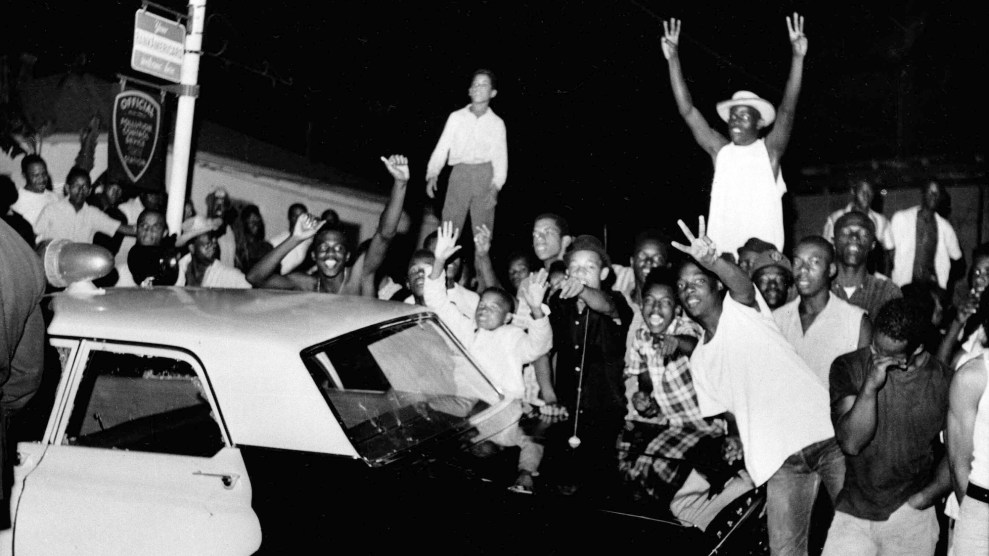

The Watts uprising in 1965. "I once promised my oldest daughter I would never talk about the fucking ’60s again," Mike Davis says. "But the problem is that so many of the struggles and the issues are exactly the same issues we're facing today. AP

Mike Davis hates being called a prophet. If the 74-year-old social historian, author of proto-doomer urban theory classics like City of Quartz and Ecology of Fear, seems to have an uncanny ability to see America’s futures, it’s because he draws so fluently on its past. Davis possesses an encyclopedic knowledge of leftist history and land use in this country—particularly in Southern California, his birthplace and home. Recently we spoke with Davis over Zoom about his latest book, Set the Night on Fire, co-authored with Jon Wiener, about 1960s radical politics in Los Angeles.

Davis was on the scene for events like the Sunset Strip curfew riots, and he witnessed firsthand the patterns of police brutality against protesters that feel so relevant today. He also saw how the activism and youth culture of the era set itself against repression of different kinds, from the curfews and cops to draft boards and closed beaches. (Why did LA forbid beach bonfires? As the book explains, the cops were haunted by the radical specter of unsupervised teens getting together at night.) Set the Night on Fire is a sort of bequeathal from one generation of activists to another. Davis told us he and Wiener wrote the book to inform young people about the hidden history of LA and the fatal mistakes made there by radical movements in the 1960s, in the hopes that today’s radicals might succeed where yesterday’s failed.

Davis talked to us from his home in San Diego, where he is quarantining with his family and detailing the horrors of the pandemic in a daily e-mail newsletter to colleagues called “Plague News.” The transcript has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Molly Lambert: Since the last time we saw you there was a pandemic and then the uprisings. Do you feel like this is comparable to any other moments in history?

Mike Davis: It’s a bit like the 1918 Spanish Flu combined with the Great Depression. I mean, Americans went to bed one night in early March and woke up the next day to find out they were living in 1933. The difference of course, is the policy has played a far greater role in this case than it did in 1918 even with the Great Depression. Hoover actually was extremely energetic in dealing with soaring unemployment after the stock market crash. What he did wasn’t sufficient. But he was a famous engineer and a famous administrator of relief. So there’s no comparison between Trump and Hoover. Trump has become the principal vector of coronavirus in this country, one might say even in the world, because of the way that others like Bolsonaro in Brazil, Duterte in the Philippines followed his example.

Jonny Coleman: Do you think the ongoing economic precarity—do you think that we’re primed for having the right material circumstances for a major upheaval of power? Do you think the racial justice [uprising] and the evictions and the economic crises that everyone but the wealthiest are going to feel have the potential to bring us together?

Speaking as a historian, I don’t see any alternative path for capitalism to resolve this crisis. This isn’t a conjunctural crisis. It’s a crisis within a complex of crises: the failure of capitalism to generate jobs and sustainable incomes, making a large minority of the human race surplus and therefore disposable; the blockage of revolutionary advances in biodesign in medicine by the private sector government policies, preventing that to be translated into public health; the fact that the Republican Party has enjoyed such enormous success in blocking any action on climate change; and the fact that we’re in a world that becomes more dangerous, day by day. The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists points out the risk of nuclear war is higher in today’s world, according to them, than almost at any time during the Cold War, with the Cuban Missile Crisis maybe set aside.

The world’s descended into an age of chaos. And the policies that have been adopted particularly against poor people in poor countries amount to a sentence to genocide: people forced to migrate because of wars that generally have been spurred by foreign interventions, American interventions; or migrating, like in the case of Central America, [because of] unprecedented droughts and crop failures. We build walls. Europe deliberately lets people drown in the Mediterranean. The US seeks to control as much of the potential vaccine supply as possible to prevent it from reaching poor countries. We could go on and on.

And these policies all point in a very determined and clear direction, which is that there are probably a billion and a half people, maybe more, maybe 2 billion, in the informal working class who have simply been triaged already in advance. So the fate of a very large minority of humanity has been determined now. And that’s more important than almost anything else. Coronavirus is just part of the crisis. But there’s an overall crisis of human survival and sustainable urbanization.

Although Marxists are often accused of proclaiming every recession to be the Final Crisis, I don’t see any way out of it. In 2008, the decisive thing was China’s ability to pump an enormous amount of money into infrastructural investments. And by restoring growth in China, it restored growth in Europe. For instance, China is Germany’s largest customer. And although we’re still living in the debris of 2008, China was able to lead the world out of it. And I don’t see the possibility of that today. China itself is facing huge problems. And America of course is dragging much of the world down. And you have to ask yourself: What decisive steps will Joe Biden take that will really refloat the economy? I don’t see it there. He will simply administer economic decline a bit more humanely than the monsters who currently occupy the White House.

ML: It’s like everything is sort of lining up in a way people are seeing that all of these issues are inextricably woven together, which is something I thought came across in your ’60s book. How can we get people to all work together?

We need to face certain facts. It should be obvious—and I must say I was critical of Occupy Wall Street in this sense, right from the beginning, this idea of the 1 percent. In the elections, over the past hundred years where Democratic presidential candidates have had the largest margin of victory, still, the Republicans are able to count on 37 to 41 percent of the vote. Alf Landon in 1936, at 37 percent of the vote. Barry Goldwater got almost 39 percent of the vote. Trump’s popularity ratings are still about 40 percent. But you need to ask yourself—why this constant percentage in American political history? What does it say, particularly about the upper middle class, the local country club elites? Today the hedge funds and private equity people are a very large base in this country for conservative politics. This was true in the 1930s. It was true to some extent in the ’60s with the Goldwater–massive white resistance brigade. And it’s true today. So when we talk about bringing people together, we shouldn’t be talking about it in some vague populist sense, believing that there is this great basis of unity. It’s the 60 percent that we’re talking about and creating a class unity that is based on full recognition of structural racism and systemic discrimination.

The elements are there to bring that together. Material conditions—downward mobility, which has increased tenfold since March—aligned with the universal perception that civil rights were being driven back in every quarter have created a powerful material base to transform young people of my kids’ generation, my kids are in high school, into a potent force for radical change.

But the fact that it took the form of the Sanders campaign also brought with it a fundamental contradiction. The Sanders campaign said that we can both be inside and outside. Most important is the movement in the streets and the workplaces, and political work will be the expression of that, and we can maintain both these things. Well, we’ve seen since Bernie withdrew from the campaign that that wasn’t the case. Tens of thousands of activists were just left stranded while the progressive Democrats were negotiating with Biden in organizing for the election. This would have led to a tremendous sense of defeat and demoralization except for Black Lives Matter, which suddenly created a terrain and an impetus for young people who’d been active to return to the streets and return to activism.

I don’t think I have many illusions about electoral politics, but I was stunned when the Bernie negotiators [before the Democratic National Convention] refused to stay solid behind Medicare for All at a time when it’s never been more obviously popular in a distressed country. It was a fundamental demand. We’ve seen the delegates finally revolted. Some 600 of them, including Biden delegates, refused to surrender on this issue. But the battle came too late, once the negotiators had surrendered that.

So this raises very difficult but at the same time very traditional issues. Has elected power ever strengthened mobilization and struggle at the level of the grassroots, at the union base, in the communities, and so on? And the answer that was outlined by the German Social Democrat, Robert Michels, 115 years ago after the German Social Democrats won a huge victory in the Reichstag—the answer he gave is no. And this is something that has always haunted the left whenever it’s trying to combine electoral strategy and class struggle in the workplace or mass movements for, for instance, racial equality.

It remains to be seen what kind of capacity there is for struggle in a Biden administration. On the other hand, we should not pretend that this crisis can be managed, because it’s a structural crisis of a different kind from all the postwar recessions or economic crises—it’s far more profound. And one thing that should be obvious is, we’re going to face increasing levels of social violence. And this is the main thing I think most people on the left are really not prepared for. Romantically maybe: If they’re going to start shooting we’ll start shooting back. It’s not going to be that way at all. Now the digital repressive powers are so much greater than in the past, but also because there is really an active neo-fascist movement. Assuming Biden wins in November, what do you think their reaction is going to be? We’re gonna see a whole number of incidents and that will set the tenor for this historical period that follows. So, in my mind, this means we have to move beyond the Debsian model of left mobilization and see the need to return to a more democratic version of Leninism: the importance of an organization, of organizers capable of making strategic and not just tactical decisions in interventions. Because it’s a bit like the Game of Thrones—the winter is ahead of us. And we have to begin to try and imagine what that will be like and what it will entail.

But again, that failure of the Democrats to do even the simplest things—I mean, Elizabeth Warren, to her credit, did advocate an excess profits tax. Socialists need to advocate that the entire essential infrastructure, which now includes all the social media, it includes Amazon and so on—we should have to take those businesses and socialize them. Socialize Amazon. These should be non-negotiable to me.

But the elementary thing I was taught as a young radical from older radicals is that the role of communists is to raise the question of property in every struggle. Other people, other progressives who are good left comrades, won’t see that. This was another criticism of Occupy. It focused on inequality when the real question is economic power, the democratization of economic power. This is the core question always, of human rights versus large-scale private property. We need greater clarity about that. And that comes from, among other things, understanding historical socialist and communist movements in politics in different situations.

JC: The last time we talked, you said you had read every issue of every edition of the LA Times.

Before the present period, yeah.

JC: I’m just curious if you’ve been following what’s going on in LA. To connect to your book on the ’60s, it seems like there’s an opening for a new leftist press in LA, and there are a few websites and other publications that have recently started to break big stories. One of them was a story about some LA sheriff’s department people throwing an indoor party in Hollywood.

The sheriff’s department is the most dangerous cancer now in urban politics. This revelation about the Compton substation, not really a revelation—I mean, that substation’s been notorious for 60 or 70 years. But the revelations about a gang there that awards points and membership based on brutality, or for that matter, the murder of civilians, should lead us to kind of a broader concept than just focusing as we always have on the LAPD. And we need to look at the sheriffs particularly because the sheriffs have a community. They have no investigative journalistic coverage because all the small papers have disappeared, as well as the so-called underground press. So if you live in South El Monte or Bell Gardens or Hawaiian Gardens or something like that, who’s looking at your local politicians? Who’s monitoring the police? The coincidence of that and the fact that so many not only unincorporated areas but some of the incorporated areas use the sheriff—the combination of these few things has made them totally invincible in the field.

And of course we must look at the whole criminal justice system, moving beyond the cops obviously to the DA’s office, to the judges, and to the legislature that sets policies to allow the police to go out and abuse and kill people and to lock people away. I’m not aware that the Democrats will ever give the blanket amnesty that we all feel is absolutely necessary in the context of the war on drugs. Yes, there have been some reforms, but they don’t go anywhere near far enough. We need a full-scale blanket amnesty. And beyond looking at the death penalty, we need to look in California at life imprisonment. There’s a movement about that, and there have been really heroic strikes by prisoners over issues of solitary confinement and life imprisonment. I mean, we still haven’t repealed the three-strikes law.

So I think it’s the natural trajectory of Black Lives Matter and associated struggles to broaden out and look at the entire system and structure, as well as the interest involved in sustaining super-incarceration and the violent injustice of policing. It’s a social miracle that Black Lives Matter has put forth the issue of the police, do we really need them? These are questions I never thought would become part of a large-scale public debate in this country. I think it’s due to the enormous creativity that BLM has shown.

In my writing recently my real focus has been to build a broad movement over workplace safety. There’ve been hundreds and hundreds of wildcat strikes and job actions by workers. And in individual cities you find left groups of all kinds, including DSA chapters, supporting the struggles, but nothing like the kind of national movement that needs to be built. The issue is ongoing. I wrote that we’re facing a situation where essentially millions of American workers have had to make a Sophie’s Choice over the safety of their family and the necessity of paying the bills and the rent.

Tens of millions of people had to make agonizing choices. And what advice have they received from anybody else? We’re only beginning to see the real nature of the cruelty and pain and crushed hopes that have happened over the last three to four months. It’s far deeper, widespread, and more profound than any image you can see of it now. That’ll become clear over the next few months. We’ve seen absolute immiseration, to use a Marxist category—not relative immiseration, absolute immiseration of the kind that hasn’t been seen since probably 1938 in the second Great Depression.

ML: I learned from reading the book that the LAPD’s invincibility clause dates back to the 1930s, when they put the thing in that their own internal board would always review the murders.

I did some interviews with Jon over the anniversary of the Watts rebellion. So I was rereading the first six, seven months of 1965. One of the events that occurred before the uprising was this public hearing of a cop named Mike Hannon. Mike Hannon joined the police force in 1957 or 1958 in order to pay his way through legal studies. He was an active member of the Congress of Racial Equality in Los Angeles. He also came from an old socialist family, and he participated in sit-in demonstrations and so on on his own time. But he was put on trial. He makes this incredibly stirring case that appears on the front pages of the newspaper for two weeks. You know, a very workable and serious plan for total civilian control of the LAPD.

I once promised my oldest daughter I would never talk about the fucking ’60s again. But the problem is that so many of the struggles and the issues are exactly the same issues we’re facing today. There are very few things where you can say the issues have been somehow resolved—issues of rotten overcrowded schools, police violence, discrimination in housing and the workforce—and the relevance of the ’60s is precisely that fact.

Just before the wall fell, in 1988, I was in Frankfurt, and I got invited by the largest metal union in the world, IG Metall, to visit their education office. They showed me this institution they’d built, which was a summer school, where basically shop stewards go. They negotiated into the contract to take three weeks off and go with their families, so the wives or husbands would not be left at home to take care of the kids. What they did at the summer school in a very sophisticated way is they refought the great battles of German history. They’d go back to the 1918 revolution or look at 1932, revisit it.

So in that sense, the 1960s book is a bit of war game which you play, not for the sake of understanding history better, but for the sake of understanding our current situation. What lessons of the past are relevant? What mistakes should we avoid this time?

JC: Do you think there are big mistakes that we can avoid this time around and what are they?

One mistake that in a sense we’ve long learnt the lessons of, if not explicitly, implicitly is that in the ’60s, the entire left, whether you’re talking about the Black left or the anti-war left, were watching liberal Democrats, including the idols of Democratic liberalism like Adlai Stevenson, Hubert Humphrey, Pat Brown, and they’re either directly administrating or supporting genocide in Southeast Asia and sacrificing the good part of the Johnson administration.

Johnson is no tragic hero; he’s a war criminal. But his real passion was restarting the New Deal and addressing poverty in the country. And of course, he’s the only conceivable Democrat who could have gotten the Voting Rights Act through. So we’re watching all these guys sell out their best value, murder their better angels, so to speak. We saw them as the main enemy, and we didn’t really understand, or we seriously underestimated the threat of the right, the way the right would transform. The liberal Republicans—the Rockefellers, the John Lindsay types—were in steep decline. And it’s the Goldwater types and their narratives that were on the march. So we completely underestimated that.

I had a long debate with Dorothy Healey, the most influential person morally and intellectually in my life, and we fought cats and dogs over the issue of the need to vote for Democrats. Dorothy was a Popular Fronter. She was very insistent that you vote for Democrats if only for one thing—to prevent Republicans from nominating judges. I now see she was right.

Other things were almost unavoidable given the high and constant degree of repression that existed. And a lot of it was exclusively intended just to tie up, to paralyze radical movements. Evelle Younger, who was DA, issued 1,730 felony charges against some Black students in Northridge, following indictments against Sal Castro, who was one of the most admirable figures in LA history. It completely tied us up. At the same time it meant that so much of the focus had to be on the police and the courts and the DA’s office so that the real economic elites in this city were hardly ever direct targets of mass action and mass protests.

ML: One of our big organizing goals around No Olympics is to bring into focus all these people behind the scenes, like developers. Leftist history still feels repressed in Los Angeles. It’s not like Berkeley, where they discuss the free speech stuff a lot and at least pretend to celebrate the Black Panthers. In LA, they really don’t want to talk about it at all. And it’s amazing to me that history sort of repeated itself anyway, even without people knowing about the precursors.

I taught my first teaching job at Evergreen State in Olympia, Washington. Most of my family are in Washington. I used to visit historic battle sites in Washington. And what’s interesting is in Seattle, nobody remembers that it had the most successful daily labor paper in the country. Hardly anybody is conscious of its great general strike. But go 100 miles south to Centralia, Washington, where a Wobbly First World War veteran, Wesley Everest, was tortured and murdered, and you see the biggest American flag I’ve seen anywhere except for some auto dealerships in Southern California. This was the community that killed the Wobblies, and this isn’t still a fraught question there. But go to the town next to it, Chehalis, Washington, which was a union town, railroad town, and there’s still bitter rivalry between Chehalis and Centralia high schools. Chehalis blocked off the railroads for a long time. Railroad workers refused to stop in it. So history still lives there.

I became very interested in this question: Why do some histories become local traditions that persist over generations and other enormous and heroic histories seem to be entirely forgotten? I started the LA project and wrote it with Jon largely because I discovered when I was teaching at UC Riverside, which of course is the only campus that has a student composition that roughly mirrors normal California, how many of my Latino students in particular came from families who had been active in the farmworkers movement, in the Chicano Moratorium, in some aspect of the Chicano movement, in the labor struggles, Justice for Janitors, the hotel worker struggle, and so on. And I realized that there was this successful and very crucial transmission of experiences of struggle and understanding of past struggle. And that convinced me that writing a book about a movement history of the ’60s in LA would have an audience among younger people. Basically, I saw no case for writing a history of the ’60s merely for people my age or just for the general purposes of doing it. It’s the fact that I saw that this connection can be made. In almost every arena, the ’60s movements were defeated and defeated badly, which is why we’re fighting the same issues today. It planted thousands of seeds that have grown over successive generations, producing wonderful young activists in two generations. That was why I conceived the book, because I hoped there were young people who would find it a useful thing.

ML: You really recenter the Black and Chicano activists and the other stories that haven’t been told. Obviously, the Chicano blowouts are more known about here then nationally, but especially the story of how the Black Panthers were brought down by COINTELPRO is really tragic and horrible.

There’s tremendous misunderstanding about the LA Panthers, but it has only really been written about and studied about in town. There is still deep confusion about what happened. To me, one of the most important political results of the Watts uprising, which I characterize as not only inevitable but necessary, was the creation of the Black Congress, in which you had the US Organization of Ron Karenga and the Black Panther Party and a bunch of smaller LA Black power, Black revolutionary groups united. Karenga is usually depicted as a cultural nationalist in the pocket of the elites and working with the FBI. It’s a little more complicated than that.

They were the major group supporting the Black Panther Party and organized the first rallies to free Huey Newton. COINTELPRO, with the LAPD, were targeting not simply the Black Panthers to create a war but to disrupt the unity that existed for three years after the rebellion. And this is an almost forgotten story of the Black Congress and of Black unity in this period. I can think of only one Black scholar who wrote something about the 1963 united civil rights movement in LA, which was the major attempt in Los Angeles to bring the Southern-style nonviolent civil rights movement using the Birmingham, Alabama, model of demanding simultaneous progress in education, housing, employment, and civilian control of the police. And it was a movement really started by LA’s great local chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality, and it ended up a failure. They tried to negotiate with the political and economic elites who made all kinds of promises but of course did absolutely nothing. August ’65 was inevitable. They had mass civil disobedience, civil rights had been beaten down. And it was followed by an incredible statewide white backlash, which led to the repeal of California’s fair housing law in November 1964. All these white voters voted basically for housing segregation.

This is, again, where you can fault those of us who were active in the ’60s and early ’70s for not being more conscious of how rapidly and massively the whitelash was growing in the state and Los Angeles—particularly in an area which had been the crucible of the CIO in Los Angeles, the industrial suburbs in the Alameda corridor where, until the left was purged in the ’40s, there’d been campaigns for desegregation in housing and schools.

When it was purged it remained hardcore labor Democratic until 1964. And then you had the Wallace campaign in California and the Goldwater movement and a whole bunch of racist and reactionary organizations. In my first book, City of Quartz, I make the argument that the homeowners movement in the 1980s had not been really studied. The left has notoriously neglected the middle classes again, that 40 percent of proto-fascists in the United States. But we need to understand the opposite mobilizations or counter-mobilizations in politics occurring. You have to look at what’s happening with racial backlash and the industrial white working class.

JC: Do you think California’s fundamental land-use problems can be solved?

No. I’m an extreme position on this. I don’t believe urban reform is possible until you can control the land market. Urban reform and issues of housing and gentrification will always fail unless you can control and massively intervene in the private land market, in real estate markets. I’m watching a process right now in San Diego. It’s been occurring in LA for 25 years. My wife is a Mexican artist. A lot of her artist friends are moving out of Barrio Logan in downtown San Diego, which has a very heroic history of resistance against redevelopment. People are opening bookshops and coffee places. This would be great except that what they are inadvertently and unconsciously doing is acting as the Marines of redevelopment, making the area popular, bringing people in. Suddenly all the wealthy hipster types are moving in. We’ve seen this in Venice, we’ve seen it in downtown, all across the country.

Even the best-intentioned efforts to make neighborhoods more livable and exciting tend to lead to the displacement of the people who live in those neighborhoods. And that won’t be solved until you deal with private property and land. There is an alternate, radical tradition which I claim some membership in, which is the idea of Henry George and the San Francisco newspapermen and economists who saw that the greatest threat to democracy and equality in California was the monopolization of land. And he followed in the footsteps of classical political economists who saw land rents as a net deduction from the productive economy. Land rents contribute nothing to the production of goods and services for society, but they tie up large parts of the income.

He was talking about rural California and land monopolies. But it of course can be applied and has been applied to urban land markets as well. And when I taught part time at the urban planning department at UCLA and then later at Southern California Institute of Architecture, I saw so many brilliant plans for reform. They were doomed unless you can control land prices and land use. One thing that could be done perhaps without a major intervention is an inventory of unused property, public property, but also private properties that have been abandoned. And you allow additional use for nonprofit purposes, for homeless people, for small ethnic businesses, workplaces, and so on. I advocated this many years ago in the case of LA, and I said this was basically the best thing to be done with the Spring Street and Main Street corridor in downtown LA. Real estate prices were then at rock bottom. And the city was massively using urban renewal to recycle other parts of downtown for the benefit of big banks. The city should’ve just used eminent domain to purchase that and basically set up an urban homestead project combining low-income housing with workshop spaces for small businesses. The city had all the power to do this. This idea, of course, never got off the ground.

But if you look at the history of nonprofit housing across the country, there obviously are successes, but by and large, as long as it’s subordinate to and preyed upon by the private market, it will never succeed in reaching any of its well-intentioned goals. The thing is that in some countries, without ceasing to be capitalist countries, they’ve been able to make large inroads. If you go to London, where I lived for eight years, you will find public housing projects in neighborhoods that have the highest and most astronomical land values in Europe.

In Canada, the majority of cities have green belts that are municipally owned by the city. This prevents sprawl, creates great parks, and helps to regulate private landmarking and encourages rational urbanization. Sprawl in California has been recognized as a disease for generations, yet we’ve done nothing about it, one reason being that land use on the urban periphery in California and other states is controlled by county government.

LA county supervisors represent populations larger than some Republican states. I once did a survey. I looked at a number of years of the LA Times to see how often the Times reported on land-use decisions by the county board of supervisors. And some years, they didn’t report at all. That’s where developers lay siege. And eventually, most of the time, they are successful in winning development rights scenarios. Urban reform that takes the shape of well-meant actions, designs, and projects and does not address property relationships in this city, the role of the government in subsidizing and clearing the way for practical private development—if it doesn’t address that, you’ll never solve the issue. Without that gentrification will always succeed. In Barrio Logan, they’re really well-known artists, many of whom are great, radical people. But they just pave the way and new landlords will come in

ML: Set the Night on Fire answered a question I’ve long had about why we can’t have bonfires on the beaches at night.

The subversive potential, the utopian potential of the beach has always been something that has received maximum repression against it. I graduated from high school in 1964. And I’ll never forget the summer of 1964—just before everybody got drafted and went off to war. I’m talking about working-class white kids and such. Here’s the beach, here’s the water. There’s a period in New Zealand history when poor whites, mutineers, castaways, and such created a kind of hybrid society with the Maoris, and called it “The Beach.” The potential’s there, and I think every generation of Californians has seen that possibility. And it’s one thing that’s given a kind of peculiar energy to the left in California.

Jonny Coleman is a writer and organizer with NOlympics LA. Molly Lambert is a writer and co-host of the Night Call podcast.