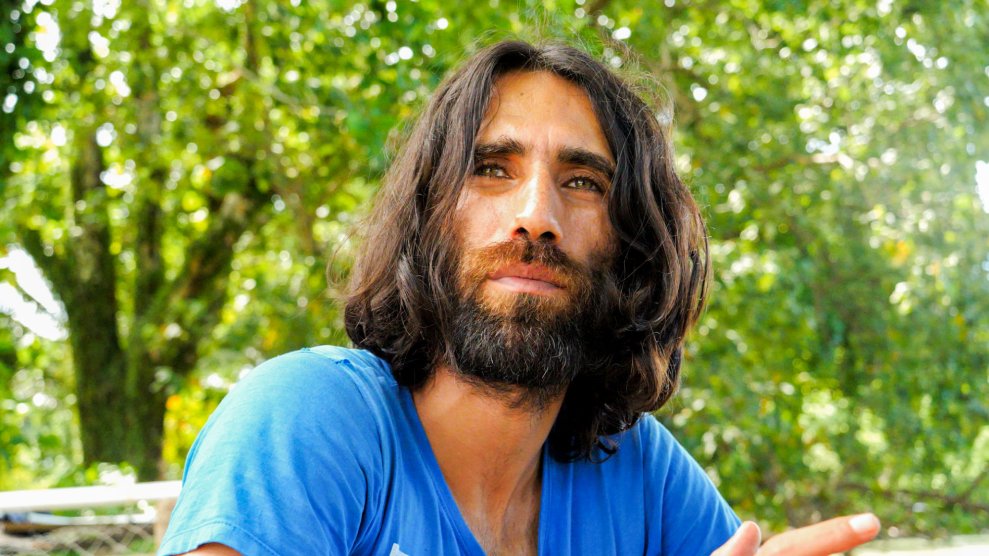

Behrouz BoochaniCourtesy of Amnesty International

Kurdish Iranian writer Behrouz Boochani has spent nearly six years locked in a detention center on Manus Island in Papua New Guinea, barred from entering Australia under the nation’s hardline immigration policies.

But prison didn’t stop Boochani from writing a book, composed one WhatsApp text at a time to his translator. Now Boochani’s autobiographical book, No Friend But the Mountains, has been awarded the 2019 Victorian Prize for Literature, which comes with a $100,000 reward. (His book also won the $25,000 prize for nonfiction.) Judges described the book, an account of his long struggle for freedom, as “a stunning work of art and critical theory which evades simple description.”

Australia has kept asylum-seekers and migrants, often for years, at offshore processing centers, akin to how the United States treated Haitian refugees at Guantanamo in the 1990s. Boochani, who fled persecution in Iran and was captured at sea en route to Australia, said he had “a paradoxical feeling” when learning his book had won.

“My main aim has always been for the people in Australia and around the world to understand deeply how this system has tortured innocent people on Manus and Nauru in a systematic way for almost six years,” Boochani told the Guardian by text message. “I hope this award will bring more attention to our situation, and create change, and end this barbaric policy.”

In his acceptance speech, delivered by video from prison, Boochani said that maintaining an image of himself as a writer helped him uphold his dignity, even as he endured difficult and humiliating moments in prison.

“I have been in a cage for years but throughout this time my mind has always been producing words, and these words have taken me across borders, taken me overseas and to unknown places,” he said. “I truly believe words are more powerful than the fences of this place, this prison.”

Recharge is a weekly newsletter full of stories that will energize your inner hellraiser. Sign up at the bottom of the story.

-

“I just want to inspire them.” Ana Chavarin had to drop out of school at age 13 to work in a factory in Mexico to help her family. At 37, after years spent undocumented in the United States, Chavarin bucked the odds: She obtained legal status, returned to school, and got an associate’s degree.”To me, it was an addiction,” Chavarin said about her first days in class. “I wanted to be there in class every day. I wanted to learn more.” Chavarin, a house cleaner and community organizer who wants to be a therapist for sex-assault survivors, said she hopes to set an example for her four children. Her oldest, Jorge Lopez, who is studying to become a nurse, says his mom has inspired him: “Her being so motivated to first get her GED and then be the first one to go to college definitely gave me that motivation to [be] like, ‘I got to do it as well.'”

Chavarin intends to keep studying and get a Ph.D. (PRI’s The World)

- She had to act. As temperatures plunged to negative 20 degrees last week in Chicago, Candice Payne, a 34-year-old real estate broker, made a spur-of-the-moment decision to help the city’s homeless. She put 30 hotel rooms on her credit card and housed 100 homeless people from the worst of the cold. Additional donations doubled the number of rooms available, allowing them to extend their stay through Sunday. Restaurants pitched in food, and Payne handed out care packages of toiletries, snacks, and prenatal vitamins.

“I am a regular person,” Payne said. “It all sounded like a rich person did this, but I’m just a little black girl from the South Side.” Having taken the lead, she was struck by how many strangers joined to help. “After seeing this [response] and seeing people from all around the world, that just tells me that it’s not that unattainable. We can all do this together.” Thanks to reader Neil Parekh for this story suggestion. (New York Times)

- A fitting tribute. Captain Rosemary Mariner became one of the first six women to earn her Navy wings, the first woman to fly a tactical fighter jet, and the first to command a squadron. At her funeral on Saturday, the Navy honored her with another first: a flyover of fighter jets piloted exclusively by women. Though she is honored now, Mariner faced resistance throughout her trailblazing career, says longtime friend Martha Raddatz, an ABC correspondent. “She would say the problem first was that men were afraid [women] couldn’t do the job. And then they were afraid that they could.” (Washington Post)

- Hands across the water. Back in November, we highlighted the story of a Dutch church protecting an Armenian family from deportation by holding continuous religious services. After hearing about the church, Joel Miller, a minister from Ohio, traveled to the Netherlands to help, joining 800 other clergy members who have also delivered services. Miller had something in common with the church: His congregants at the Columbus Mennonite Church had also offered sanctuary to an immigrant facing deportation.Miller praised the power of churches working together: “As Martin Luther King [Jr.] says, we’re ‘small in number but big in commitment.'” (PRI’s The World)

- A marathon save. Khemjira Klongsanun ran 19 miles of a marathon carrying a lost puppy she saw on the road, finishing the race with the pup in her arms. When no one claimed the puppy after the race in Thailand, she adopted him. Carrying the pup made the marathon twice as tiring, she said, “but I did it anyway, just because he is adorable.” Thanks to Erin Ruberry for this story suggestion. (Runner’s World)

Have a Recharge story of your own or an idea to make this column better? Fill out the form below or send me a note at recharge@motherjones.com.