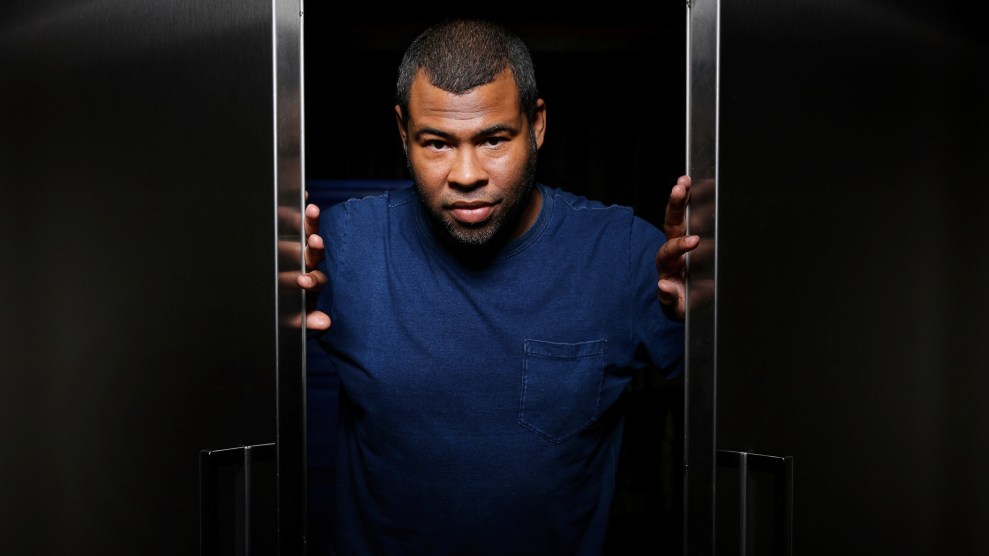

Armando Gallo/Zuma

The staff of Mother Jones is rounding up the decade’s heroes and monsters. Find them all here.

Jordan Peele, that soft-spoken mastermind, has perhaps made the ultimate career moves of the decade from comedic shapeshifter to our modern-day, consciousness-raising Alfred Hitchcock. Before he rattled audiences with Get Out, about the insidious racism of white liberals—that age-old, terrifying tale for Black and Brown people—Peele pushed social boundaries with Keegan Michael-Key in their phenomenal sketch show Key and Peele.

As a sketch comedian, Peele’s real personality was somewhat hidden behind his renowned impressions of President Barack Obama and Meegan, the glam clubgoing extra girlfriend who can only be described as extra. (My favorite is his impression of the Dominican baseball player addicted to slapping ass.) Key and Peele used their characters to inhabit personas of all kinds to make the mundane, ordinary, every day funny. What made those sketches by the biracial comedy duo powerful, though, was the way they balanced a deep understanding of racial relations with absurdity and managed to garner a wide appeal.

Perhaps Peele’s pivot to horror should have been anticipated. In an iconic sketch, “Auction Block,” Key and Peele act as slaves who are frustrated when they don’t get chosen by possible masters. It infuses the terror of the slave trade, the gravest American sin, with painful hilarity.

So it was noteworthy that when audiences embraced Get Out as a work of his quiet genius and his willingness to go there. In Peele’s world, as in our own, racism is alive and well in the “sunken place” of white control of the Black body and mind. The film steeped audiences in the discomfort Black people feel in white spaces. Peele’s films create fear in the subtle and not-so-subtle exploitation of Black characteristics for the enjoyment of white viewers. Get Out is clear-eyed, a bit absurd, and all too realistic, just like those Key and Peele sketches.

Peele infuses his art with odes to the films that guided him, but he’s also known to cleverly sidestep the cliché. Rather than let his protagonist be gunned down, as what happened in a film that influenced Peele, Night of the Living Dead, Chris walked away relatively unscathed, upending the notion that the Black guy is always the first one to die in horror films. (The alternate ending, which came included in the DVD release, showed Chris in prison, serving time for the very violence he was a victim of.)

In Us, Peele briefly set aside a social message for a deeper human one, the most horrifying of them all: We are our own worst enemy. Still, who was experiencing horror onscreen was crucial to Peele’s intent in Us. The movie would have felt cliche with a white family at the center of the unfolding apocalypse.

Peele’s influence is only increasing: He co-created The Last O.G., a comedy about an ex-con (Tracy Morgan) adjusting to life after incarceration. Peele’s Monkeypaw productions helped produce Spike Lee’s most recent masterpiece, The Black KKKlansman. He rebooted The Twilight Zone and revived the story of Lorena Bobbitt in an Amazon documentary.

But perhaps the clearest extension of Peele’s reach will be the “spiritual revival” of the classic horror film, Candyman, which is expected to come out in June. The film, directed by up-and-coming filmmaker Nia DaCosta, is set in now-gentrified Chicago, where Cabrini Green housing project once stood. It leaves us with the unsettling reminder the next horror we must face are the communities we’ve left behind.