“Traplanta” is a living portfolio of photographs taken by Willis, a mononymous, 36-year-old Navy reservist and art student who lives in Marietta, about 30 minutes north of Atlanta. He describes his work, which he posts on Instagram under the handle @_traplanta_, as “Southern vernacular, urban reportage, fine art journalism.” The images he captures range from day-glo glimpses of strip clubs to resolutely matter-of-fact portraits of neighborhood drug corners, each photo accompanied by an archly oblique caption. Take the photo of the bottom half of a person fanning out more than 18 $100 bills on the ground. Only a pair of dark hands, legs, and bright white Air Force 1s are visible. The photo is juxtaposed with a bit of history, gleaned from Wikipedia: “James ‘Honest Dick’ Tate was a Kentucky State Treasurer, so-called due to his good reputation. In reality, he had quietly misappropriated over $250,000 ($7 million in present value) from the treasury. In 1888, he fled the state with a sack of gold and silver coins and was never seen again.”

The photos are addressed to two audiences at once, demanding that each scramble its subjectivities: Willis wants people in the hood to see their environment through fresh eyes, and he wants people who don’t live there to see it with the matter-of-factness of someone who does.

Shortly after the arrival of the coronavirus, Willis began documenting the pandemic’s effects on local dealers, who’d grown desperate amid the cratering of the drug trade because of shelter-in-place orders. Soon, too, he was taking photos of the uprising following the killing of George Floyd, which is how he wound up spending two days in jail for violating curfew.

Here is Willis in his own words, with some of his work from the lockdown through the uprising, a time when all of America’s subjectivities got scrambled. —Jamilah King

I got a homeboy who lives in Stone Mountain and there was a big strip club event going on. I asked him if he wanted to go to the strip club with me. He said he did. I told him: “I was at a protest yesterday, and they were, like, burning shit. I want to get a couple more pictures of the protest and then we can go to the strip club.” We were gonna cut through the city, take pictures, hop back in the truck, and go to the strip club.

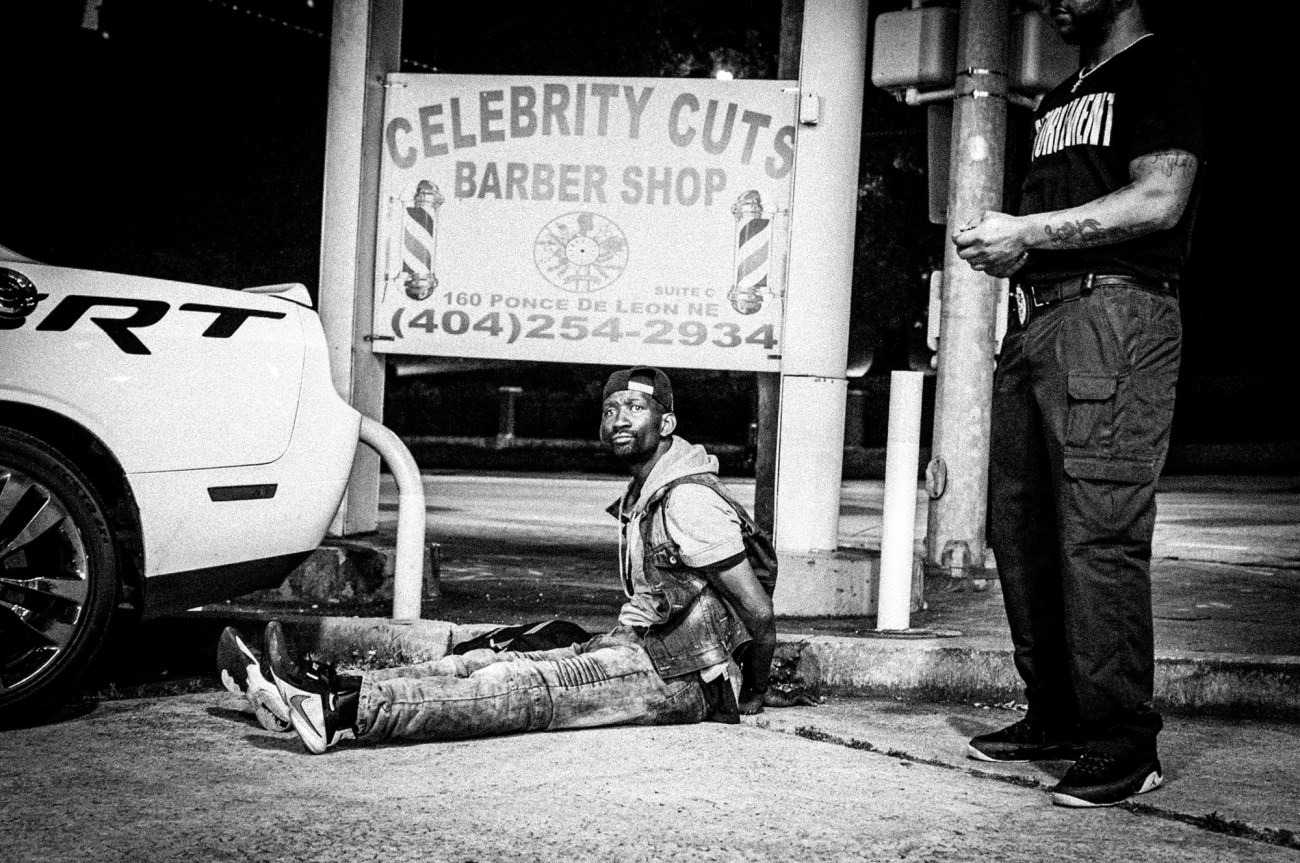

We get downtown. We park the truck. I see some cops and they’re arresting this guy. They let me take a picture, and then some cops say, “It’s like it’s real hectic over there, you should go down that street.” We walk down that street and there’s literally like, 20 cops out there. They grabbed me and arrested me for breaking curfew.

It was a booby trap, I got totally bamboozled. They took my camera, they took all of my stuff, took my phone. They took us to the paddy wagon and then to jail. And we sat there and it was just a whole bunch of bullshit. They didn’t have enough blankets and masks for everyone, and the food was terrible. Folks were fighting and screaming in their cell, and at night you could hear them sharpening shanks on the ground. It was utterly insane.

Some of the dope boys I know, they got arrested. They were like, “Oh shit! What you doing in here?” I was like, “Taking pictures, bruh!” And they were like, “We sell all this dope and they got us for curfew violations.”

I was in the service for 18 years. My first job in the Navy was as an electronic technician, which is somebody who keeps missiles from hitting your boat when you’re actually in war. I did that and they teach you under a lot of duress how to stay calm in the situation. When you’re working, a missile could be flying literally toward the ship and you have to do everything right. I did that for about three years. And then I spent time in a couple shitty deserts doing other stressful things that could have gotten me blown up. After that, I got sent to go fight pirates off the coast of Africa and I did that for five years. And then I came back home.

My biggest issue was, I had dealt with things that were so incredibly violent that all I knew was this heightened state of violence. I really had to teach myself not to give a shit because at the end of the day, nobody here has dynamite strapped to their chest. Nobody here has a car loaded down with C-4.

When you realize that, you realize not many things fucking matter.

I started “Traplanta” about two years ago. I had a photography assignment where we were supposed to go out and take pictures on the street. I did what everyone does and took pictures of homeless people and fire hydrants, stuff like that. When I brought it to my professor she told me point blank the work was terrible. She told me I should take pictures of things that I know. I told her the thing I knew best was the hood—it was where I was raised. She told me to redo the assignment, and I did, and I took pictures of dope boys and strip clubs and just “the trap.” She really liked the pictures.

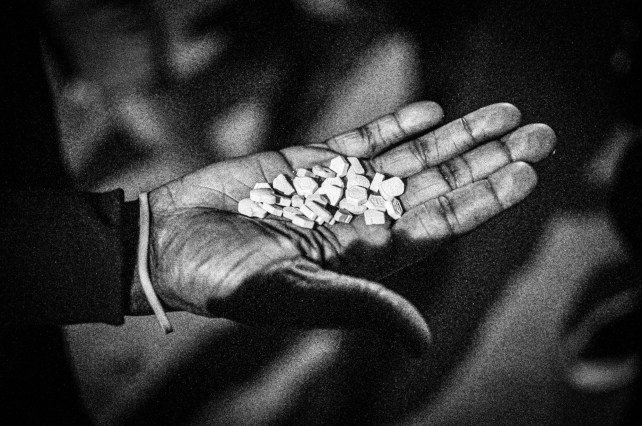

A couple of my friends sell crack and heroin, and my cousin sells weed. When corona hit the scene, everyone outside the trap was terrified. People stopped buying crack. The block became dry, and here you had all these people who were making $1,000 to $3,000 a day now making $40 and $60 a day. So I wanted to document that lull in the dope game. Imagine being a boxer and no longer being able to fight. It’s the same for a drug dealer. Imagine the money, the excitement, the flashiness—and then boom! It’s gone. What do you do when you can’t do what defines you anymore?

The lull’s over now. I was just talking to a dealer, and they said someone just bought $2,000 worth of crack off them. I know motherfuckers who pooled their stimulus checks and bought a kilo and probably quintupled their money.

I don’t force-feed a narrative. I let viewers build their own. This is reality, and it’s multifaceted. It’s like an onion—there are multiple layers to it. Dope is part of it, but these people, they got kids. Like my homeboy—he’s got like two houses. He drives a basic-ass dadmobile, and he sells dope. His kids think he does construction. He leaves the house in a hardhat and a vest, says he loves them, kisses them goodbye, and then drives off and sells dope all day.

Everybody got a hustle. Everybody just trying to survive. I guess that could be said for anybody anywhere, but in Atlanta people just respect that you have to hustle.

“When Corona hit the scene everyone outside the trap was terrified. People stopped buying crack. The block became dry, and here you had all these people who are making $1,000 to $3,000 a day are now making $40 to $60 a day.”

“I wanted to document that lull in the dope game. Imagine being a boxer and no longer being able to fight. It’s the same for a drug dealer. Imagine the money, excitement flashiness and then boom! It’s gone. What do you do when you cant do what defines you anymore?”