: Patriotism at its worst is a demand for a simplistic fidelity [to a nation] regardless of the content or context—you have to just go along. We associate that with some of the worst political regimes in history—with authoritarianism. Patriotism at its best is about investing some sense of value in the nation, but also a commitment to making it live out its creed and principles of equality or liberty or justice. “The Star Spangled Banner” has such disturbing messages in it. “Lift Every Voice and Sing” is a remarkable piece, because it is patriotic but it’s a patriotism that actually doesn’t have to be attached to a specific country. It doesn’t mention the United States. It’s a patriotism that’s about what it means to be dedicated to a nation and honoring ancestors and principles. Insofar as there can be a good patriotism, what “Lift Every Voice and Sing” offers is the best possible version of that.