A24

Oh no! There’s a natural disaster/civil war/coup in an unnamed Latin American/African/Asian country. But what’s this? A white American/European is there too?

Thus begins every movie in the genre I’m calling White Person in Foreign Peril. It’s a movie and television motif in which a disaster or conflict of some sort is happening in a foreign country, but instead of telling the story from the perspective of people who are actually from that country, the filmmaker focuses on a visitor to the country, typically a white person. And French director Claire Denis has done it again with her latest film, Stars at Noon.

The film, which won one of the top prizes at the Cannes Film Festival before being released in theaters earlier this month, is based on a 1986 novel of the same name and takes place in present-day Nicaragua, where President Daniel Ortega, who has all but turned into a dictator, has kept the country mired in conflict for over a decade. In the real world, Ortega has overseen a vicious crackdown of dissidents, leading the US Congress to pass a law to monitor corruption and human rights abuses in the country. In Stars at Noon, a young, beautiful journalist from the United States, named Trish, is stranded in the capital after having her passport taken away following her authorship of a few unflattering stories about Ortega’s government. She has turned to prostitution to sustain herself and lives full-time in a motel she refers to as a “cesspool.” Sometimes she can scrape together enough money to make a phone call to an editor she used to work with to pitch a story he doesn’t want.

Nicaragua is a country that’s no stranger to colonialism, imperialism, and more specifically, unwanted US intervention. It’s also a place rife with conflict, even to this day, under the presidency of Ortega. Notably, his regime has taken prisoner and then sentenced to jail the father of Riverdale creator, Francisco Aguirre-Sacasa, who was the foreign minister from 1997 to 2002. In the lead up to the most recent election, Ortega jailed or placed under house arrest seven opponents to his election. Protests about changes to the pension system led to the death of dozens of residents in 2018. In 2020, the government passed a law forbidding “traitors” from running for or holding public office. The track record on rights of indigenous people and women is bad too; abortion is banned under all circumstances, even when the pregnant person’s life is in danger.

Some reviewers have said that Claire Denis’ work with this film is an attempt to critique global imperialism. But to me it’s simply another film centering the Western experience. Surely, there are many interesting stories to tell about the lives of people in a country in such turmoil. Instead, the film spends all its time on a love story between Trish (Margaret Qualley) and an English “businessman” (Joe Alwyn) who it turns out, is actually there to influence the upcoming election (she loves him anyways).

The movie takes place in the midst of our current pandemic, and most of the background Nicaraguan characters are wearing masks. Though it’s a necessity of the era, it only serves to make the non-white characters even more of a faceless, nameless mass in contrast to the protagonist. No main characters are Nicaraguan, but we do make sure to get the name of a seedy government man who solicits Trish’s services. And there are several patronizing scenes that highlight the power dynamic between the protagonist and everyone else. Trish sees Nicaragua, home for millions, as a place she’s trapped in. She disrespects the natives around her, at one point, lording money over a cab driver, having him wait for her as she drinks with her lover and then flees the Costa Rican police who are after Alwyn’s character. When she gets to the cab driver again, she tells him she’s proud of him for waiting for her and earning his payment, as if he is a child completing a task. Trish also says, sarcastically, that she came to Nicaragua because she wanted to know the “exact dimensions of hell.” That line is a near paraphrase of something that Stars at Noon author Denis Johnson wrote when he described Nicaragua as a kind of “hell.”

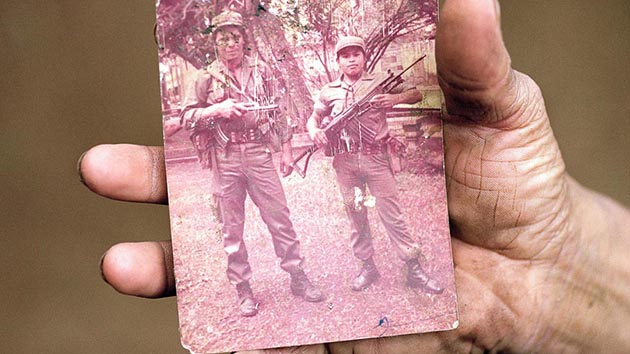

When you watch a movie like Stars at Noon and the American is trying to escape, you’re expected to care about their story and only theirs. No need to wonder what happens to the nameless, faceless people left behind in the only country they know as home. It reminds me of a time that a college journalism professor told me, upon finding out that I have Nicaraguan heritage, that he had really wanted to go there as a young reporter to cover the civil war. Americans, in real life and in movies, go to the country my mother left like it is a fun challenge, a marathon of reporting to prove your worth, whereas it is a place that will never look the same to my family. Overall, the movie’s effect is the dehumanization of foreigners and people who look like foreigners, even if they are from America.

“It really engenders the idea that you can only feel empathy when a white person is involved,” Ali Olomi, an assistant professor of history at Loyola Marymount University, says. “When it’s happening to other people, it is a tragic event to the faceless other. But in order to make it ‘human’, you have to interject a white face, a Western face.”

In fact, Stars at Noon is not Claire Denis’ first foray into the White Person in Foreign Peril genre. In her 2009 film, White Material, Isabelle Huppert plays a French woman defending her coffee plantation amidst a racial conflict in an unnamed African state. By the end of the movie, almost everyone the main character knows has died, from the people in the pharmacy to the men who helped on her coffee plantation. We are meant to feel pity for the woman who has lost her friends, not the actual dead people who are natives of the country and had no character development whatsoever. The people at the heart of the conflict—the locals—are props for her and the audience’s sadness.

The lack of specification as to what country the movie takes place in is seen across the genre, but it is perhaps most notable in Owen Wilson’s 2015 dumpster fire of a movie, No Escape. In it, an American family moves to an unnamed Southeast Asian country for work but a coup happens soon after they arrive. They are left trying to flee the country and the mass of frightening brown people who seem to care more about hunting down Americans than completing their revolution.

“Culture is rarely neutral, it often plays a role in empire building,” Olomi said. “And [movies] become important ways by which people interact and understand ‘those people.’ And so these movies are not neutral.”

I was 17 when I watched No Escape, with a group of mostly white friends, and my reaction was visceral and physical. The movie is disturbing on multiple levels. First, there’s the actual violent content, which includes a graphic sexual assault scene. Then there’s the realization that this is how Western cinema sees you—an other to be fought and defeated. Less than human, something like a beast.

Tequoia Urbina, a screenwriter and filmmaker from Atlanta, feels the trope goes back to the Western savior complex, an ideology in which a white person attempts to help a person of color with the underlying belief that they know best. Urbina also mentioned that a lot of disaster movies fall into this category too, such as 2012, a movie about the end of the world, where massive earthquakes strike every continent, leading the sea level to rise to the top of Mount Everest. The global elite and our American main character are racing to get to China, where huge boats are waiting to give them refuge while they wait for the water level to go down. However, the Indian astrophysicist who initially warned about the disaster receives an unceremonious death because no one bothered to come for him.

The majority of these movies, says Urbina, “have a universal context where this major catastrophe is going to affect the world. But it’s the Americans that “are the ones that can save the world. The Americans are the ones that are directly affected, and everyone else is just along for the ride.”

Urbina can only think of one exception to this trope—Hotel Mumbai. The film is about the real life attacks at the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel in India. While there is an American (played by Armie Hammer), the movie centers on a waiter named Arjun, played by the incomparable Dev Patel, who is actually of Indian descent. Let’s add to that list Hotel Rwanda, a gut-wrenching depiction of a true story, in which a hotelier (Don Cheadle) saves the lives of over a thousand refugees during the Rwandan Genocide.

Movies like these give us an insight into what media could look like if we focused on the people at the heart of a conflict rather than bringing in an American to headline the story. What great art could we produce if we expanded the lens through which we view the world?

Correction, November 2: An earlier version of this story misstated the university where Ali Olomi works.