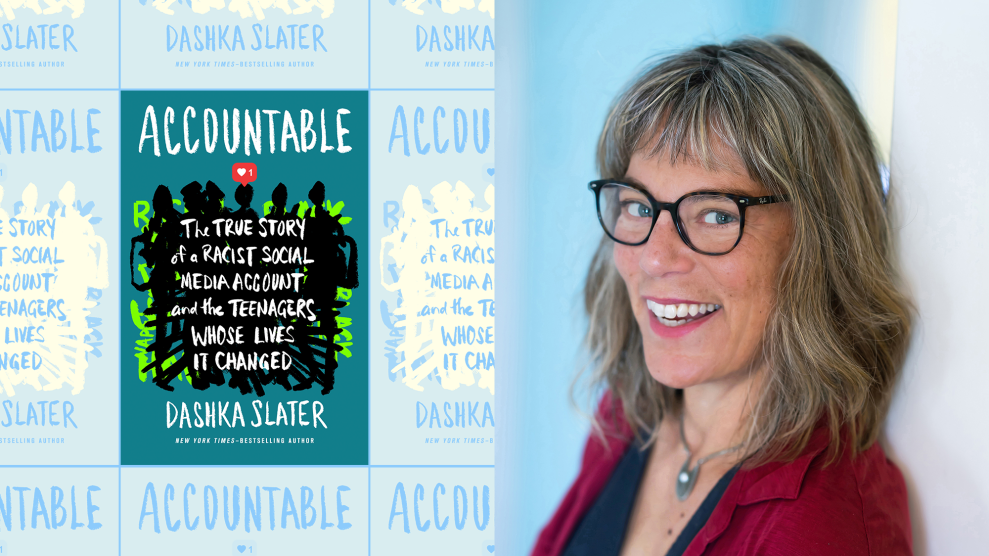

Author Dashka SlaterMother Jones Illustration; photo by Amy Sullivan

First things first. Unlike, say, certain Supreme Court justices, I’m willing to disclose my conflicts of interest. I’ve been friendly with journalist Dashka Slater since we were both young reporters doing features for the alt-weekly East Bay Express. Over the years, I’ve commissioned her to write several articles and essays for Mother Jones. She interviewed me for one of my book events, and swims regularly with my wife in the San Francisco Bay.

So I’m biased! But I think I can objectively say that Slater, whose books to date are written for young people—sometimes quite young, like her picture-book series about a delightful snail named Escargot—is an exceptionally dogged reporter and talented wordsmith. The kind of writer we magazine editors compete over. The kind who digs deep and thinks deeper.

That was true of her young adult nonfiction best-seller, The 57 Bus, an oft-banned exploration of youth, crime, race, and gender identity that began as a 2015 New York Times Magazine story about some Oakland teenagers who thought it might be humorous to set fire to the clothing of a gender-questioning teen who’d fallen asleep on a city bus. It is certainly true of her new YA book, Accountable: The True Story of a Racist Social Media Account and the Teenagers Whose Lives It Changed, which goes on sale next week and is excerpted in this week’s Times Magazine.

Accountable is built around events that took place beginning in 2017 in the Bay Area town of Albany—events that turned the local public high school and tight-knit community completely upside down. An Albany High boy creates a private Instagram account, which is followed by 13 other kids, and starts posting a series of “edgy” (problematic) items, including racist memes targeting Black female students. Such things never stay private, of course. When the word gets out, chaos ensues—and the responses of parents and administrators only seem to make things worse.

It’s a valuable case study for any community facing this sort of online blowup, which Slater says is “shockingly” common. Her close access to the key players, the fruit of hard work and perseverance, gives readers a nuanced perspective into an incredibly thorny social situation. Written in a style accessible to teens, the tale is harrowing even to adults, and deals deftly with difficult questions about punishment and accountability, and our very human tendency to rush to judgement.

In this interview, edited for length and clarity, Slater and I delve into all these dicey topics, but I figured I’d start out easy.

Instead of telling the story straight, you intersperse it with poems and personal musings and listicles like “The Rules of Instagram circa 2017” and “Some Things That Happen When You’re Black in a Mostly White School.” The chapters seldom exceed a few pages. It’s a light approach to a daunting subject. Will you talk about your style choices?

Yeah. Well, I’m writing for teenagers, so one of the challenges is to try and figure out a way that information that, as you say, is daunting, can be made accessible and digestible. The people that I most want to reach are the people who are the least likely to pick it up. I want to get the apolitical white boy who has never really thought about any of this but is super into online stuff.

Who never reads a book.

Exactly. So if I manage to get that kid to crack the spine, I don’t want to throw up any barriers.

You learned of this Instagram account around the same time the Albany community did. You’d literally just written this other really intense nonfiction book about gender and race and the compulsive cruelty of teenage boys. What went through your head?

My very first thought was, Oooh, that’s interesting. I want to know more. And behind that thought is a whole lot of emotions that I think would cause most people to say, I don’t want to spend years of my life feeling this shock and horror and concern and distress and repulsion and fear. But, being a reporter, those exact same emotions are a siren song.

Sure, but wasn’t some part of you like, “Oh, please, no!”?

That would have been smart! What I actually thought was, This seems right in my wheelhouse. And then, I had no idea that in some ways it would be even more painful than The 57 Bus. That was a couple of years of really worrying about the people involved. And this was, you know, the worrying isn’t over! It’s been almost six years.

Accountable covers some really touchy ground. What were some of the challenges you faced in gaining people’s trust and cooperation?

When I started reporting, 100 percent of the people involved did not want to talk about it. The people who had been targeted by the account were still reeling—they were 16 or 17 years old and really in the throes of depression and anxiety. And their parents were understandably, correctly, protective of their children. That was a firm brick wall.

There was one opening: They said we don’t want to talk about it now. We’re not ready. So the door was left slightly ajar. I eventually had one person, Charles, who wanted to talk. He was the person who had set the account in motion. He’d really kind of already lost everything he had to lose. Then one of the targeted girls said yes. And once I had one on each side, doors started opening. That’s when I knew I had a book.

Some of these posts were really hurtful. They joked about the N-word, the KKK, and nappy hair. One had photoshopped pictures with nooses drawn around the necks of a Black student and a Black coach. Yet many of the kids who interacted with the account, mostly Asian American, didn’t seem to grasp how bad it was. How do you explain that?

It’s really interesting, isn’t it? These were good students who were educated in the Bay Area and had had plenty of lessons about racism and civil rights and slavery. But they hadn’t really connected those lessons, I think, to the lived experiences of people they knew. And even though it was a diverse group of friends, and these boys were friends with Black girls, I don’t think they really investigated what the experience of those girls was.

They just saw them as peers and didn’t really think about it?

Exactly. They kind of felt like, well, we can make these jokes because we have these friends. Without a proper grounding in the empathic experience of people who are unlike them, they could see that kind of humor as harmless.

Or they were too immature to grasp how harmful it was.

Yeah, too immature to think about how it would land—and their life experience was too short to understand that historical things like nooses still have an intense amount of power.

What were the consequences for the targeted girls?

A lot of depression and anxiety. I often thought about it, you know, that the job of every adolescent is to construct what your identity is going to be. These girls are doing that with the added responsibility of basically trying to create a shell around themselves so they won’t be derailed by the ambient racism in our society. And this account broke that whole defense they’d built like an asteroid coming through the roof. Suddenly the things they’d convinced themselves were true—that people are taking you seriously, not judging you for the color of your skin, that you are safe, people aren’t staring at you, aren’t saying things behind your back—all of that just vanished, and they were left really vulnerable.

The irony is that, after the account was exposed, other kids actually were staring at them.

Exactly. It’s cool to be known in high school, as one of the girls says, but not for that.

It’s like when people find out you have cancer and start treating you differently.

Yes. And it’s all mixed in with the usual high-school politics—who’s friends with whom, and some people are friends with some of the boys and some aren’t, and they want to gain some kind of cachet by talking to you [a targeted girl] about it, or feel some way about how you being targeted resulted in their friend getting kicked out of school.

A total shitshow, in other words.

You’re doing a great job of summarizing. Yes, a total shitshow.

I struggled with these next questions, because I didn’t want it to seem like I was defending these boys. I think that underscores a key tension. Namely, we feel empathy not only for the kids targeted—because that was obviously terrible—but also for those responsible, because of the mob mentality that ensues. One can’t help but wonder whether the punishment fits the crime.

What’s interesting in the way you frame the question is there’s an assumption that accountability and punishment are the same—and that the way we respond to someone causing pain is that we need to deliver some amount of pain to them. What’s lost in this equation is, what is our goal? Is it to hurt the person who causes the pain proportionately? Or is it to make sure the people who caused the pain understand what they did, take responsibility, don’t do it again, and work to try and fix the harm that they caused?

Restorative justice, as opposed to punitive.

Right. I would argue that should be our goal, particularly with young people. To get them to really own up. And that’s not easy.

For grownups, let alone teenagers.

Exactly. And we have zero role models. You can’t say, look at X public figure and how they responded when they harmed somebody else.

They hired a PR firm to burnish their image.

Right. We’re all kind of babies when it comes to true accountability. But when you go the punitive route—and in this case they went with a sort of public shaming and shunning, so these kids were ostracized from the entire community—that does not help with accountability. I would argue that shame is the enemy of accountability.

I’ve read some studies on groupthink, and it’s nuts. You can get someone to give an obviously wrong answer—like 2 + 2 = 5 level of wrong—to avoid standing out from their peers. What role do you think groupthink played in this affair?

It was certainly at play with the 14 kids following the account. Teenagers are hypersocial, so what’s true for any adult about groupthink is more true for them. There were varying levels of awareness that this was not cool, and a pretty high number of kids who thought, I don’t really love this kind of joking around or this seems like it crosses the line or I’m actually friends with these girls—little alarm bells went off. But to a person they decided, I’m not going to say that, because then I would be on the outs.

And we’re thinking: Why didn’t you just say something? But Dashka, as parents, we both know that teenage boys make the most idiotic choices and then seem incapable of explaining why.

Yeah. You say, “What were you thinking?” And your kid goes, “I wasn’t really thinking anything.” But that is exactly what is happening in their brain, because under what’s called “hot cognition”—when they’re with their peers, emotionally activated—the cerebral cortex, the center of reason and logic, is pretty much bypassed. They’re just going with the amygdala, which is the center for emotions.

Also, they don’t want to be the nail that gets pounded down.

That was a big part of it. This group was very hierarchical, and there was a lot of in-group bullying—sort of play-hitting that hurt. In the internal jockeying for position, they didn’t want to be sent to the bottom rung.

These boys had varying levels of culpability—some didn’t interact with the account at all after following it. So when is it fair to brand an immature kid as a racist?

In general, branding people with any label is not respecting our human dignity and capacity for transformation and growth. I think it’s perfectly legitimate to label behavior as bad, and these kids absolutely behaved badly. But as adults, we know that the person we were at 15 or 16 is not the person we are now. With the intervention of adults who can help you learn from your mistakes, we don’t have to be calcified at our most ridiculous and stupid and harmful.

Weren’t at least some of the targeted kids more willing to forgive than their parents were?

Yes, for some, living in the harm felt counterproductive. For at least one of the targeted girls, forgiveness was the way out—she didn’t want to live with the poison anymore. She’s a particularly empathic person. Which is not to say that she wasn’t outraged about having been targeted, and about all the ways in which the boys had behaved terribly and not taken responsibility. Because those things can exist at the same time. But the parents were just in full, protect-my-kid mode. When you feel like somebody is causing pain to your child, it’s pretty hard to see anything else.

In Albany, everybody was under stress, and everything was moving so fast, and the whole community is in an uproar and demanding results right away—and school administrators are trying to figure out how to deal with this demand for retribution and a community in pain. And then parents are lawyering up and kids can’t concentrate in class and the teachers are upset and wanting to know what’s going on. The whole student body is off kilter. In that environment, nobody really has the space to think, Okay, what are the nuances?

You describe an attempt at mediation by the school that went very wrong. The coordinators completely lost control of the situation.

It was the perfect example of what I just talked about. With everybody in crisis mode, they grasped at, like, maybe we can do a mediation? We can package it up and put it away and go on with the rest of the spring semester. And that really did not happen. The girls who had been targeted and the kids who’d followed the account all walked out of there more traumatized than when they walked in.

And the other students were holding a sit-in outside, basically chanting that these boys were racists.

It’s the stuff of teenage nightmares. Not all of them were chanting. There was actually a lot of silent staring, which is also the stuff of teenage nightmares. You’re standing in front of a couple hundred of your peers and they’re either yelling that you’re a racist or staring at you and not speaking.

Oh, boy. So, when you sent advance copies of the book to your sources, what feedback did you get?

I can’t emphasize enough how traumatized people in this community are. Some of them have just been, like, I tried to read it, and I started having nightmares or I couldn’t stop crying. The feedback I particularly appreciate comes from the people who say, like, I didn’t know. Because there were roughly two sides, but on each side there were many variations of people and different groups of people. I’ve had a lot of people tell me how eye-opening it was to get the full story.

You think your book will help other communities navigate a fiasco like this?

That is my overarching goal, because this happens so frequently. I get a Google alert every time there’s an incident like this, and I get them every day. So I want to give school communities the tools to understand what the phenomenon is, and that it is a phenomenon and not just a terrible thing that was done by these terrible kids in their terrible community—which is how it often gets framed. This can happen anywhere, and does. At the same time it was happening in Albany, it was also happening in Berkeley, almost the exact same scenario.

Has the community gotten past this by now, or is it still hanging over Albany High?

Most of the families who were directly involved have left the school system, but not all. There’s been a lot of turnover, but many of the same teachers are still there. And so there is a kind of undigested quality to it. For the people involved I would say it is very much alive. For my piece in the New York Times Magazine, I had to do a new set of interviews, and I have yet to do interview somebody who isn’t emotional. The fact that people are still crying in interviews says to me that it is very much still a raw topic.

People including the perpetrators?

Yeah.

You wrote in a Mother Jones essay that you think Accountable, like The 57 Bus, may get banned in lots of places.

That is certainly my fear. There’s no exploration of sexuality in this one, but I do talk about, you know, the history of lynching and the various ways that racism impacts people’s mental and physical health. So that might be too “woke.”

You also show how racism is woven into the threads of our society.

Yes, and that there are overtly racist groups pumping out online memes meant to be attractive to young people, particularly young men.

Yeah, that was another cautionary tale, the way internet culture normalizes this stuff such that a lot of young men are able to dismiss it as just horsing around.

It’s also a big part of boy culture to want to cross the line—to touch the electric fence. And it’s nicely packaged. This transgressive behavior has been kind of commodified so that boys can disseminate it and try to imitate it.

Is there anything I missed—anything you would ask yourself?

[Laughs.] I don’t think so. I will say that this whole dilemma of, I don’t want to seem like I’m making excuses for the boys is a huge part of this book and the questions I get asked about it. It speaks to the difficulty of the whole topic that we all worry about perpetuating the system of white supremacy and injustice that allows white men and boys in particular—although these were mostly Asian boys—to get away with stuff. But it’s also important to remember that no young person invented this system, and that these kids are young and vulnerable—and human. We only perpetuate the system when we fail to realize that.