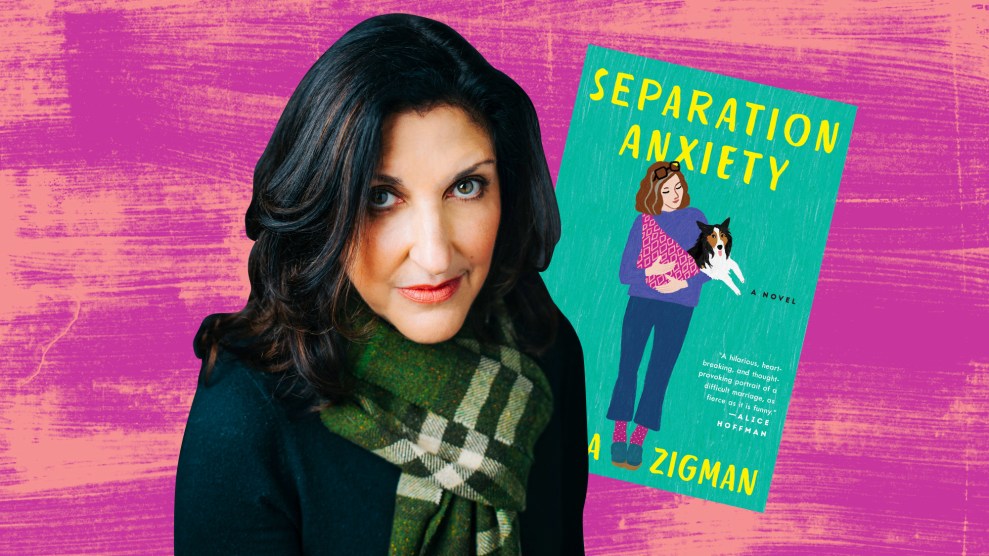

Book jacket: Ecco Books, photo: Adrianne Mathiowetz and Mother Jones illustration

Just to dispense with personal connection at the onset: Laura Zigman and I have been friends for a couple of decades. We met in New York, when she was a publicist for Random House and I was a reporter. After years of carrying sharpies and additional physical and psychological ego-bolstering materials to keep Big Deal Authors happy, Laura moved to Washington, DC, to work in what passed for a normal job at the Smithsonian. She figured that these were the circumstances in which she could finally finish the novel that had been her constant companion for five of the 10 years she had worked in New York, though she had doubts about whether it would find a publisher or an audience.

As it turns out, Animal Husbandry—her story of twenty-something heartbreak explained with insights from, well, animal husbandry—went nova. A Random House imprint published it in 1998; the book was sold in about 22 countries; and was turned into the 2001 film Someone Like You, starring Ashley Judd and Hugh Jackman. Laura became one of the authors heralding a period of fiction where, as she puts it, “a lot of single women who were not getting married until later and who living in cities and dating were all writing in a kind of collective consciousness.” She joined authors like Helen Fielding (Bridget Jones’ Diary) and Candace Bushnell (Sex and the City) as exemplars of the “chick lit” genre.

All that success seemed to preordain the fantasy life of anyone who has ever labored in a writing program somewhere: She could quit her day job and crank out bestsellers every couple of years. She would be able to support herself and her family comfortably. She would never have to worry about getting stuff published or being an unknown loser again.

“I guess in the back of my mind,” she told me, “I always knew that at some point the fun would stop.”

She wrote three more novels; each one tanked. She moved with her husband and their young son to her hometown of Boston. Her parents became ill, and she cared for them until they died. She had her own bout with breast cancer. In a recent essay for the New York Times titled “Caring for Two Generations Almost Cost Me My Career,” she explains, “Stress and exhaustion and depression had given me a fairly severe case of writer’s block, and I had pivoted to ghostwriting work to supplement my husband’s teaching salary and pay the mortgage. Helping other people write their stories had become easier than writing my own.” But helping other people write their stories exacted a creative price.

And then, something happened: She reclaimed her voice. Now in her fifties, Laura has a new book that again captures the challenges of her demographic—this time smart, once-successful middle-aged women who are having trouble with their lives but love their dogs. Separation Anxiety, published this week, is about a writer who enjoyed huge success with her bestselling children’s book but has now sunk into anonymity, writing chirpy advice for a site called Well-er, while she worries about money, grapples with her son’s adolescence, watches her closest friend die slowly, and endures a marriage that feels like it would end if they had the funds to divorce. This character finds remarkable comfort in wearing her dog in a baby sling. In anticipation of publication, Separation Anxiety got attention. USA Today, among others, included it in “this season’s must-read books.”

Novelist and children’s book writer Alice Hoffman described Separation Anxiety as “a hilarious, heart-breaking and thought-provoking portrait of a difficult marriage, as fierce as it is funny…My advice: Start reading and don’t stop until you get to the last page of this wise and wonderful novel.” In other words, it looks like Laura is back in the game in a very big way.

But I wanted to talk to her about those 20 years when she wasn’t. So we caught up by phone a few weeks ago.

Let’s first go back to the halcyon days of Animal Husbandry. Can you describe how all that success felt?

That was just a completely shocking experience. I had come from a family that did not send me to New York thinking I was going to do anything but have a job with benefits. That was the whole thing. I never thought, “I’ll leave college and then become a writer.” I just didn’t have that kind of confidence. And so when that kind of, I hate to call it success, but when that happened, it felt amazing, because I had never ever had to face the thought that anything like that would ever happen.

Why do you hate to call it success?

If you’ve come from the kind of background I come from, you just know there’s the flip side or there’s a swing. So if you have this great success, eventually it will turn.

You left DC and moved to Boston. It seems as if things started to take a turn then.

I think I moved back thinking I was going to get this great do-over. I never liked where I was from. I never felt happy where I grew up, and suddenly I was living one ZIP code digit away from house I’d grown up in. I thought I was different now. I thought my parents would be different, and of course they weren’t and I wasn’t. A certain amount of regression took place. I got depressed, and my career was starting to take a downslide, which is really normal when it comes to publishing. Certain things don’t work out. Certain books are optioned and those options don’t—nothing comes of them. And everything that could’ve gone wrong started to go wrong. Then it’s a snowball effect. When you’re in your forties, people start to get sick and stuff starts to happen. I got to a point where I wasn’t really able to be creative. And when you have a career that’s dependent on creativity and faith in your creativity, it can really stop all of a sudden.

You also got sick, right?

I was diagnosed with breast cancer. It was very early. But I had a lot of surgery, and I ended up watching a lot of television. This was 2006 and 2007, there was no Facebook, there was no social media really except Myspace. So it wasn’t like you could sit around and look at everything. TV was still the thing. One of the shows I ended up watching was about a matchmaker on an A&E reality show. And I think I blogged about her. I really liked the show and it turned out she wanted to write a book. That’s how I moved into ghostwriting. I couldn’t really do my own work anymore. I’d just come to a point after my fourth novel where it was kind of a bust and I didn’t have a lot of confidence, and ghostwriting seemed to be a great move because you still have your skill set, but you don’t have to come up with the material. It’s like a job. Eventually I was able to earn a living writing other people’s stories and not my own.

But what were the tradeoffs in terms of your own perception of yourself as a writer?

The most obvious and the biggest one is that you lose your voice. When you’re ghostwriting, you are writing in their voice, you’re telling their story, and you become invisible. And when you’re writing fiction or when you’re writing your own work, your voice is everything. You have to sublimate when you’re ghostwriting. The more I ghostwrote, the less voice I had on my own. I just felt disappeared, completely disconnected from the writer I had been. The person who identified as a novelist was just gone. It felt like it almost had never happened. I had gone from being someone who had four novels published and a movie, which gives you a certain amount of credentials in the business, to like nothing. I’d go into my local bookstores and nobody was like, “Oh, you wrote Animal Husbandry?” It was like completely gone. And it wasn’t that I wanted that kind of recognition, but it just always struck me that, wow, it’s like two different lives.

When you look back at the process with your earlier books, and now being older and more experienced, what was different about the way that you wrote Separation Anxiety?

When I wrote Animal Husbandry, I was writing it in my spare time with my full-time job. And so it took me over five years to write. I wrote it not having an agent, not having a publisher, nothing. In one way, it’s hard to do that because you don’t know if anything’s going to happen with it. But there’s a great freedom because no one’s ever going to see it, so hey, just do it. With the subsequent novels, I always had a contract, and I had a measurement of success or failure in terms of sales figures and reviews. And then my career disappeared. When it was time to write the fifth novel, no one was waiting for it. No one even knew I was writing it.

It’s hard in one way because you feel like no one cares. But there’s that freedom to just do what you want to do. This one took me about three and a half years because I was doing it in between ghostwriting projects. I just didn’t have the faith. I would do some pages and really feel like I was making a start, and then I would look at them or my husband—he’s a writer and a really great reader for me—would look at the pages and he’d be like, “ah, no.” And it wasn’t cruel or mean or undermining. It was like, you can do better. I got what he was saying and I just went off to just try to do the best that I could. It took a long time to feel like I was making the book I wanted to make and to write it in a way that I wanted to write it.

I didn’t want the humor to be cheap humor. I didn’t want the jokes to be at other people’s expense. And I think that had a lot to do with what was happening in the world. Just the sense of wanting to be kind in a way, wanting to be funny, but also wanting to be sort of compassionate, knowing that everybody is struggling. And wanting it to be like a more compassionate kind of humor. And I think that’s what the silver lining in a decade or more of misery is.

When were you ready to jump off the cliff and share it?

I had been out of the game for awhile, and I needed to get a new agent, which began the miserable process of being rejected. I was rejected very quickly by three agents right off the bat. Then I was told to try a big agent at a big agency. Within a week, I got an email from her, and it said something like, “Oh my God, love your voice. Big fan of Animal Husbandry, blah, blah, blah.” And she basically went on to say, this is not the book to resuscitate your career. I wonder if she actually said it’s cringe-worthy. She basically begged, please do not publish this book.

I wanted to just die, reading an email like that after trying so hard. I just thought, “Oh my God, this is never going to happen.” I called my friend who is in publishing, and I told him what happened and said, “You have to tell me if this book is terrible. You have to be honest with me.” He told me it was good and that I should try another agent. Two weeks later, I get an email that essentially says the exact opposite of the one that crushed me.

And so my point is not to brag that I got the great email, but to say this is what it’s like, where you get two completely different emails in the span of two or three weeks. One says it’s a disaster, begging you, don’t publish this book, it’s so awful. The other one is saying, oh my God, this is the book, I’m dying to read the book, I’m dying to share with my female friends, blah, blah, blah. How do you justify those two completely opposite opinions? Somehow you have to not curl up in a ball after the first one. I knew when I read that first email, that I didn’t agree with her. I’m not going to say I was not completely unhinged by it, but I also sort of felt like, no, she’s wrong. Or she’s just not necessarily right. When you’re writing your own stuff, you have to figure out when to listen to criticism because people can make you better. And you also have to know when to say that someone is wrong, and you are going to trust your own sense of things. And that’s really hard to do because I’ve been wrong so often.

Was there something to be gained from those miserable years in the wilderness?

When you’re in the wilderness, you just don’t really believe it’s ever going to end, and you somehow have to move forward anyway. After nine years of not publishing anything, not writing a novel, it took nine years for me to say, okay, I want to try again. And then it took another few years after that to finish. And it could have turned out where I didn’t sell a book. But the wilderness gave me my main character and gave me all the plot points, because even though it’s obviously a fictionalized version of things that I’ve experienced, those things are just imprinted on me, all the loss and all the little moments of joy. And I think the big moments of loss—those moments of joy are just so much more meaningful, because they’re in relief against those other things. So many people get to this point where they’re struggling and they don’t believe they’ll ever get out. I don’t know if I’m out for good, but I’m out for now and that feels triumphant, this little step back into what I’ve missed for so long.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.