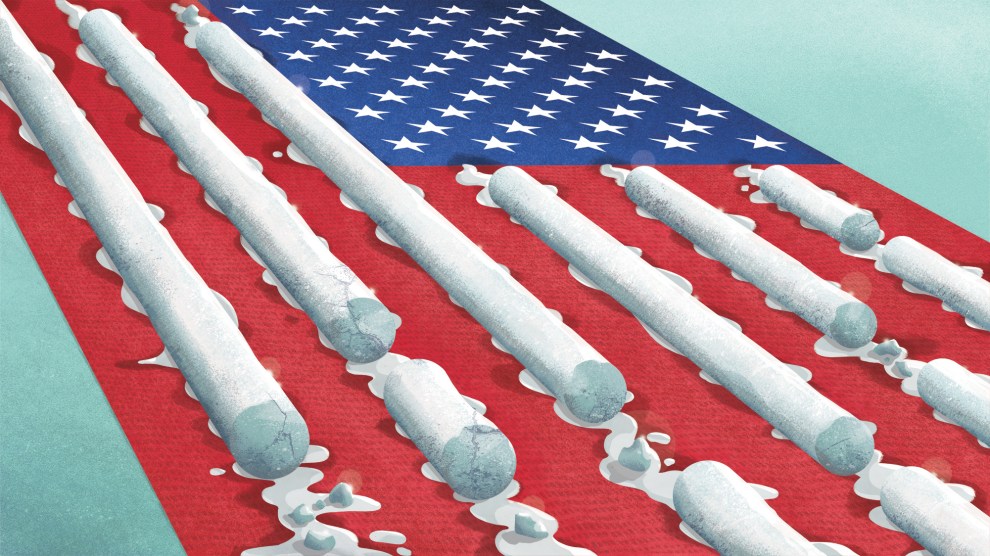

Mother Jones illustration; Nickelodeon; Getty

There’s a party going on on Sesame Street. A diverse group of young children is dancing. One muppet is juggling bowling pins. Another announces that there is about to be some live music. Enter three police officers in uniform singing the lyrics, “If you find yourself out in the cold and you don’t have a hand to hold, well then you might be lost, it’s true. But don’t be scared, here’s what to do: Don’t you fret or fuss, look for one of us!”

The scene, which aired in 1985, is a nice idea, but in reality, the relationship between kids and cops isn’t always so sweet. There are more than 10,000 officers in schools, who are meant to protect kids, yet 20 percent of them say they don’t have sufficient training to do that work. Every day, nearly 2,000 children are arrested. Between 2015 and 2021, law enforcement fatally shot 112 minors. Police violence is particularly real for children of color, who are nearly twice as likely to be arrested as white kids. In 2020, two-thirds of those in the juvenile justice system were children of color, and Black children were six times as likely to be killed by police than their white counterparts.

Yet you’d never think any of that is possible watching the episode of Sesame Street. It’s a classic case of copaganda, a word that became part of our mainstream lexicon around the time that the killing of George Floyd sparked a national reckoning of policing in America. In the weeks after Floyd’s death, showrunners and critics reflected on how the glorification of cops on television shows gives viewers incorrect ideas of the police’s benevolence. As Carol Stabile, a dean at the University of Oregon, told me: “The stories that get told about police are used to promote specific views of policing in this country.”

And some changes did happen. Warren Leight, then show runner for Law and Order: SVU, spoke on a podcast about how he wanted to do an episode portraying what happened to Floyd and said changes would start taking place on shows after what was hopefully an “inflection point.” Brooklyn Nine-Nine, a comedy, was also criticized, and in their final season, those involved with production made efforts to include storylines about how bad some police were and to hold main characters accountable for their actions.

Yet little attention has been paid to how law enforcement storylines show up in children’s media, despite the fact that kids are especially impressionable. “For many children, TV plays a large role in shaping their consciousness and relationship to the world around them,” says Kelle Rozell, chief marketing and storytelling officer at Color Of Change. This makes it all the more crucial that the messages children receive during these formative developmental years combat copaganda and instead reflect important truths about the system.”

In the most popular children’s television shows, I struggled to find a depiction of policing that was anything less than flattering. The closest I came was SpongeBob Squarepants, but even that was basically benign. Though the police officers in the show at times present an obstacle to the titular character, ultimately, they are portrayed as trying to get their jobs done. On the other end of the spectrum is the show most people already associate with copaganda: Paw Patrol, a program about a young boy and a group of dogs that work to protect their community. One dog is a pilot, another is a firefighter. A third is a cop, who helps solve problems around town. It is such blatant copaganda, it’s almost laughable.

There’s also the popular Peppa Pig, a long-running show about Peppa, her pig brother George, and the other animal families in the town. In one episode, two officers visit the titular character’s classroom. One kid shouts “Hooray! The Police!” as they arrive. In the rest of the scene, the officers teach the class of children how to ride their bikes. It’s the kind of utopian policing that imagines cops as helpful adults in a community. In the cartoon world of Peppa Pig, police are your friends. Of course, that is far from the lesson many parents of color want to instill in their children. Many Black parents give their kids, particularly their sons, “the talk,” a warning about how they will be viewed by police and how to stay safe. Parents of Black and brown kids are teaching their kids that the police are not always safe, while the messaging on shows like Sesame Street works to teach the exact opposite, an unrealistic view that police are there to help you find your way.

“In children’s shows, copaganda often shows up in the form of a teaching moment or lesson to encourage children to follow rules. Police are often there to impart a sense of accountability for, and even fear of, making bad choices,” says Rozell. But kids take these inaccurate views about police being universally helpful and consistently good figures with them into the real world as they grow up and become adults.

The show that first got me interested in kid copaganda is Avatar the Last Airbender. It is an animated series about Avatar Aang and his friends attempting to take down the colonizing forces of the fire nation. In this show, the world is divided into four regions, which each correspond to their inhabitants’ ability to control one of the elements: water, air, earth, and fire. Aang is a leader because he is the Avatar, the one person who can control all four elements and ostensibly bring peace to the conflict-ridden world. It’s an incredibly unique children’s television show, in that all the characters are people of color. And though there are local police officer–types, there isn’t a police force at all akin to what we see in real life. At least that was true until the spinoff comic books and sequel series, the Legend of Korra, came out.

In the comics, which take place between the two series, Aang is traveling to rebuild the postwar world. During a meeting about a city that’s being established, Aang says, “What I think this city needs is a real police force. Something to serve its citizens and establish true law and order.” It’s the complete opposite of the tone of the original series.

In the original series, a young girl named Toph develops the ability to bend metal as part of her escape from her kidnappers. By the time the second series rolls around, metalbending is almost exclusively used by a police force that Toph founded as an adult. The leap in character development doesn’t make sense. In the first series, the characters were constantly evading the military and figures of authority because they were being hunted by the fire nation and those loyal to it. Policing was contradictory to the mission of the main character, and there was even an extended plot line about the corruption of one of the law enforcement–type groups. By the second show, the main characters are part of the establishment. They have become law enforcement.

I can vividly remember waiting for the series finale of Avatar the Last Airbender when I was ten. It’s a show I’ve rewatched over and over, feeling that same excitement I did when I first watched Aang defeat his nemesis, the firelord. And little did I know, the show was impacting me. It helped teach me everything from how to be accepting of people different than me to huge concepts like colonization. By the time the Legend of Korra came out, I was a bit older and not as porous to what I was receiving on television. Even so, it took me until I was in my early 20s to realize that the message they were feeding viewers was yet another version of copaganda. As I watch clips of Peppa Pig, whose Instagram has close to half a million followers, praise the police officers she meets, I wonder what effect it will have on the kids watching it now. How long will it take, if ever, for them to realize that they’re being fed a message that’s not entirely accurate?

I asked Rozell how to incorporate more nuanced portrayals of policing in media for kids. “It is critical that [media] leaders focus on who is on screen and who is in charge of the story,” writes Rozell. “One way to do this is by inviting more people with expertise and real-life experience into the writers’ room to advise on these critical issues, share stories and collaborate on storylines. This hard look at copaganda in children’s shows is long overdue.”