Mother Jones Illustration

On a cold night in January 2011, 300 people piled into Hugh Ryan’s loft in Bushwick, Brooklyn. It was a special evening for Ryan. His Pop-Up Museum of Queer History was making its debut, right here in his living space. Together with more than 30 exhibit makers, he had curated a makeshift museum that offered a comprehensive exhibit of queer history. “Somewhere between an art experience and a party, it was going to just be a single event to see what it would be like if there was such a thing as a queer museum, run by queer people, in queer space, with queer exhibits, by queer exhibit makers,” says Ryan. “It was fantastic.”

Yet, as history has shown, where queer people congregate, police tend to follow. Among those 300-plus people who filled every corner of his loft? Undercover cops—14 of them, in Ryan’s telling. When the clock struck midnight, the event got shut down, thus ending the exhibit’s life. Briefly. “My plan beyond this was to clean up and have breakfast,” remembers Ryan. “But people were so hungry for it.”

Ryan, along with other local curators and queer community leaders, took the pop-up concept around the country, from Philadelphia to Indianapolis. Each new local event, Ryan recalls, was met with “an incredible response,” but when they brought the pop-up museum back to Brooklyn, “people kind of scratched their heads and were like, ‘Queer history’?”

That’s when Ryan realized: “Wait, I don’t know anything about the queer history of Brooklyn, either.”

The New York native didn’t set out to write the book on Brooklyn’s queer history, but that’s exactly what happened. “I was like, shit, I gotta do this research, I’m really just interested,” he says. Ryan is no stranger to research: The author and historian regularly contributes to the Condé Nast publication them, has explored the literary origins of zombies, and has written about Rube Goldberg machines for the New York Times. “For years I was just doing research. Maybe it was going to be an exhibit with the Pop-Up Museum, maybe it’d be something else, maybe a series of articles.” He became so enamored with this hidden history of Brooklyn’s queers, he applied for a research grant from the New York Public Library—and got it.

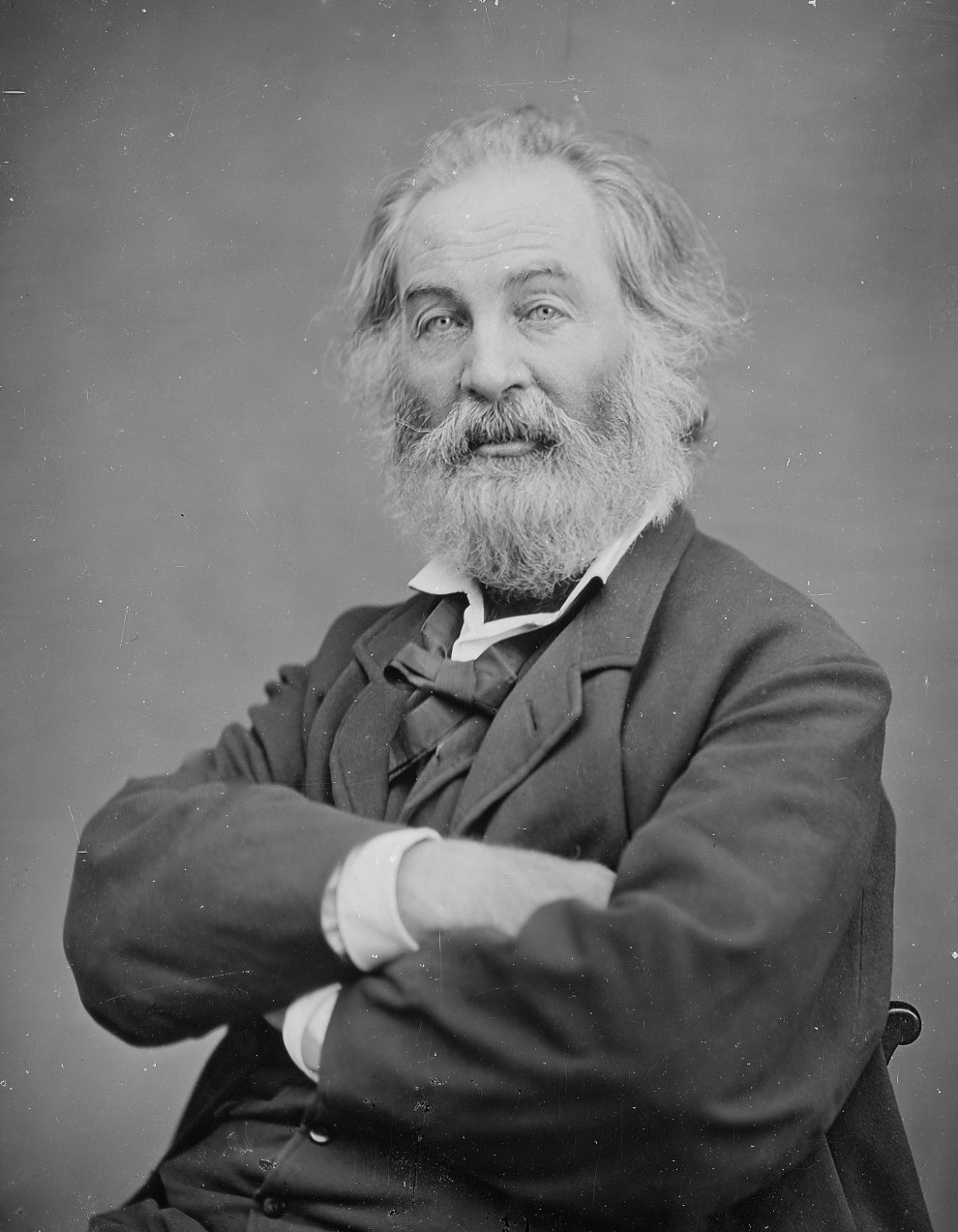

“One of the first things they said to me was, when this grant period is over, you should have your book proposal completed,” he says. “I was like, Oh, I’m writing a book.” That book turned out to be When Brooklyn Was Queer. It opens in 1855 with Walt Whitman, maybe one of Brooklyn’s most famous queers, and from there Ryan takes the reader through a century of queerness, from Whitman’s Leaves of Grass to what Ryan calls “The Great Erasure” in the mid-1900s. It’s over 100 years threaded together, telling a story of a people so often lost to the straight-washing of history books.

Hugh Ryan joined me in Mother Jones’ New York City bureau, where he expanded on Brooklyn’s queer history, dove into the concept of sexuality and gender, and gave me insight into what history could teach about the next conflict in the queer movement. The transcript below has been edited for length and clarity. We’ve also included audio clips with his full responses.

You specifically focus on Brooklyn’s queer history. How did this history mirror the queer history of America at large?

Stewards, Brooklyn Navy Yard ca. 1900.

Universal History Archive/Getty

One of the things that became obvious was the real density of queer history appears when Brooklyn becomes a city—when it urbanizes. When it gets that mix of density, economic opportunity, anonymity, and privacy that introduces people who live around the world and their different sexual mores. That’s a process deeply implicated in urbanism, which obviously throughout the US is a big change that comes—this huge movement of people moving away from rural spaces into cities. Those two themes, urbanism and the importance of intermingling spaces that provide intermingling, apply to the entire country, and the world.

Listen to the extended answer here:

As someone who’s involved in the Brooklyn queer scene today, how do you think that today’s scene has been built upon this history?

That’s a complicated question, because my book goes up to about Stonewall. I stopped there because that’s when Brooklyn’s waterfront economy really tanked. The engine that drives all of this change and this possibility in Brooklyn, is the waterfront. And by the ’60s, the Navy Yard is closed. So the arc I was following sort of ends there. But of course, queer life in Brooklyn doesn’t end there. I’m following one set of stories, and what emerges after that moment is a cacophony of stories.

If I had read something like this in high school, it would have been incredible to have that knowledge about a people you belong to.

In originally coming to queer history I was looking for a mirror. I wanted to see myself somewhere, because I hadn’t growing up. Then, the more I looked at it, the more I was like, Those people are similar to me, but I’m looking through a window, they’re very different. What I learned growing up about homosexuality is it’s always been terrible, and always will be terrible, and it would never change. And the closet is just more and more closety as you go further back. That’s not the case at all.

I was surprised at how welcoming of queer people the country was at certain times. How do you think being queer in today’s climate compares with the moments that you write about?

Every moment is so different. There are ways in which we are much more visible, accepted, open. There’s so much more possibility for us today. When I go back further and look at the Victorian era, we don’t think we see homosexuality very often there—and I would say, as we think of it today, we don’t. These people were living lives where it was expected for them to have incredibly intense homosocial relationships between men, between women. We only understand what we think of today as homosexuality against the backdrop of the death of Victorian homosociality. What becomes obvious after that moment is people who spend too much time with each other, whose friendships between their own sex are too intense, but in 1820, that wasn’t visible because those intense friendships were proper. So I don’t think you can even have a sense of sexuality, as we think of it today, as existing then.

Walt Whitman

Matthew Brady/Buyenlarge/Getty

You begin the book with Walt Whitman, and in doing so you introduced the reader into a past in which the word “homosexual” didn’t even exist. Why is he an example of living in this world devoid of modern queer language?

Leaves of Grass, which he writes and publishes in Brooklyn Heights, is an incredibly queer document in many ways. He consciously conceives of it that way. He writes these poems into it that are about finding “them that love as I myself am capable of loving,” which is how he puts it at one point. He’s trying to write into existence, words, and rituals for something that he was seeing. The idea of saying sexuality was a thing separate from gender was unbelievable. Whitman not only shows us something that looks very similar to what we know today, but he also problematizes it and makes you say, “Oh, this is historically bounded, this started at a certain time.”

Gay marriage ceremony, ca. 1912.

Kirn Vintage Stock/Corbis/Getty

What moments did you see that brought us from a world without this queer language into what we’re familiar with now?

The late 19th century, beginning of the 20th century, we have a model of what’s called inversion. An invert was someone who collapses our ideas of being gay, being transgender, and being intersex. So you were queer, because your body was different—it was all in your body, not part of your brain. By the early 1910s, these doctors and scientists—and queer people—were starting to really look closely at that model and say to themselves, “What if you have a person who is gender normative, but still wants to have sex with someone of the same sex?” One of the moments that for me was eye-opening was looking at the first law in New York City that criminalizes homosexual behavior. It takes the disorderly conduct law that already exists, which is kind of used broadly to arrest people for a lot of different things, and it breaks it down into 10 subsections—pickpocketing, jostling—and subsection eight is about homosexuality. The passage of this law will allow them to track this class of inveterate degenerates who are screwed up in their brains and will never be able to live workable lives—they might have to be in detention forever. They’re incurable—and they’re talking about pickpockets. This tells us something about the swamp from which our ideas of homosexuality and being born that way come out of. That’s what they thought of pickpockets! That’s also what they thought about gay people.

That’s something you did really well in the book, which was illustrate how this evolution of the acceptance of queer people—or lack of—mirrors the public attitudes of America. As a historian who’s spent years researching and writing this book, you’ve been able to look at the ebb and flow of the struggles of the queer community. What do you think the next big conflict facing the queer community is?

Oh, gosh, no small questions. There is an unresolved conflict that lives below the surface of my book, which is that we did have this idea that all queer people are trans in the 19th century—that we have this idea that sexuality and gender are implicated and inseparable. I think that we have never really understood that tension between gender and sexuality very well. Sexual orientation is a very limited concept. It’s very useful—talking about political party, right? You tell me, you’re a Democrat, I know a certain set of things about you, but I can’t really know everything. It’s more of an indicator of certain things, and I think sexual orientation is very much that way. We’re trying to undo that Victorianism that said, no, you can create this very specific box and that will precisely describe human experience. That’s a conflict that still remains with us.