Mother Jones illustration, Brian Treitler

As an elder member of Gen Z, I grew up on the internet, my platform of choice being YouTube: Videos about Avatar: The Last Airbender as a kid, then questionable conspiracy content by the platform’s early viral creator Shane Dawson and quirky BuzzFeed shorts in high school. But at the age of seven, when YouTube launched, I didn’t understand how the internet worked.

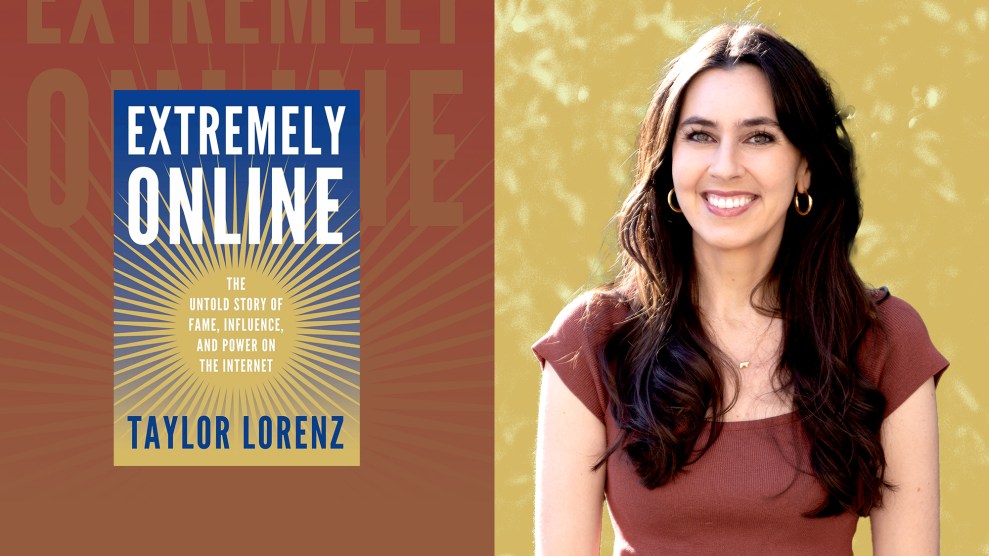

Many early viral stars didn’t, either. Being an influencer can be profitable, but it’s a rather new career path. In her debut book, Extremely Online, Washington Post columnist and tech writer Taylor Lorenz traces the rise of the internet influencer, the social media apps behind them, and the users who can’t help but stay glued to the antics of the Jake Pauls of the world.

For over a decade, Lorenz has been reporting on online culture, influencers and technology at outlets including the New York Times, the Atlantic and the Daily Beast. In April 2022, for the Post, she revealed the user behind Libs of TikTok, a popular account that attacks LGBTQ+ people and promotes homophobic and transphobic rhetoric—and has a counterpart on X, formerly Twitter, which suspended Lorenz shortly after coming under Elon Musk’s reins.

Lorenz wrote Extremely Online, she told me, because so many books on social media apps just focus on founders and investors; she wanted to write a social history including influencers and everyday users too. Being extremely online is a culture unto itself. It’s a world we look at “through the lens of these corporate narratives and specific platforms,“ Lorenz said, “but we don’t really zoom out and kind of take stock of this whole industry that’s arisen.”

As a journalist, I find whatever is happening to Twitter hard to watch—in part due to the genuine relationships I’ve created with colleagues there. But it’s not the first time an app has imploded. Vine, the app where people uploaded very short-form videos, launched in 2013 and abruptly ended in 2017—yet many of its influencers didn’t disappear.

Lorenz talked to me about the rise of social media influencers, the “creator economy,” and what Elon Musk seems really not to get about why people liked Twitter.

Before the social media platforms of today, there were bloggers. How did misogyny impact the way people perceived the early blogging era, including who was judged for monetizing their blogs?

The first blogs were not very personality-driven at all: It was mostly themes like politics, tech, things like that. Of course, no one cared when they monetized, really. But when mommy bloggers did it, there was a mass backlash. When [early mommy blogger] Heather Armstrong posted in 2004, saying, “Hey, guys, this is a full-time job for me, and I need to get paid, so I’m gonna put banner ads on the website”—which is something that today would be the least controversial thing you could do—she was met with such vitriol and backlash. There was so much misogyny when they were doing the most simple things like posting selfies.

How has the inclusion of advertisements and sponsored posts legitimized being a “content creator” as a career and as part of the economy?

YouTube basically instituted the Google Ads model onto video. Once YouTube was acquired by Google, they were running Google Ads, which became the partner program where they did this revenue-sharing model with their content creators. It was truly revolutionary at the time. I think that’s why, today, YouTube remains the most stable of any of the social platforms in terms of income-sharing. It did help legitimize the industry.

Influencers’ lives and content may not be exactly what they seem—for example, improperly disclosed spon-con from beauty influencers on TikTok. How can their “relatability” lead viewers to trust them excessively?

People have parasocial bonds with these content creators. You do know a lot about their lives and personalities. You almost feel like they’re your friend, even in just a light way. You’re often following content creators highly tailored to your own personal interests, ethnic background, gender, or ideology, and so you feel very close. It’s a deeper connection than reading [ads by] a faceless media brand in terms of building trust. You go to a magazine, you don’t even know who wrote that [product] review. That’s probably spon-con too—undisclosed—or they have a relationship with it. It’s hard to trust. So I think people turn to these content creators.

You trace the rise and fall of social media platforms such as Vine. What has Elon Musk missed about the rise of Twitter that’s led to whatever its current state is?

Elon Musk makes the classic mistake pervasive among Silicon Valley executives, which is a deep disrespect for their users. This is how Clubhouse died. It’s how Vine died. This is how app after app is killed by Silicon Valley hubris: “I don’t care how users want to use this product. I’m going to tell them how to use it, and I’m going to decide who’s popular on this app.”

Of course, social media apps will boost people that they think might be interesting to users, but you can’t force-feed users content that you want them to see. Overall, that’s not going to be a compelling app to the majority of users, and so it is going to fail. Elon is learning that lesson the hard way. He’s alienated all the big content creators. Twitter’s an ideological project for him. It’s not about building a sustainable business.

Looking at the future of influencers, why is it important that many have outlasted the platforms they started on?

Creators are getting less and less platform-dependent. Vine is this pivotal moment because prior to that, that wasn’t the case. People were very platform-specific. Once all those Viners went to Facebook and then YouTube, this myriad of apps popped up. So you’ll have an app that you build your audience on, but you immediately then try and diversify your following across platforms. [What] a lot of people learned from the Vine era, or what’s going on with Twitter, is you should not put all your eggs in one basket. I think this is a lesson that a lot of journalists are learning for the first time now—because most journalists have way over-indexed on Twitter.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.