“The one class is born to obey, the other to command.” —Seneca

Stoicism begins with a wayward merchant. Legend has it that in 312 B.C. a dye salesman named Zeno was shipwrecked in the Aegean Sea. He washed ashore in Athens, read a book of Socratic dialogues, and found philosophical purpose. His brush with misfortune guided him to the idea of self-control in an uncontrollable world. “Man conquers the world by conquering himself,” Zeno is said to have said. He developed a following.

Soon he and his acolytes were convening in the Athenian marketplace on a porch that would become their namesake, the Stoa Poikile, where they were surrounded by others who wished to draw a crowd—fire eaters, sword swallowers, and the like. Zeno’s doctrines of personal mastery would trickle down to Seneca, a sort of philosopher laureate of the Roman imperial period, and Marcus Aurelius, the Roman emperor—and eventually, two millennia later, to an opportunistic writer named Ryan Holiday, himself a kind of wayward merchant.

“At the core of it,” Holiday, a former marketer for American Apparel, is telling me, “I think there’s something in Stoicism that connects to the philosopher mindset”—he catches himself—“or, sorry, the entrepreneurial mindset.” Zeno is “an entrepreneur,” Holiday explains, “a person trying to make their way in the real world.” Then he begins to rattle off the new mantras of the philosopher-entrepreneur: “You’re responsible for yourself. No one’s coming to rescue you. Make the most of this. Don’t get caught sleeping. Put in the work.”

James Kostecka speaks during StoiconX at the Union City Library in Union City, California.

James Tensuan

Holiday is, most recently, the author of Stillness Is the Key—not to be confused with The Obstacle Is the Way or Ego Is the Enemy, his two other this-is-the-that Stoicism titles. His book sales number in the millions; last January, Holiday’s 2016 book of meditations on Stoicism sold nearly 33,000 copies, he tells me. He also runs a popular website called Daily Stoic (plus a video channel), and he claims his daily email of Stoic advice reaches hundreds of thousands of people, including senators, billionaires, and “just a lot of ordinary people.” That’s to say nothing of the speaking engagements with NFL players and coaches, Navy SEALs, and government agencies. There’s Stoic merch, too: a memento mori medallion for $26, a ring for $245. Holiday’s project is straightforward: to boil down the work of ancient thinkers into pithy advice—philosophy as lifehack. “Have Your Best Week Ever With These 8 Lessons of Stoicism,” proclaims one of his video titles.

Along with tech lifestyle guru Tim Ferriss, Holiday is the principal evangelist of modern Stoicism, which is enjoying a vogue these days, especially among the Silicon Valley set. Gwyneth Paltrow’s personal book curator says, “Stoic philosophers are having a moment now.” A mini–book industry has sprung up around Stoicism that includes Holiday, Donald Robertson, and William B. Irvine. Author Elif Batuman took a Stoic turn while living alone in Istanbul. Susan Fowler, the software engineer who blew the whistle on Uber’s sexist culture, said she’d found the courage to come forward from Stoic teachings. Elizabeth Holmes held close a copy of Meditations as her blood-testing company crumbled. Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey is regularly taking cold baths. And there are the hundreds of thousands of people on Reddit and Twitter and Y Combinator’s Hacker News message board, ingesting bite-sized Stoic quotes about indifference and control and holding themselves up as a lonesome but formidable bulwark against “modern-day Oprah culture.”

An ethic of personal austerity has taken root in some of the country’s least austere zip codes. This development tends to be regarded as either a delightful incongruity, akin to Silicon Valley’s current fad for raw water, or a baffling hypocrisy. But what’s so baffling about rich people seeing the solutions to the world’s problems as a matter of individuals honing their own resiliencies? What’s so incongruous about a ruling-class philosophy that says that things are as they were fated to be, so just deal? In the hands of Holiday and its other contemporary popularizers, Stoicism offers both a guide to living and a tool for justifying the status quo, in all its inequalities—a philosophy less of the porch than of the marketplace itself.

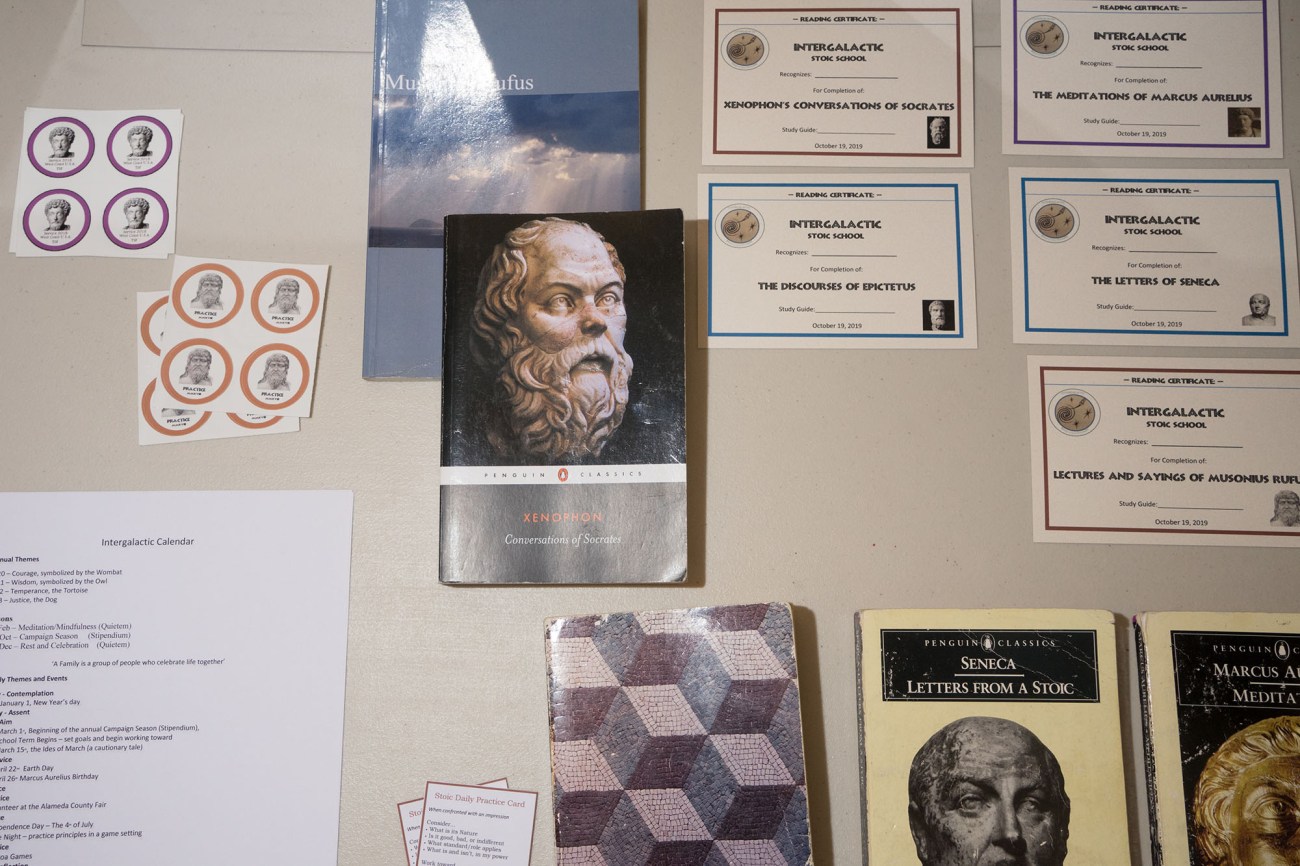

Any product needs a buyer. To sell Stoicism as self-help, there need to be customers desperate for change. At the Bay Area Stoic community’s annual Stoicon-X event in October, I meet a dozen or so adherents gathered around a table in a small library in Union City, California. The meetup features a presentation with photos of the galaxy projected on a screen, during which one member describes himself as lost amid the stars, unsure of what to do with his life. “There has to be an app for this,” he remembers thinking. He found Stoicism, a sort of algorithm for life. There isn’t much Seneca in his presentation, but there are a lot of tidbits of advice he calls “Stoicism Greatest Hits—Vol I,” such as “Love the life you live, live the life you love” and “The secret to having it all is knowing you already do.”

Modern Stoics mainly seem to read the modern Stoics. Wyn Robertson, an electrical engineer, came to Stoicism the way many others have: “I started getting those emails from Ryan Holiday.” New members at the Redwood Stoa, a nearby discussion group, are almost always “programmers or people who work in tech, just over and over and over,” John Knighton, an organizer, tells me. “They all have the same story: ‘I saw something by Ryan Holiday.’”

StoiconX attendees participate in an exercise.

James Tensuan

Outwardly, at least, Holiday makes for a funny champion of ancient philosophy. He has worked as a marketer for aughts-era fratiricist Tucker Max, and he handled media strategy for American Apparel’s sleazebag empire as its CEO, Dov Charney, faced accusations of sexual harassment. Both jobs informed Holiday’s 2012 book Trust Me, I’m Lying: Confessions of a Media Manipulator. (He has also written a sympathetic account of vampire plutocrat Peter Thiel’s sabotage of Gawker Media.)

Holiday found the writings of the Stoics at a West Hollywood safe-sex conference sponsored by Trojan condoms. Dr. Drew Pinsky was the host. Then a college sophomore, Holiday was reeling from a breakup. Pinsky recommended he read Epictetus, a former slave for whom Stoicism offered a way of rationalizing his suffering. It “hit me in the face,” Holiday says. Later, he was mentored by Robert Greene, author of The 48 Laws of Power, an “amoral” look at how power works, which remains wildly popular among entrepreneurial types. In 2009, a 21-year-old Holiday wrote a guest post for Tim Ferriss’ blog. In introducing the post, Ferriss, author of The 4-Hour Workweek, wrote that he’d found a “practical set of rules for better results with less effort.” Holiday’s essay was titled “Stoicism 101: A Beginner’s Guide for Entrepreneurs.”

Holiday has kept at it since then. His latest, Stillness Is the Key, is a shotgun blast of small stories about leadership. Among those who used Stoicism to excel, according to Holiday: Abraham Lincoln, Leonardo da Vinci, Malcolm X, Anne Frank, Marina Abramović, Napoleon, Ulysses S. Grant, Gandhi, Tiger Woods, Winston Churchill, and General Erwin Rommel. (A person who did not use Stoicism: Philip Roth.) In Holiday’s videos, we’re told over soaring music that Stoicism can help you “make progress” and “never panic”; it can “change your life” and “free you.”

Kevin Rose, the founder of Digg, compares the philosophy to asking, “How does this machine work?” Stoics, especially Aurelius, believe virtue is innate, part of our personal hardware. You know the answer; look inside yourself. Everything is about efficiency, about streamlining the self, dispensing with cumbersome and unproductive passions. “The pursuit of virtue is about the art of self-refinement,” Holiday says. His form of Stoicism is self-help rendered in the unique idiom of Silicon Valley, with its emphases on the individual and optimization and winning. “The ideas of Eastern philosophy, you have trouble making them work in San Francisco 2019,” he tells me. “But Stoicism fits.”

Gerry Castellino speaks during StoiconX.

James Tensuan

Stoicism can’t just be “something you do after work,” says Elizabeth Anderson, a professor of philosophy at the University of Michigan who focuses on inequality. It has to “pervade your whole life.” She writes in an email: “The Stoics taught that virtue was its own reward and that external material goods were worthless.” So why are the modern Stoics still obsessed with making money? “If they really wanted to live in accordance with Stoic philosophy, they would stop doing that, give up their mansions and private jets, and live modestly.”

It’s helpful to think of modern Stoicism in relation to other pet belief systems of the fancy classes. Anderson cites Adam Smith, the father of classical economics and the misbegotten patron saint of laissez-faire policy. “Smith is very popular among corporate leaders,” Anderson writes. “But this is mostly because they have not read him.” Greed is good, the invisible hand of the market is unerring, the rich are virtuous: These ideas are the fruit of a reactionary misappropriation of Smith’s ideas. “Smith said none of these things,” Anderson writes. “Mostly the opposite!” (Smith was also assumed to be a Stoic who was indifferent about wealth inequality—not true.)

John Dewey and other American pragmatists saw philosophy not as a search for truth but as the work of humans making up ideas to explain themselves. “Knowledge,” Dewey wrote, “is an instrument or organ of successful action.” It happens over and over throughout history, especially among the rich—the people most in need of an alibi. Social Darwinism was a Gilded Age phenomenon; actual evolutionary theory was twisted until it could be used to argue that destroying others for profit was simply the natural order of things. All of us pick and choose from the notions floating through the culture to justify ourselves and create a personal narrative. But the ideas that powerful people use to exonerate themselves become, with the help of translators like Holiday, a kind of common sense for the rest of us. In an era of massive inequality, it was only a matter of time before someone found a way to rebrand the oligarchs’ retreat from their social obligations as timeless, hard-edged virtue.

We’ve witnessed something similar before with Stoicism. In the post-Reconstruction South, Walker Percy saw all the ways Stoicism was being used in the name of maintaining power. He argued that the “old Stoa” had more of an influence on Southern values than even Christianity. Southern white people, Percy realized, were outraged on Stoic grounds at “the Negro’s demanding his rights instead of being thankful for his squire’s generosity.” Things are as they were fated to be, so just deal.

Holiday calls Percy a favorite author. But he doesn’t seem to agree with Percy’s insight that Stoicism is useful as a means of shoring up privilege. In fact, Holiday doesn’t believe privilege conflicts with Stoic precepts. “Extreme success or extreme wealth is not at odds with Stoicism or with virtue,” he says. “Seneca’s word is that it’s a ‘preferred indifference.’ It’s better to be rich than poor. It’s better to be tall than short. A Stoic would—a true Stoic would—be able to handle either one. But if you had to choose, I mean, wouldn’t you rather be successful than not successful?”

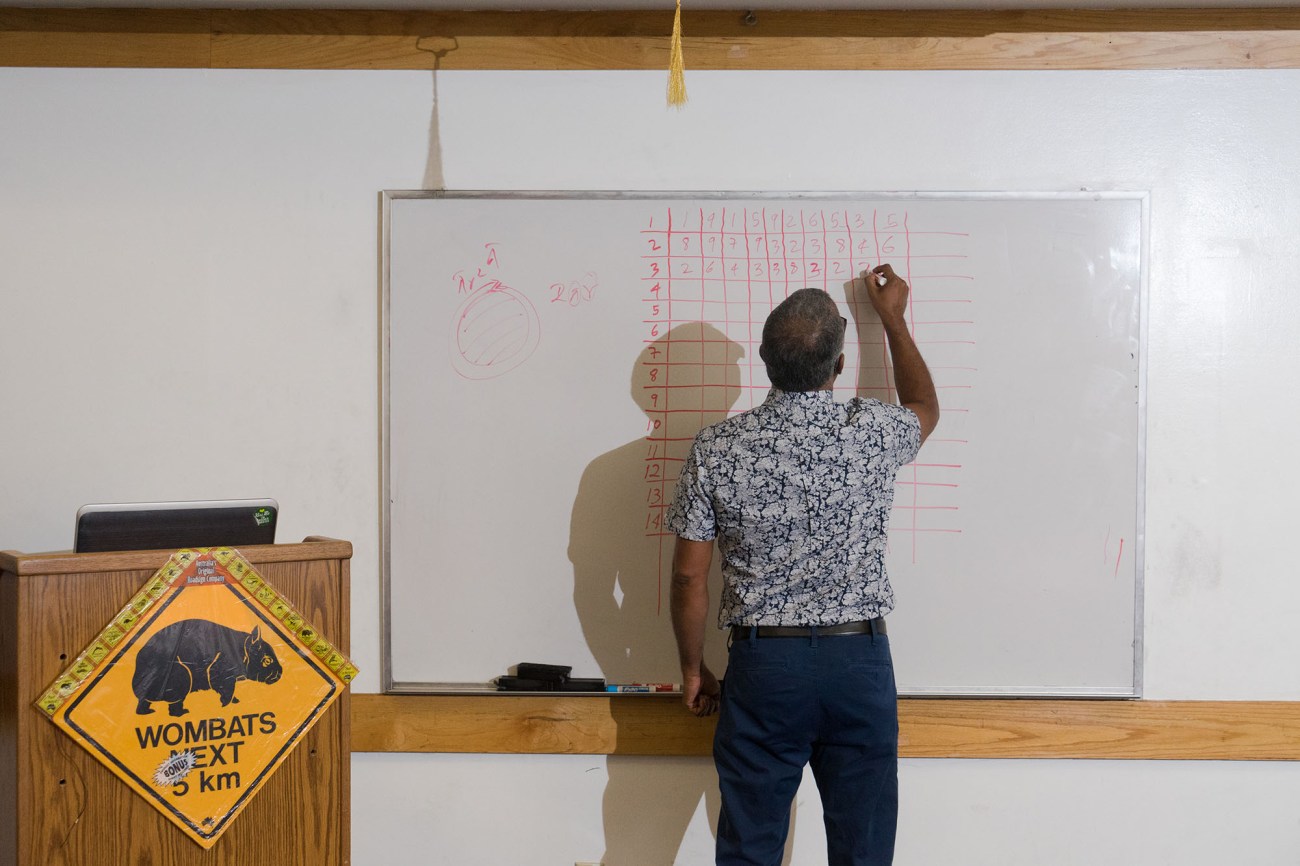

Gerry Castellino writes down the first 100 numbers of Pi during StoiconX.

James Tensuan

Not long ago, the New York Times puzzled over what it called the “Jekyll and Hyde-like phases” of Holiday’s career. But in truth, the job is always the same for Holiday, whether he is concocting stunts for Tucker Max, running interference for Peter Thiel, or dispensing Stoic-inflected woo. Holiday is doing brand management for the amoral elite.

Not all Stoics have turned the old texts into a manual for winning. On a recent Sunday morning, I attend the small monthly meeting of the Redwood Stoa in a botanical garden in the Berkeley hills. One of the members, Seamus O’Donnell, grumbles about the “gamification of Stoicism,” adopting the voice of a video game announcing a new level: “You have reached sage!” “You won life,” another participant in the circle says.

“Sometimes I’m really worried about the commodification of this philosophy,” O’Donnell goes on. Simon Gunner, a co-leader of the Redwood Stoa, is too. “If it’s helping them become wealthier or better businesspeople,” he says, “that’s where the hypocrisy would come in…The contradiction definitely existed in Seneca. It lives on.” Stoicism was now just another thing trying to draw a crowd, alongside the fire eaters and sword swallowers.

A botanist, Gunner ends the meeting by having us look up at the redwoods, and then he reads a passage from Seneca. It’s about the beauty of finding yourself in “a grove that is full of ancient trees.” Here in this public park, the marketplace seems very far away.

The price of the Memento Mori Signet Ring has been updated following print publication to reflect a price increase.