Jasu Hu

Can the very online ever unplug? An entire cottage industry has sprung up around this particular anxiety: everything from offline vacations and “digital detox” apps to books about how we might uncouple ourselves from an economic order in which our very attention is a commodity.

Mother Jones put the question to four writers with varying degrees of internet damage. From healthiest to least healthy: Oakland, California, artist Jenny Odell, author of How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy; New Yorker writer Jia Tolentino, author of Trick Mirror: Reflections on Self-Delusion (whose press materials describe her as “what Susan Sontag would have been like if she had brain damage from the internet”); Mike Isaac, a New York Times reporter and author of Super Pumped: The Battle for Uber; and Ashley Feinberg, a very funny reporter for Slate, who has tweeted twice in the time it’s taken you to read this clause.

The four of them recently joined Mother Jones in an online chat—condensed and rearranged here, with minor edits for clarity—in which we discussed reclaiming and retraining our attention in an economy built on capturing and manipulating it. We talked over Slack, which was a bit like holding a mindfulness seminar on the infield of the Indy 500.

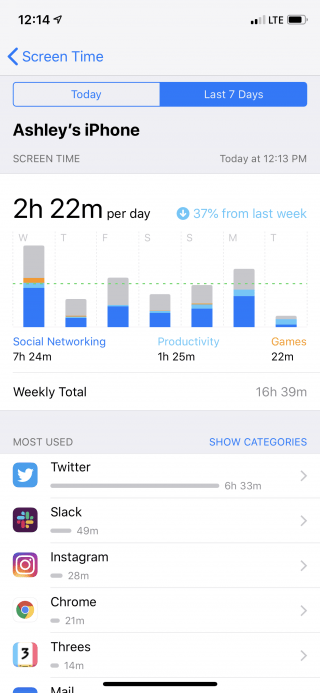

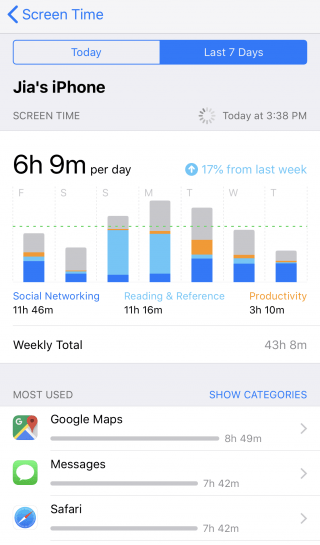

Maybe this is too invasive for a first question, but I’d like to know what everyone’s iPhone screen-time stats look like. Here are mine:

Jenny Odell: My phone is senile. It’s so old that it stopped updating. I remain blissfully unaware of my screen time.

Ashley Feinberg: Before I upload this I just want to preface that I’m recently unemployed.

Mike Isaac: Mine is better than I thought. There was a point for me, during my book leave, where i averaged 8 hours. That gave me my own personal crisis.

MI: Also pardon the name of my phone.

AF: Christ, Mike.

Jesus. Does your phone have truck nutz on it?

Jia Tolentino: My screen time over the past week is incredibly embarrassing because I was in Utah for four days hiking and driving remote roads so I was using my phone constantly to navigate and figure out things, and then was killing hours and hours at the airport by looking at my phone instead of a book.

Before I read Jenny’s book my screen time was about 4 hours 30 every day, sometimes 5. After I read Jenny’s book it went down because I had a life-changing, positive crisis.

What was the crisis?

JT: The crisis was: Has capitalism distorted me at the level of desire? The answer was: yes.

Anyway it’s 6 hours average over the past week.

For all four of you, I’m wondering how you think your attention span has changed over the past decade or so

AF: I’ve lost the ability to retain new memories. I’m almost positive this was not always the case. I’ve never had a good memory, but I used to remember, say, what I did the day before mostly.

JT: I mean, I work from home and am alone all day, so I don’t want to discount the ability to group text and whatnot to keep me sane. My attention span is my most prized possession, and it is a piece of shit compared to what it was five years ago, and 10.

The quality of my attention changed drastically when I started working at The Hairpin in 2012, then again when I started working at Jezebel, and then again (for the better) when I started working at The New Yorker and got off Slack and stopped needing to use Twitter to find stories to “assign.”

Do you think it’s the quality of attention, or is it the distribution?

JT: It was the quality of my attention and the distribution both—the things I was attentive to, the cadence of my attention, etc. Like, you guys know the feeling when you end up looking at Twitter too much too early in the day, and then for the rest of the day you’re just totally fucked? Like your brain is like a grasshopper, and it can’t sit still at all?

JO: Yes!!!

MI: Yep.

AF: Honestly no. That’s my constant state.

JO: I don’t think my attention span has necessarily changed, just that I’m more aware of which things can hold my attention in a way that doesn’t make me feel insane.

MI: I’ve had to actively work to come back from the headspace where I can only pay attention to 140-to-280-character-count missives. Honestly it was a concerted effort to read actual books.

JO: Reading actual books is great.

AF: I’ve found that I can still read books normally, but I cannot concentrate even remotely on a Kindle. The screen just triggers something in me where I have to look at everything around me.

JT: Yeah, I read paper books for one to two hours before bed and that’s the saving grace of my broken brain.

JO: Agreed, there’s something about reading on a device that’s also trying to be 1,000 other things. A book is just a book.

JT: Sometime around when we were all on the Gawker slack begging for the meteor to hit us, I realized my brain had been permanently degraded by the internet, and possibly also my sense of desire, solidarity, ethics, morality. And yet it was fun to beg for the meteor to hit. I have a whole section about that in my book.

MI: I need to plug my book.

Uhhhh, Uber wrecked my brain. Buy my book.

JT: lol. My brain is broken…pls read.

But so I think that the internet, by being organized in the form of social networks that are centralized on personal identity, has blurred multiple separate ideas of solidarity, to where political solidarity and civic solidarity are permanently enmeshed with the solidarity that comes with lived experience.

You can’t express solidarity with someone without somehow inserting yourself into it—partly because that’s just how these platforms are structured.

And then you get this:

There are types of solidarity that can and should be expressed without centering the self. And the internet forces the self to be centered in every interaction.

I watched a TikTok meme today that made me laugh for 15 minutes, and i was realizing that the thing that always brought me pleasure about the internet was surprise, and the thing that brings the least pleasure about the internet is the lack of surprise. Memes feel surprising so they’re good.

This is the TikTok. You have to have sound:

Everything else feels predictable and bad.

AF: The thing that brings me the most joy is just, like, finding embarrassing shit about people. It doesn’t have to be famous people, even just friends. It’s like a puzzle trying to follow old-screen-name clues and shit to see what embarrassing internet garbage they’ve done in the past. And it’s extremely rewarding.

What feels the worst is definitely when some Republican ghoul manages to get an outrage campaign going over something I tweeted. It’s all people I disagree with and think are idiots, etc., etc., but just seeing the constant stream of vitriol will always feel extremely bad.

JT: Yeah, Ashley, it’s been wild to leave the umbrella of Gawker and no longer have people trolling me nonstop. I actually find it offensive (WHY STOP NOW, YOU COWARDS), but it’s a huge relief. I could feel my skin thickening so much at Jez in a way that scared me a bit.

MI: You pinpointed the exact thing that bothers me the most earlier in this conversation. Waking up, reaching for my phone, turning on Twitter and getting instantly hammered with shit. Also, I live on the West Coast, so every day is like walking into Mad Max, and I spend at least an hour divining who is fighting who about what, and what some subtweets even mean.

One or two of the private Slacks I am in bring me great joy. I think retreating to groups and private Slacks in particular is going to continue happening. (Which is why Facebook positioned itself as private and is working “Groups” into its main blue app. And why Twitter will someday be in trouble.)

JT: I have been avoiding private Slacks, though I suspect they would bring me a lot of the joy that I seek out instead by constantly texting. Not having to be on Slack for work feels like an incredible opportunity to just not use Slack.

MI: It’s probably worth mentioning that at least some of us work remote or alone a lot of the time, so part of this stuff is probably helpful in some “staying connected” way.

I think the key is to turn off all notifications.

JT: Slack is so addictive in its userface.

USERFACE

USER FACE

FUCK ME

I’m 59 years old.

Jenny, you write a lot about persuasive design in your book. That’s the practice of influencing human behavior through screen elements like notifications. What sort of persuasive design elements in Slack jump out at you right now?

JO: Well, apparently Slack needs my permission to enable desktop notifications. I tried to say no and it now says we strongly recommend enabling desktop notifications.

AF: Now I’m wondering if I should turn off notifications. I’ve trained myself to ignore them, mostly, so now they exist in the corner of my eye as an anxiety-inducing blob.

MI: Kill all notifications except the essentials.

JT: Wasn’t Slack designed as a side communications app while they were trying to build a video game that had no goal or end? Which is so metaphorically indicative?

JO: A video game that had no goal or end ??? i.e. the internet?

AF: I just turned off all my Slack notifications. Thank you.

JT: I listened to the radio all weekend because I was in Utah with no service, and it made me think a lot about something Jenny wrote about how algorithms “entomb” us in stable images of what we already like. And that, I think, is what scares me most about the internet—the idea that things about me will only ever be intensified and monetized, rarely de-escalated or shifted in a way separate from monetization.

I’ve just been thinking a lot more about surprise, and it’s interesting to see where something like TikTok fits in. I think we’re drawn to it because it has a lot of capacity to surprise still.

JO: Have you ever tried the “IMG XXXX” search? I learned about it from Joe Veix (my bf)—it’s where you go on YouTube and type in “IMG” and a random four-digit number.

AF: Oh I LOVE that shit.

JO: You get these videos with, like, two views. Here is a compilation of some of my favorites:

AF: Oh I forgot I wrote about this a long time ago. I used to love that stuff but feel like I’ve gotten away from it as Twitter has consumed everything I do.

JT: Yeah, you can feel the algorithm tightening

Ashley, you’ve talked a lot about actually liking the frenetic pace of the internet.

AF: Yeah, I am naturally very impatient and have always liked hectic things. None of that feels weird. The problem is mostly that being that way is not good for functioning normally in the world, and the internet lets me indulge in it entirely.

So where I’d normally have to force myself to focus in an internet-less world, there is an option now to just…not do that

JO: Ashley, if it makes you feel any better, this is from William James’ book on psychology from 1890:

The natural tendency of attention when left to itself is to wander to ever new things; and so soon as the interest of its object is over, so soon as nothing new is to be noticed there, it passes, in spite of our will, to something else. If we wish to keep it upon one and the same object, we must seek constantly to find out something new about the latter, especially if other powerful impressions are attracting us away.

(It made me feel better anyway.)

AF: It does a little! The thing with me is, I don’t really actively worry about any of this. It’s annoying that I can’t make new memories, for instance, but I sort of feel like, this is what I’m working with now.

JT: That is fascinating, Ashley. Are you in general not an active worrier?

AF: Not at all. I wish I had more anxiety tbh.

JT: That’s why you’re so good at the internet. It’s like you have the behavioral patterns of anxiety without the actual thing. I sort of am like that, is why I’m saying that—not trying to project on you.

AF: lol no I think that’s right!

To me it’s more like, if someone cut my arm off, I just wouldn’t have an arm anymore—time to figure out how to not have an arm and move along.

JT: Ashley omg. “Time to just not have an arm, bitch.” You inspire me.

JO: Striding armless into the dark night of the internet.

JO: It has to do with recognizing the value of (and caring for) what’s already here, rather than trying to replace it or pursue “innovation” for the sake of innovation. It’s basically the opposite of “disrupt.”

You write about it as if it were a physical ordeal, to be “trained” for, with “exercises in attention.” What sort of exercises do you mean?

JO: A lot of the examples I give for retraining attention come from art. There’s been a lot of talk about persuasive design, whether designers should be making “more ethical” persuasive design, i.e. persuading people to spend their time “better” (read: more productively). It just makes me suspicious. I would like to recenter the training of attention in the individual.

JT: I’ve implicitly been trying to retrain my attention for a few years now: putting social media blockers on my phone, making sure I read a paper book at night, no notifications, etc. But it has been helpful over the last year to really bathe in the desperation of why and to replace it with an idea of what you could actively pay attention to instead—an idea of what it feels like to sustain those shifts rather than just to efficiently slot them in.

You both seem to conceive of attention-economy self-care in the Audre Lorde sense of self-care—politically engaged, an assertion of the value of the self, that sort of thing.

JO: Yeah, self-care that actually contains reflection and the capacity for surprise, versus the sort of “digital detox in order to perform better.”

JT: I’d been thinking of the attention training as a sort of a common-sense tool to function, which was OK but not the shift I needed, because all of my life is already set up around efficient production. And now I am trying to do more good nothing. 🙂 I always think about the fact that everything really, really amazing in life is both inefficient and essentially beyond the reach of technology. Love is inefficient, true friendship can be inefficient, true experience can’t be captured—I think about trying to safeguard those things.

JO: Yeah, I once met a very Quantified Self guy who had a spreadsheet of his entire life. It was so detailed, and there was a score at the end of every day. The low scores were in red.

JT: * weighs a turd on a scale *

JO: I want to ask these people why, and then why again.

JT: But as someone who is already temperamentally geared toward liking the pace and speed and dizziness of the internet—which is why i started working at The Hairpin while I was in the haze of grad school for fiction—I feel worried about the internet’s capacity to narrow me to just those qualities at the expense of the really good stuff, and narrow the way I live in the world to those qualities, too.

But at the same time I have completely relied on all the bad things about the internet to even create a career. So as with everything these days I feel pre-implicated and fucked 🙂

MI: I think about that last part a lot. This shithole made me.

I want to know about this process of doing more “good nothing.”

JT: It was, as Jenny puts it, an ethic of living that actively valued maintenance and caregiving over production, which is something that I have always I think tried to do. Every year my secret New Year’s resolution is to be a better friend and community member, but the incentives to value production over everything were doubled by certain things over my past year. So I started thinking that if I didn’t [retrain my attention] I would have a scorched-earth landfill in my brain instead of a backyard. And I bought a bunch of plants and considered in what ways I could behave in a way that was more inefficient and conscientious (and fun).

JO: I just had someone email me about how she adopted a kitten while she was reading my book (!) and she had similar feelings.

JT: Having a dog has always helped me with doing good nothing. Plants have helped—I have so many; I went from 0 to 17. Trying to reorient my life toward purposeless spontaneous experience has helped.

JO: Jia, do you ever feel pleasantly creeped out by the fact that something is growing in your apartment.

JT: Yes! I wish I could look at my plants move. Basically I’ve been trying to think more like I’m on acid all the time, and it’s helped…🙂 Like when you’re on acid you simply cannot look at your phone, too. You are dazzled by the miracle of being alive. How I’m tryna be.

AF: Oh man with notifications turned off, I completely forgot we were doing this.

Artist Jenny Odell is the author of How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy. New Yorker writer Jia Tolentino is the author of Trick Mirror: Reflections on Self-Delusion. Mike Isaac is a New York Times reporter and author of Super Pumped: The Battle for Uber. Ashley Feinberg writes for Slate.