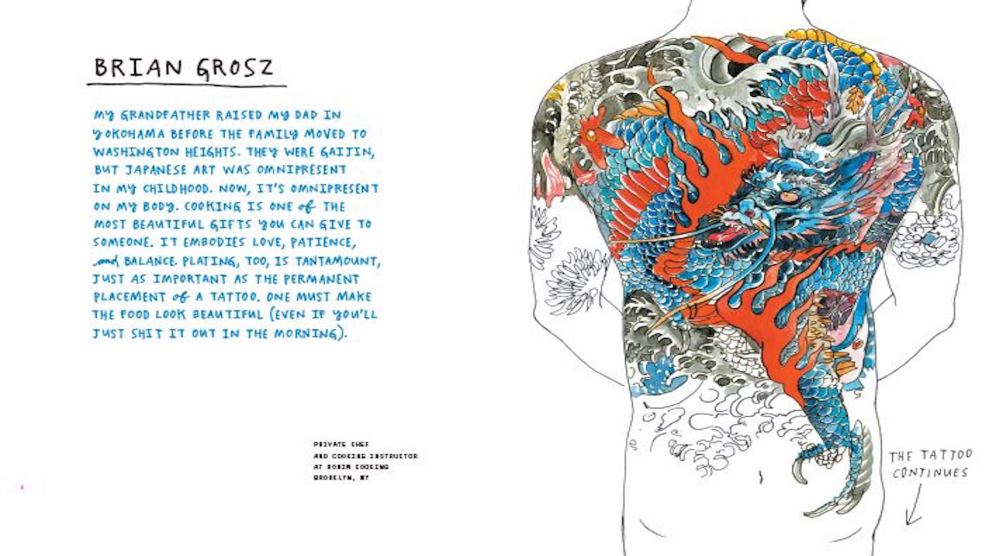

It is fitting that I interview illustrator and designer George McCalman on All Saints’ Day. When I flip through his new book, Illustrated Black History: Honoring the Iconic and Unseen, I cannot help but think of the children’s hagiographies of my youth. But rather than Joan of Arc in her armor or Sebastian’s arrow-pierced torso, I see James Hemings in a tall white chef’s hat, with Mona Lisa eyes that follow me as I study the page; and Sister Rosetta Sharpe with her guitar, surrounded by pulsating rainbow soundw aves that threaten to make me dizzy. McCalman’s book is the carving on the cathedral wall, and I am the peasant hungry for a world of knowledge I am embarrassed to know too little about.

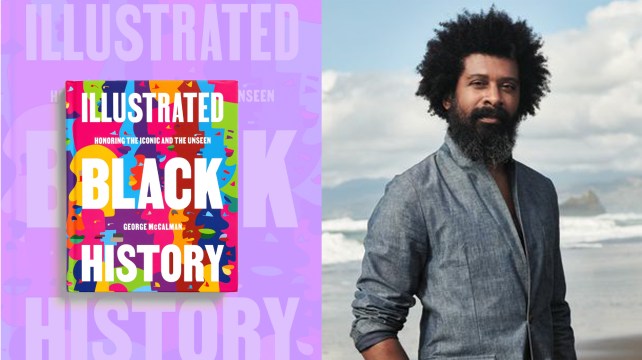

As the title suggests, that’s partially the point. “There are still not a lot of books that are accessible about Black history,” McCalman tells me over Zoom. The book contains 147 portraits of Black luminaries, hand-illustrated by McCalman and accompanied by his biographies of their lives. It feels partly graphic novel, partly anthology, and even partly magazine—indeed, McCalman spent years working in magazines as an art director, including at Mother Jones. I know for sure he will resist my attempts to classify Illustrated Black History as a hagiography. “All saints are sinners and all sinners are saints,” he reminds me with a laugh. “This book is still an anomaly. I’m here to say, ‘No, this is who you should be paying attention to. This is who every American should be paying attention to.'”

McCalman started the project simply enough. “I had assigned lots of art to many artists over the years, and I knew people worked well within parameters,” he writes in the book’s introduction. “I decided I was going to research, write, and paint one pioneer a day.” For each day of February 2016, he would sketch a portrait in black and white, so as not to be distracted by color. That series eventually bloomed into this book.

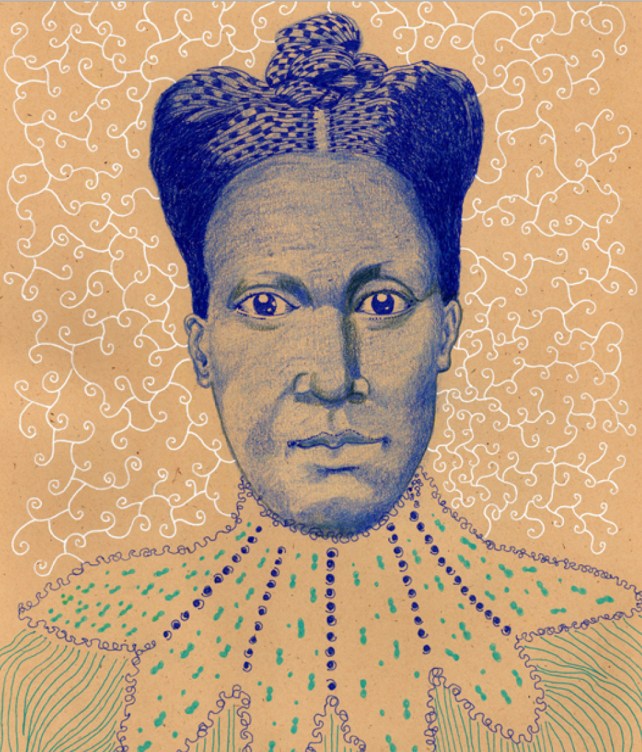

Illustrator and author George McCalman

Only a few of the figures depicted are members of the “traditional Black canon.” That’s partly, McCalman admits, because he studied the people that spoke to or “found” him, people that came up in internet searches. It’s also because McCalman, as an immigrant to the United States, was always “outside” Black American history and all US history. “It always incensed me that the Black community wasn’t seen as part of American history, not in a meaningful way,” he says. “That’s what America was: separate. Two halves of a whole.” Now, McCalman’s book serves as just a few stitches in the mending. Here’s more of our conversation, condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

Was there a specific moment or event, in history or in your life, that made you say, “Now is the time to make this?”

It’s less tied to external metrics and more like an internal calling. I was really just curious. I’m a contemporary child of the world. So I read, I know what’s going on at all times. I’m an avid news consumer.

I also knew. culturally. that this country is still very far away from reconciling its own history. And that that is an important thing for this country—to basically reclaim its existence and to make peace with itself. I think that is why this country is so fraught right now: we have not made our peace with our history.

There still are not a lot of books that are accessible about Black history; it is still a subject that is either dismissed, discarded, or attacked. And all of those things together don’t make for a smooth process, even internally. I had to deal with a lot of obstacles in making the book represent the purity of my original idea.

What obstacles?

One of the largest challenges I faced was the cultural ignorance that there is still in the publishing industry. It tends to be kind of polar—it’s not as complicated and complex and interesting as we are as people.

It’s either that people are falling over themselves to apologize, or people are just outright hostile to the idea of it existing the way that I wanted it to. We all know the metrics of producing a book, a magazine, a journal, an online magazine, whatever it is; oftentimes, the stories tend to be reduced to their components.

As the person who was writing it, who was doing the art, was designing the book, I was continuously reminding the people that I worked with that they were creating a cultural offering, not just a book.

Nina Simone, singer and songwriter: “I tell you what freedom is to me: no fear.”

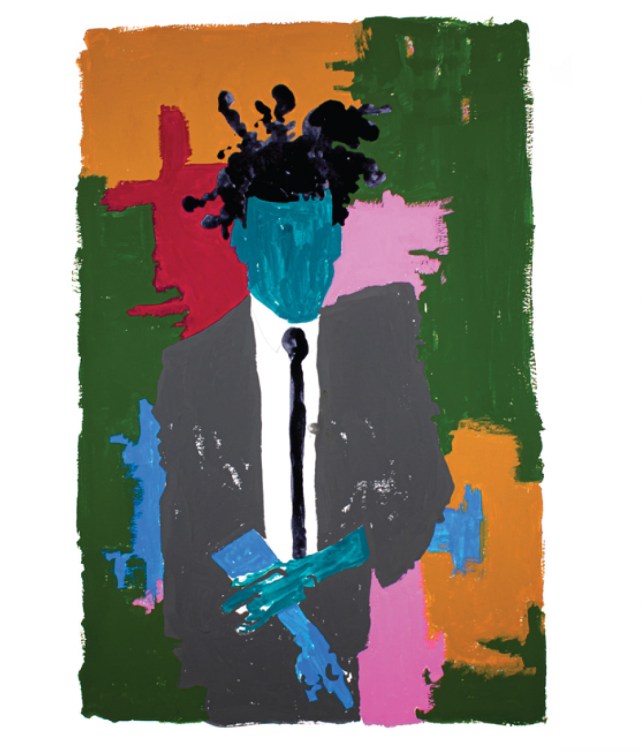

Jean-Michel Basquiat, artist: “I don’t listen to what art critics say. I don’t know anybody who needs a critic to find out what art is.”

Who was your first portrait of? Was there a reason you picked them?

The original portrait series I did six years ago, and the very first person I painted and illustrated was Edna Lewis. I have several friends who are food writers who had introduced me to her. And as a person who knew a lot of Black icons growing up in New York, she was one of the people that I actually didn’t know that much about. I realized a lot of people don’t know a lot about her, and how important she is to culinary history in general, as an archivist, as a cook, as a writer, and as a librarian of Black culinary history, that I just felt that she needed to be known a little bit more.

I remember sitting and painting her and just feeling like I was actually getting to know her through the process of making the portraits. And that’s a really powerful thing to feel. And it’s something that I actually carried with me through the entirety of making this project. I felt like I was getting to know the essence of all of the people, even the controversial ones, that I was creating portraits of for this book.

Jackie Joyner-Kersee, track-and-field athlete: “Those who know why will always beat those who know how.”

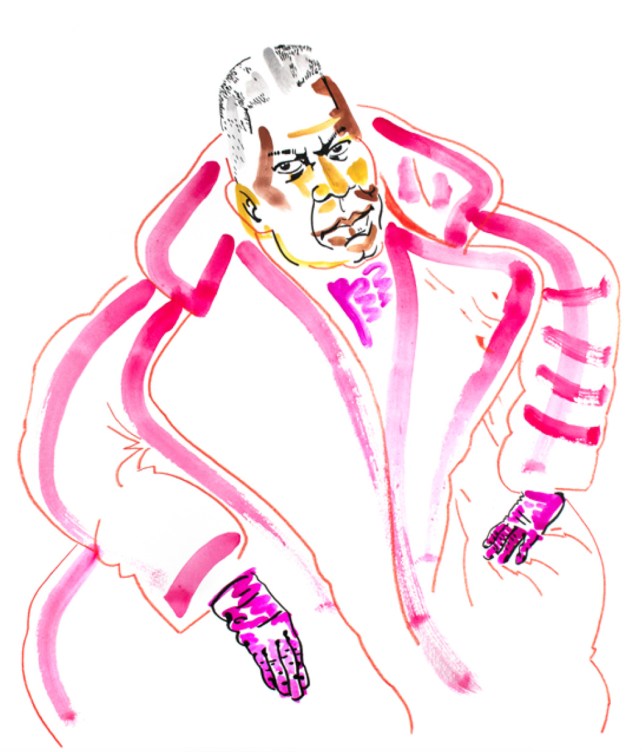

André Leon Talley, former Vogue editor: “Wearing clothes should be a personal narrative of emotion. I always respond to fashion in an emotional way.”

It struck me as being different from other books in that, I think, you can feel that nuance in some of the stories that you tell, and the way you’ve decided to tell them. Ben Carson is probably going to be the example where most people are like, “Why is this guy in here?” And I think you handle that by talking about his complicated legacy. The same with Richard Pryor. You try to hold a bit of balance between the not-great things in his personal life while giving him credit as an artist. I think you can make the case that all of these people are heroes, but they’re complicated.

They’re all presented as complicated people. That is how we actually make our peace with history. We tend to in America either demonize or deify people. And it is a very uniquely American thing that we still have this issue with the binary, and the polarity of how we talk about political and cultural things.

Ben Carson was one of the people that I was like, I’m not sure what I have to say about him, because he’s in this book for a really important reason. I’m basically representing the complexity of our icons who fall from grace. And in the Black community, it is actually a more complicated thing, because growing up, we had so few of them compared to [white people] and they were always judged more harshly or more definitively. It wasn’t that all of our icons were the same. We knew that our Black icons were perceived differently than our white icons.

What Ben Carson represented was medical brilliance. He wasn’t a celebrity, but he was someone who was actually saving human beings’ lives. And then to have him come out years later as a Republican and have his star fall so precipitously—he went from being seen as a genius to being seen as frankly a doofus, and just not that smart. I really feel for him, not that he needs my sympathy. But to go from one extreme to another when he’s still a person—he’s still a human being, he still is a complicated person.

Guion Stewart Bluford, engineer and astronaut: “I’m an engineer, and I’m Black and I’m lonely out there.”

Fanny Jackson Coppin, educator: “Good manners will often take people where neither money nor education will take them.”

There are so many different styles in here, which is so fun. Some of them make sense—like Basquiat, because it’s done in his style—but others run a whole range.

Every one I started from scratch, and I wanted them to be as individual as the people. [Otherwise] it would have been harder for me to make this claim of them as complex human beings. If I had rendered them in all the same styles, it would have totally undercut what I thought was an essential part of making this about Black history.

You’ve talked about viewing American and Black American history from the perspective of a “voyeur,” because you’re an immigrant. Can you talk about that? Has this project changed that?

I love saying that I’m an immigrant, because I am proud of the fact that I’m an American citizen who also has an outside perspective. It has made me a better human being, thinking about things both inside and outside of being a member of this American society. I don’t feel weird about representing that; I think of it as a superpower. That it is how all Americans should be thinking about things. It’s not us versus them. It’s us and them.

We’re in a political climate where history curricula are under attack in parts of the country, especially because of their focus on Black history. Do you see your book as part of a resistance to that trend?

This book shouldn’t be revolutionary, but it is. This book shouldn’t be political. But it is. It should just be about Americans, but it’s not. There’s a lot that I wish this were, but I also live in the real world. I know that this book is going to be targeted, that it’s going to trigger some people who think that it is what it’s not.

What it is to me, I’ll tell you, is an offering. That is how I think of it. First and foremost, it is a cultural offering about an issue and a subject and a people who have been ignored.

When I think of illustrated books, I think, probably incorrectly, of children’s books. This is not juvenile. Who is this book for? Who do you hope reads it? Is it for primarily Black Americans, white Americans, non-Americans?

It is primarily for the Black community to see ourselves. But I also made it accessible deliberately, so that anyone could pick it up. And too often, race is reduced to Black people and white people. There are a lot of other people living in this country. I would also offer that this is their history, too. If you’re an American, this book is about you.