Mother Jones; Getty; Unsplash; Wikimedia

From February to April, four men were found dead in Lady Bird Lake in Austin, Texas. The Austin Police Department said these were all accidental drownings, caused by a combination of alcohol and easy access to the lake, which can be challenging to see at night.

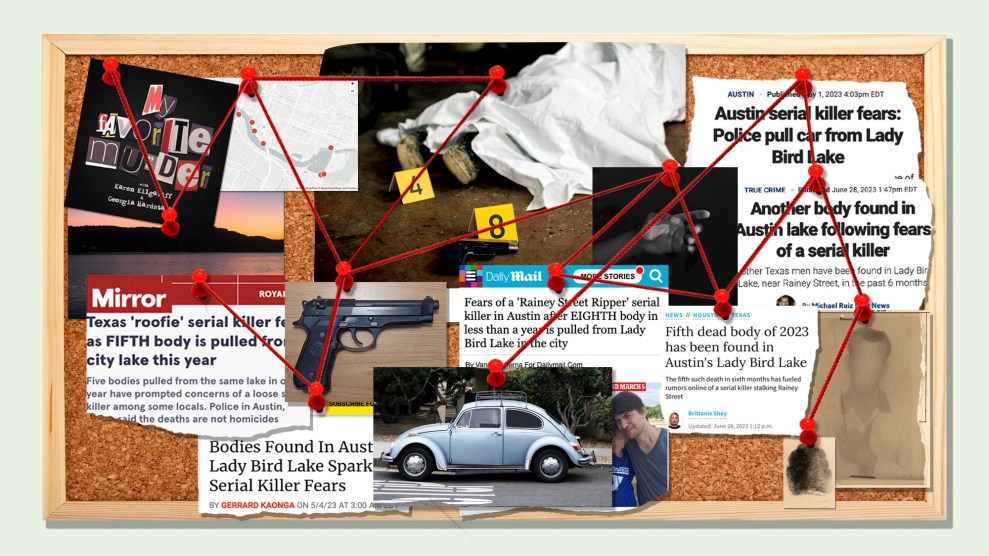

At the time, I’d heard faint rumors of a shadowy figure stalking the city’s vibrant streets. According to numerous online sleuths filling up my social media feeds, the “Rainey St. Ripper” preyed on drunk men parading around one of the city’s popular bar areas near downtown. One of the most vibrant online forums for this chatter was a Facebook group called “Lady Bird Lake Serial Killer/Rainey St Killer,” which exploded to nearly 100,000 since its creation in February. The group quickly became a hub for speculation and theories, with some members suggesting that APD and the Travis County Medical Examiner were involved in a conspiracy to cover up the murders. Meanwhile, on Tiktok, the hashtag #RaineyStreetRipper amassed more than 1.2 million views, with the vast majority of videos detailing various rumors and hypotheses surrounding the case.

There has always been a certain appeal to true crime in America, but now we’re watching more true crime than ever. Not only consuming it, it turns out—internet sleuths searching and gossiping about a ghost killer in Austin is the latest in a series of internet-fueled crime dramas that have played out across the country. Just recently for The Atlantic, McKay Coppins covered the town of Moscow, Idaho, a community left in paranoia and fear after social media detectives flocked to the area to “help” search for a killer (spoiler alert: It made things worse). Web sleuthing, in general, has been on the rise since the Boston Marathon bombing in 2013, and in turn, has evolved into one of the more problematic forms of citizen journalism.

Despite these broader trends, true crime never really appealed to me. But that changed when, just as social media was starting to churn with rumors of the Rainey St. Ripper, an Austin man named Raul Meza Jr. turned himself in for a series of unrelated murders that began more than 40 years ago. He was declared the city’s first “serial killer” in 138 years, and he had nothing to do with the men who turned up in Lady Bird Lake. Perhaps against my better judgment, my distaste turned into genuine interest.

After all, I thought, shouldn’t I be at least a little curious, as an Austin resident, to understand why some folks are so adamant there’s a killer on the loose? Turns out I’d been crime-pilled.

When I reached out to journalist Rachel Monroe, author of the 2019 true-crime book Savage Appetites, she told me that internet sleuthing is both human nature and a little bit of ego. “It’s flattering to think that you’re going to be the one that comes up with the answer that no one else did,” Monroe said over email. “The internet adds another element, too—social media makes it collaborative (or, sometimes, competitive), and algorithms incentivize the most sensational theories.”

Not long after I started paying closer attention to the whispers online, the 100,000-strong Facebook group community that started everything was shut down. But the two new spaces that followed in its wake—the private “Lady Bird Serial Killer” community and the public “Lady Bird Lake Mysterious Deaths-Does Rainey St Have a Serial Killer?” with 300 and 3,100 members, respectively—didn’t lack for wild theories of their own.

It was enough to make even the most tweaked-out yarn waller blush. Speculation ranged from spiked drinks, gang activity, and rehashings of a decades-old theory that the drownings were connected to other deaths across the United States. It’s reminiscent of a work of fiction, so much so that Monroe believes that a “certain segment of the population has become crime-pilled.”

“People expect the world to play out like an episode of Criminal Minds,” Monroe said. “Accidents start to look like crimes, and of course, every crime must be part of some bigger story arc—a cover-up, ideally, a serial killer cover-up.”

I felt that, and at some point, I started having a sort of grim fun with it all. If you can ignore the casual homophobia and racism (there were multiple theories alleging these men were in the closet, as well as dog whistles suggesting these deaths were the result of “defunding the police”), there’s a macabre enjoyment that comes with baselessly speculating about murder. (There’s a reason My Favorite Murder is one of the highest-earning podcasts in the world.)

That said, it was rotting my brain. Most of the “evidence” I was reading about was anecdotal at best, but the more I dug into the various theories, the more paranoid I became about my surroundings. Any crime in the city was evidence of the Ripper. “If we don’t impose a pattern on the chaos,” Monroe said, “it just feels like overwhelming chaos.”

Things then got very sad very fast. Never a member myself, I lurked in their forum every day for a month. I was fixated—desperate for a new development, a new theory, or perhaps, even a new body found in the lake. I would scroll further and further down the page reading every post and comment, and for small, fleeting moments a little bit of humanity would hit me.

“Hi, I joined this group because my brother was a victim…”

“Hello, my mom was a victim a few years ago and I can’t help but think she’s related to this…”

These were real people who’d had their family members taken away from them in absolutely horrible circumstances. And for me at least, seeing these pleas for help—between very serious conversations about whether these men were gay and if the city of Austin was being corrupted by the “Soros agenda”—ruined any amount of interest I still had in the case, and in true crime as a whole. None of this was helping anybody.

APD’s lackluster response, as well as its general history of misconduct and incompetence, was part of the reason why folks thought there could be a serial killer in the first place. When I reached out by email with questions to APD, the department sent its initial press release from April, stating that the area will “see increased safety measures in the popular entertainment district” along with a message that they “do not have someone available for an interview about this topic.”

It wasn’t long after APD got back to me that another unidentified man was found in the lake. The popularity of the Facebook groups soared, with almost 900 new members joining the two communities by the end of June. But for me, the crime pill finally had worn off. I unsubscribed from the groups. The echo chamber of wild hypotheses, meanwhile, grows louder and more convoluted by the day.