On Monday, Bill Walton, one of the greatest basketball players of his generation and a hippie prone to looping flights of verbal fancy, passed away at age 71 from cancer.

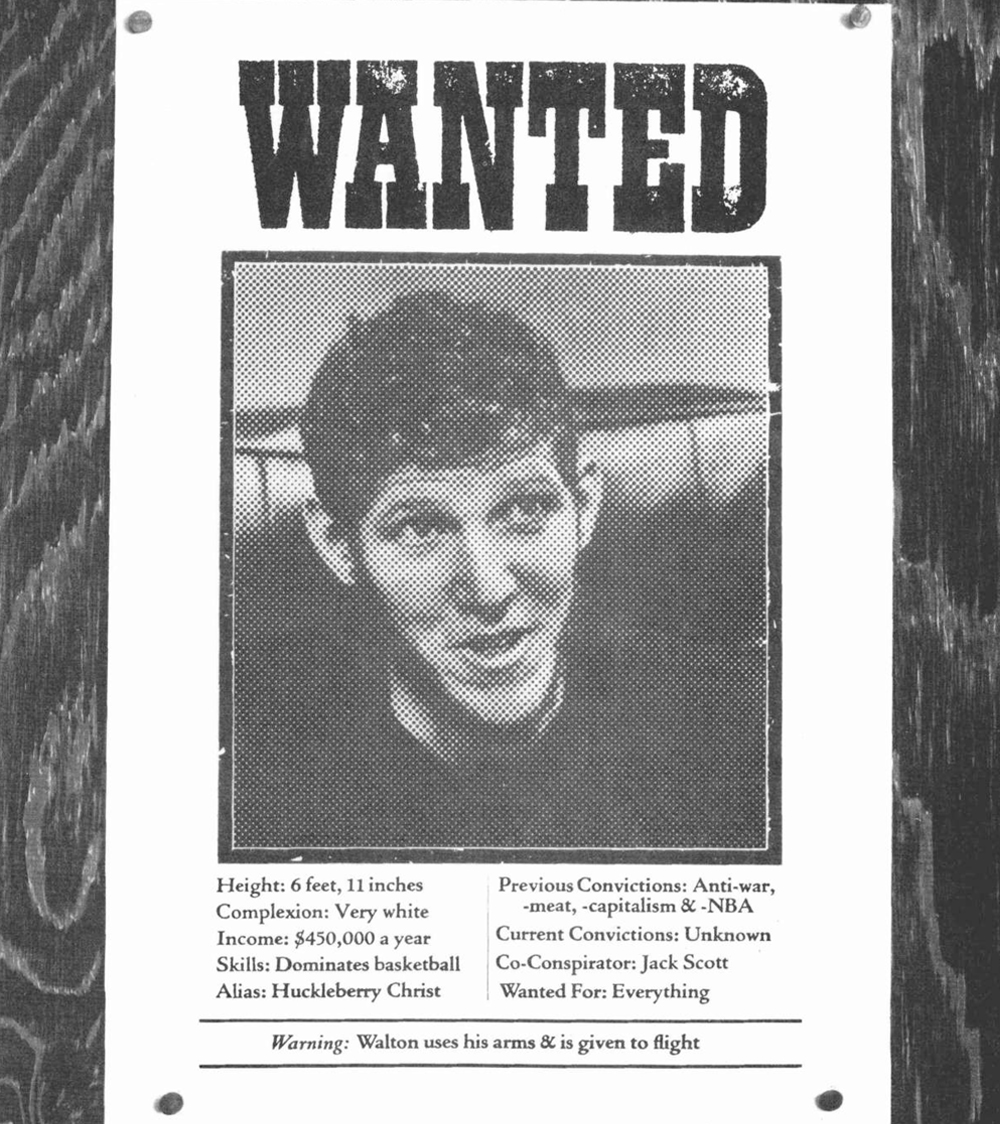

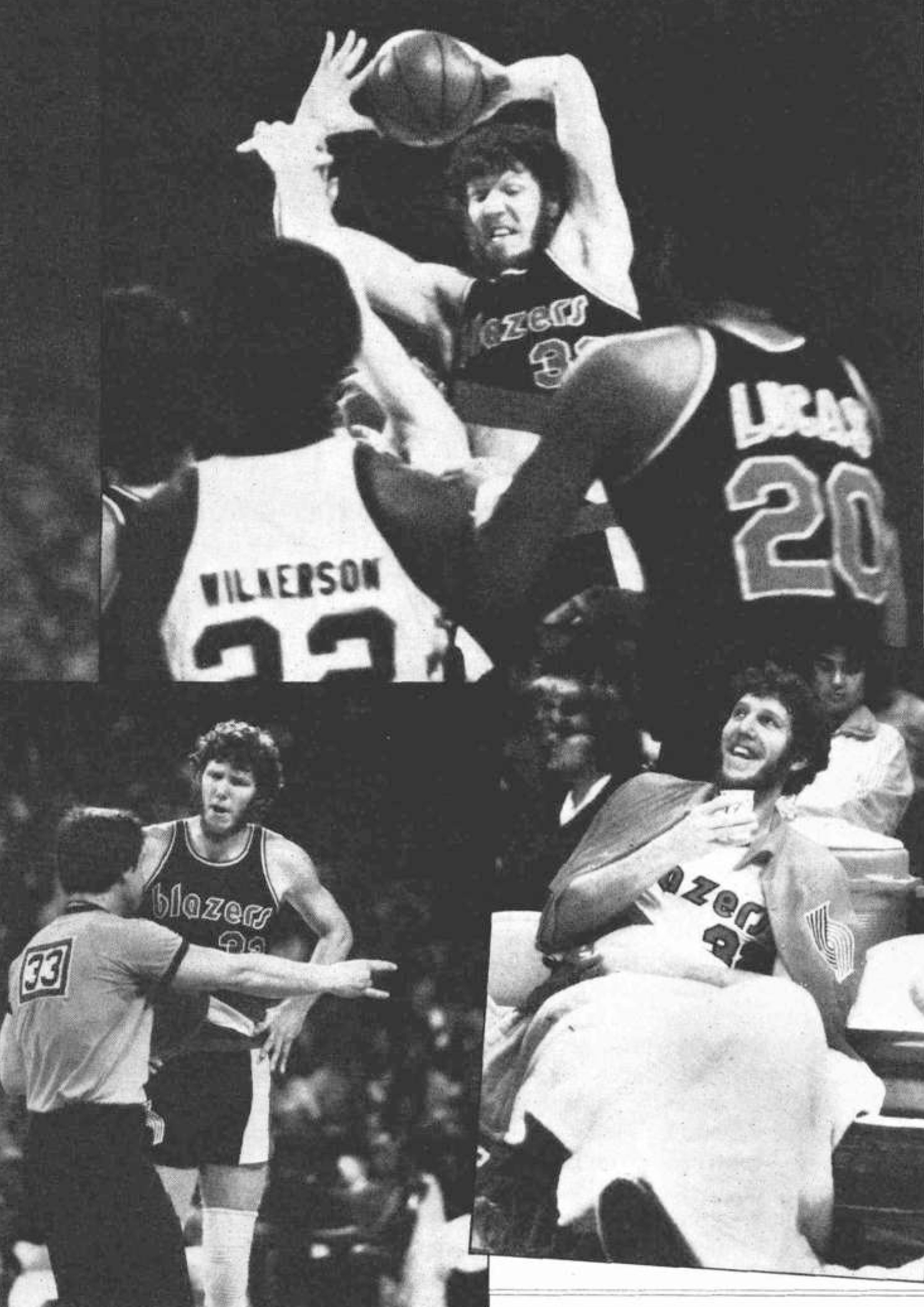

A Grateful Dead fan who was arrested protesting the Vietnam War, Walton graced the cover of the September/October 1978 issue of this magazine. Below, you can find a version of that story: “Searching for Bill Walton.” It documents his mercurial relationship to stardom during his heyday with the Portland Trailblazers.

“Welcome to pretty little Portland,” the flight attendant says, “home of the World Champion Trailblazers.”

Prominently displayed in the airport is a Trailblazer flag. The airport bus driver can’t name her favorite player because she has four, all of whom she loves equally. We drive under a bridge emblazoned “Go Trailblazers.” The first meal I have is a Trailblazer burger.

With about 500,000 people, Portland is the smallest metropolis in the National Basketball Association, in June of 1977, some 250,000 people crowded the downtown area for the Trailblazers’ victory parade. The final playoff game the day before was, of course, sold out; scalpers hawked standing-room-only tickets for $100 each. Luckily the game was broadcast on national TV; ratings showed that 96 percent of the Oregonians turning on their sets that afternoon watched their team’s victory.

Their team. Not one of the Trailblazers was born in Oregon, or went to school or college there. The coach spent his previous 20 years directing Eastern teams. The owner lives in Los Angeles. During his first years in Portland, Bill Walton, the superstar, hated the area’s continual rain, disliked many of his teammates and mumbled about wanting to be traded if he didn’t quit professional basketball altogether.

Walton’s less-than-love affair with Oregon was mutual. Fans and management wondered if his early ailments weren’t due to his vegetarianism; when he refused on principle to take drugs for a supposedly painful bone spur that kept him out of games, they suspected him of malingering. Then Walton literally added insult to injury by supporting Jack and Micki Scott, harborers of Patty Hearst. At the close of the Scotts’ press conference, Walton said: “I would like to reiterate my solidarity with Micki and Jack and also urge the people of the world to stand with us in our rejection of the United States government.”

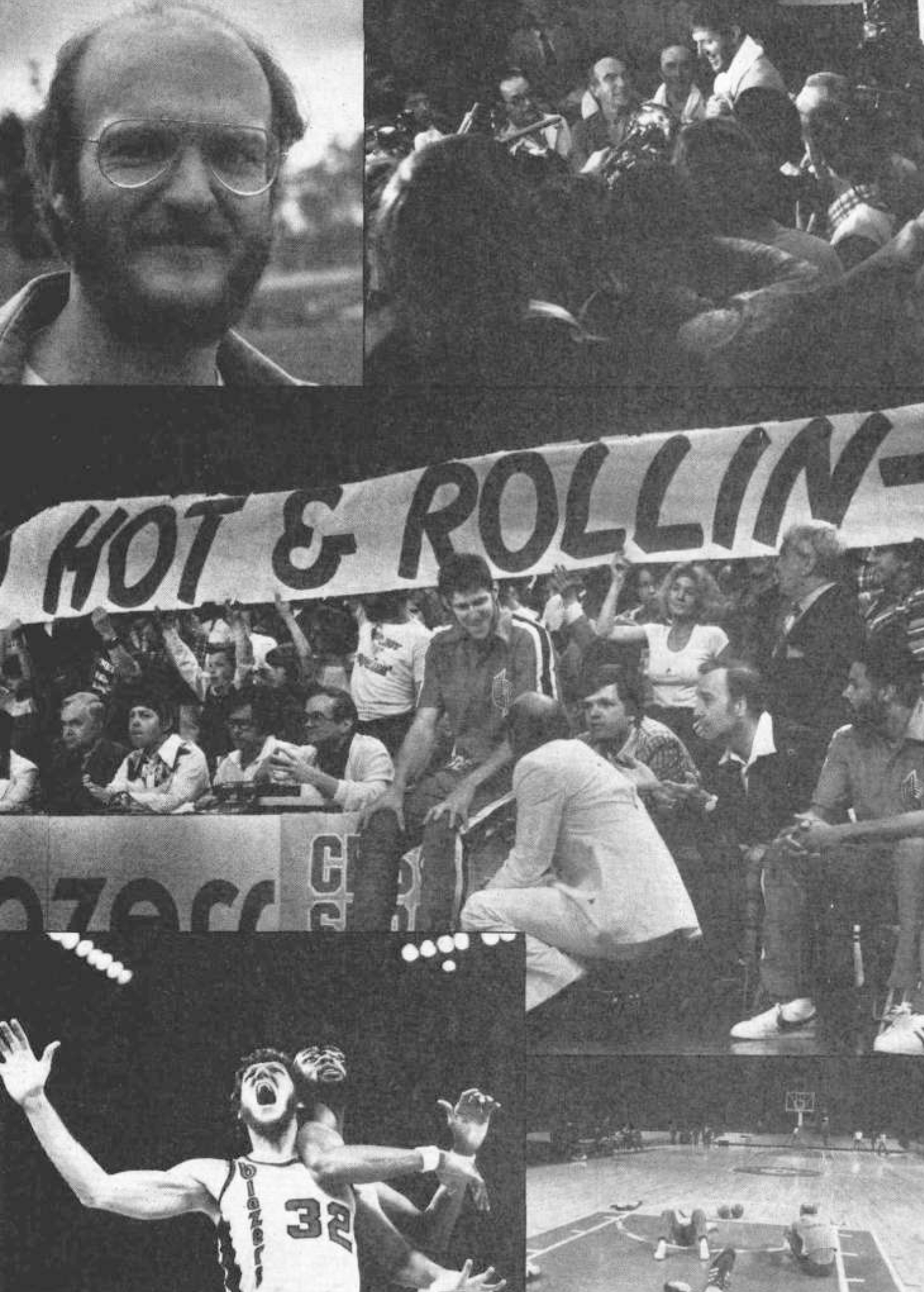

But all this bitterness, as sportscasters are wont to say, is ancient history. The year the Trailblazers won the World Championship, fans sang “Happy Birthday to Bill” in the middle of a game. Small wonder: out of the 47 home games Walton played in that year, the Trailblazers won 45. Contests and polls showed that he had become by far the most admired Oregonian—and the most popular basketball player in America. The hippie was finally earning his $450,000 annual salary. He still didn’t talk much publicly, but at least he no longer seemed condescending. Hell, he appeared downright happy. When crowds greeted him and the team at the Portland airport, Walton smiled and reached down to shake hands. When the final buzzer sounded he hurled his shirt into the stands. In the locker room he poured champagne over the coach, and at the parade the next day he poured beer over the Mayor. Although Blazermania was launched anyway, Big Bill Walton christened it.

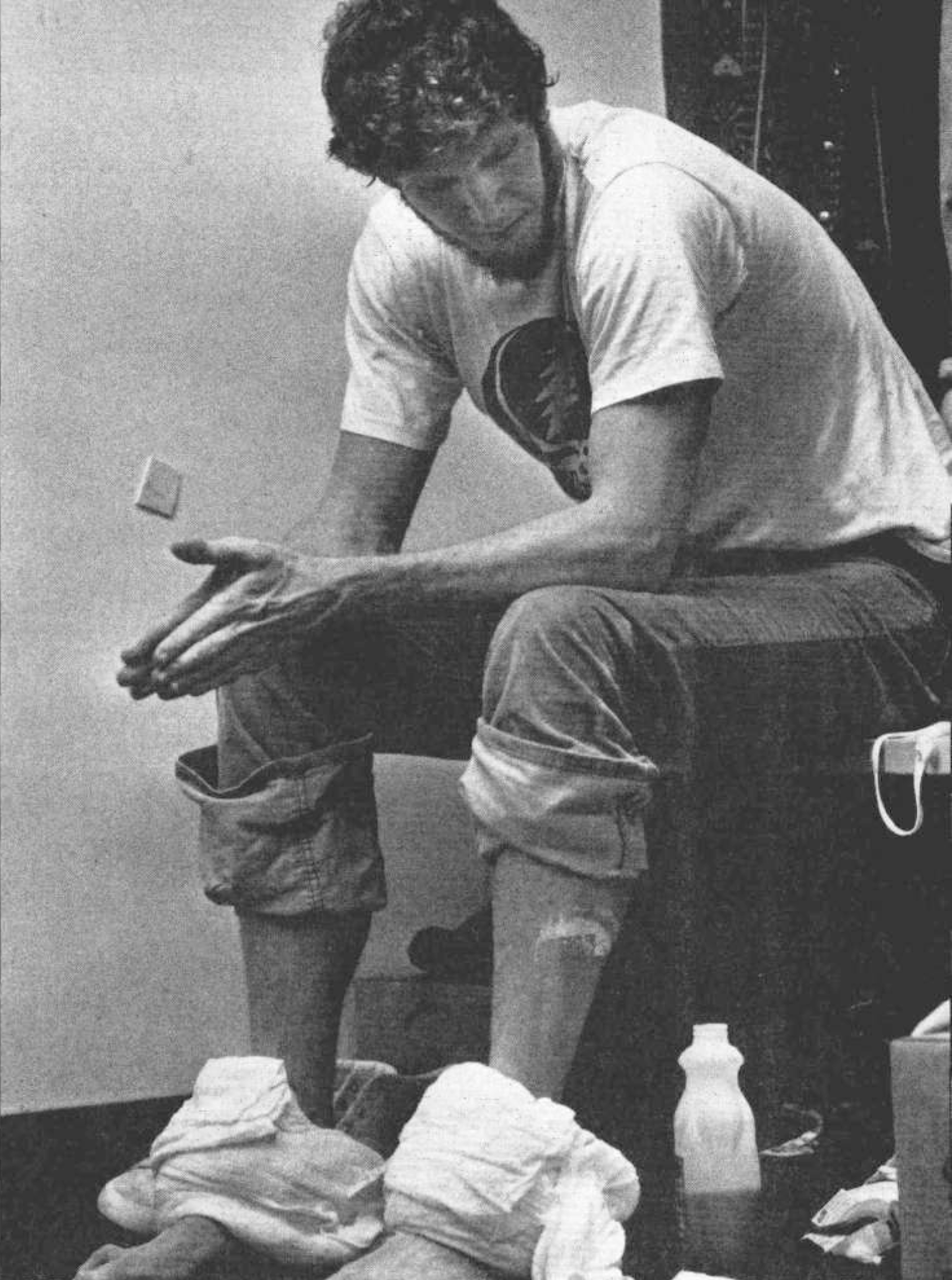

One year and 50,000 Blazer Tshirt sales later, the team is a game away from being eliminated in their playoff series against the Seattle Supersonics. One starter, Bobby Gross, has been lost with a broken leg. Another key player, Lloyd Neal, is out with hobbled knees. And Walton is sidelined with a fractured left ankle.

“Sidelined” is misleading because, unlike the other injured players, Walton hasn’t been showing up at the playoff games to cheer his team on. No one knows exactly why. Is he rejecting Portland again? Is he angry because—against his own instincts and philosophy—he let the team doctor shoot him up with a painkiller right before he fractured his ankle?

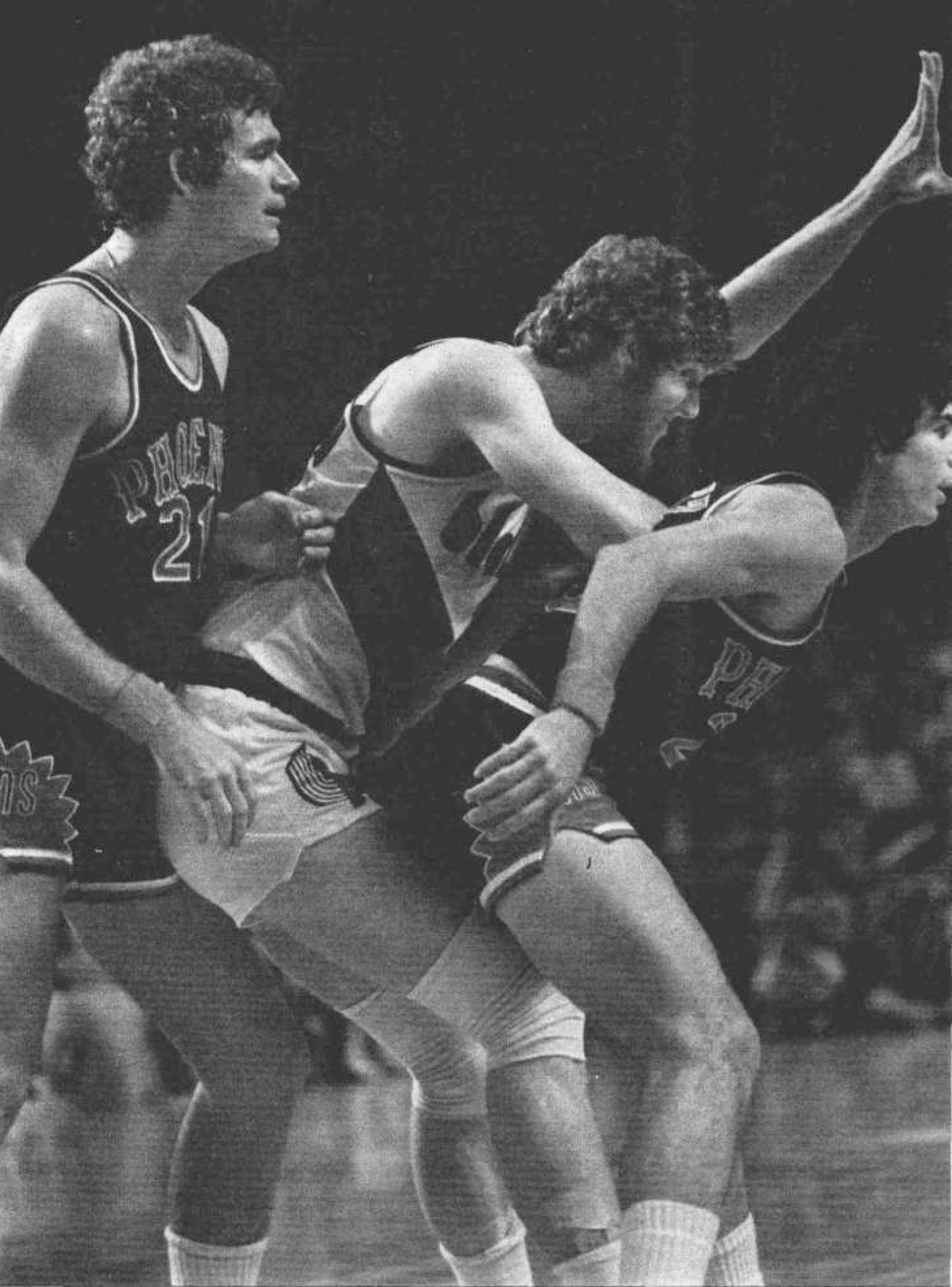

The Trailblazers wander onto the Portland Coliseum court in sweatsuits for their final practice. With the redheaded white hope gone, the dominating figure is Maurice Lucas, a six-foot nine-inch black known as the pre-eminent “power forward” in the league. He’s also known as Walton’s protector on the court. Lucas meditates before games in order to feel sufficiently angry and aggressive. Today, however, he seems the loosest on the team. When Portland’s mayor arrives to watch the practice, Lucas mocks his pot belly.

Coach Jack Ramsay comes on the court and goes through the stretching exercises with his team. His body, that of a lithe 30-year-old, contrasts with his bald head and worried face.

The team now performs fast-break drills. The sportswriters sitting in the otherwise empty stands have seen this hundreds of times before. They are gossiping about sportswriter John Bassett’s recent stories: in Willamette Week, a liberal newspaper, Bassett has exposed the drugging of the Trailblazers and the press’s cowardly refusal to criticize the team management.

The Trailblazers’ general manager, Harry Glickman, now comes into the Coliseum and asks Jack Scott if they can have a private word. The “word” turns into a half-hour talk. Glickman wants to know if Scott has seen Bill Walton lately. Walton apparently isn’t answering his phone. Where is he? How is he feeling? Depressed? Angry? A basketball magazine wants to present Walton with its Most Valuable Player of the Year award at half-time tomorrow, and of course the game is going to be broadcast on national TV. Does Scott think Walton will show?

When the practice ends, leotarded little girls from a tap-dance competition next door swarm around the players and ask for autographs. In the locker room everyone autographs new basketballs—for a hospital, for a charity auction. The atmosphere in here is more polite and less overtly macho than in any college locker room I’ve visited. Because of their characteristic restraint—along with their teamwork and the fact that only seven of their 12 players are black—the Trailblazers are perceived as an essentially white team. Conversely, their championship opponents last year—the showboat, high-flying Philadelphia ’76ers—were seen as not white. High school and college coaches all over the country feared that if the ’76ers won, no coach would be able to control his players again. Walton’s own misgiings toward authority were forgiven because, when the chips were down, he apparently put aside his politics and came through for America.

“I talked to your friend the other day,” the Trailblazer trainer tells Jack Scott. “And I do mean I talked. He didn’t say a word. … Tell me, how’s he feeling? Is he really down?”

With the Crown Prince incommunicado, Scott is back in a familiar role. Management makes overtures to Scott as if he were a Saudi Arabian middleman. They’re not sure if Scott is a real negotiator or merely self-appointed, but given how baffled they are by Walton, it’s worth trying anything to get through.

Scott now carefully notes that, although he has spent time with Bill recently— indeed, last night they watched television until 3:00 in the morning—he can only say that Bill seems naturally depressed, and he has no idea whether Bill will appear for the game tomorrow.

“Liar! You write lies! You write untruths!” Coach Ramsay suddenly yells at John Bassett. “We don’t welcome liars in our locker room!”

Bassett blanches; Ramsay is irate. A mottled red spreads over his face. He paces the locker room, looking as if he might have a heart attack. Bassett follows cautiously, saying, “If you’ll just tell me one lie I wrote, I’ll…”

“Liar! You’ve done nothing but denigrate this organization from the first.”

The players watch nonchalantly. Afterward they discuss how they’ve never seen their coach so mad. Maurice Lucas comes from the showers and announces, “I’m not a beggar, but I can smell a roll. There’s a rumble going on out here.”

Bassett follows Ramsay, but the coach has contained himself. He won’t say a word. Bassett stands alone in the middle of the dressing-room floor—a forlorn scapegoat. Ramsay comes over to Scott and explains, “I don’t mind criticism, but that man wrote untruths.”

Scott listens with a pained, sympathetic expression. He agrees wholeheartedly with John Bassett that the team doctor, and ultimately the owner, were more than negligent when they injected Bobby Gross, and later Walton, with painkilling drugs. These players would never have broken their bones if they’d first felt the warning signals of pain from their bodies.

And yet Scott doesn’t wish to confront Ramsay. The coach is adamant that the management has done nothing wrong and that Walton isn’t angry. That isn’t why Walton is staying away. After all, Ramsay talked with him just this morning, though Bill wouldn’t say where he was calling from. “Do you,” Ramsay asks Scott, “by any chance know?”

Later that afternoon Coach Ramsay and General Manager Glickman bump into each other in front of Walton’s house. Both are pretending to be dropping by casually. But the landlord tells them, as he tells me and Scott later, that Walton has fled to his country farmhouse with his woman friend, Susan, and their two children.

So it seems likely that Walton won’t attend tomorrow’s game, and that one of the CBS broadcasters will label this absence as poor sportsmanship. It isn’t clear which the Trailblazer management is more worried about—upsetting the fans or irritating Walton. The relationship between the fans and Walton, however, is worth worrying about. Before Walton came to Portland, the team had 2,971 season ticket holders. Three years later, after the Blazers won the championship, more than 18,000 people applied for year-long rights to the 12,666 available seats. Substantially raised ticket prices didn’t diminish demand; three federal judges presided over a drawing for seats that was watched more closely than the pre-Walton Trailblazer games.

One would think that the owner, the general manager, the coach and the team doctor would treat so valuable a commodity as Walton with extreme care. “Believe me,” Scott says when we part that afternoon, “the owner, Larry Weinberg, calls the shots, and he thinks that Bill is injury prone. He wants to get his money out of Bill quickly because he doesn’t think Bill will be able to play the game for very long.”

Would Walton be injury prone if he wasn’t urged to play when injured? The Portland management resents discussing this question. They’re not even willing to say that they made a mistake in the more clear-cut case of Bobby Gross. Because he had severe pain in his ankle, Gross was injected with the anesthetic Xylocaine prior to at least seven games. When after several weeks the pain hadn’t subsided, and the shots necessary to numb it had escalated to three, Gross asked that x-rays be taken. Since the team was in the middle of a hectic road trip, the doctor said to wait until the next city . . . and then said to wait until the next. When in the middle of a game Gross finally snapped the bone above his numbed ankle, he told reporters, “I didn’t feel a thing. I only heard the noise.”

This seems so incredible that I call Gross to confirm it. “Well, not exactly,” he says. “When the bone broke, something felt a little warm.”

Later that night, another player tells me: “Bobby was jumping up and down on a stick. The company doctor could dope up a cripple to run down the court. But where is his foot? Back under the other basket.”

This player and I are sitting in the hotel room of a very wealthy fan, Randy, who has flown in from New York for the next day’s game. Randy, who has played a little ball himself, is a connoisseur of the game and a friend of at least a dozen NBA players. These friendships are in part cemented by Randy’s generous sharing of cocaine.

Randy pours some coke onto a mirror and begins breaking it down with a razor into lines of fine powder while he and the player share NBA gossip—who is unhappy, who might be traded. Randy then snorts some cocaine and passes the mirror around. The Trailblazer inhales a very small amount. He wants to relax tonight, not get terribly high.

If pain relievers like Butazolidin and Xylocaine are NBA trainers’ favorites, cocaine is the players’ drug of choice. Although the Trailblazers are not the cookies-and-milk-before-bedtime team that some Blazermaniacs would like to believe, their drug cohsumption is probably below the norm. Randy nods frequently as I question him about snorters on the starting lineups of various Eastern teams. I myself know of several users; one friend who cleaned house for a Golden State Warrior said that every visit she also cleaned the cocaine spoon by his bed.

Why cocaine? First, NBA players make a lot of cash, and coke is the high of conspicuous consumers. Second, coke promotes bodily confidence. During road trips and the long season, players need to feel good about themselves. Unlike speed, coke doesn’t delude them too much about their abilities; and if they use the drug judiciously, they’re not too likely to crash. If cocaine affected performance, management would have offending players busted. But what worked for Peruvian Indians works for the NBA.

“If they bust a player,” Randy tells me, “you can be sure that someone on top wants him out for other reasons.”

“Look how they’re harassing Leon Spinks now,” the Trailblazer with us says. “Spinks isn’t going to be heavyweight champion long unless he figures out who he’s offending. Someone better wise him up to all the rules of the game.”

The fifth game in the Portland-Seattle playoffs is on the Sunday beginning Daylight Savings Time. One of the parking attendants who collects dollars has forgotten to set his clock ahead, and when he arrives his lot is already full. The fans know what time it is—even though this is Portland’s 87th game of the year. This does not include the eight-game exhibition schedule. The teams that reach the final playoffs can end up playing as many as 114 games in a season stretching over nine months.

The Trailblazers’ trainer has done studies showing that most player injuries take place in the later games; the season is simply too long for the human body, and there isn’t enough time to recover in the summer. Yet the owners say they need this many contests to recoup the $110,000-a-year average salary they pay each player. And players will tell you they deserve what they earn given the length of the season, the stresses of the game and the likelihood that injuries will prematurely end their careers.

Although the players are profoundly fatigued, they don’t need drugs to get up for today’s game. More than 12,500 fans pour adrenalin into their systems. The crowd is already pumping it during the warm-ups. In the press room, several reporters approach Jack Scott and casually ask, “Is your friend coming?” Outside, most fans that I talk with are resigned to the fact that Walton won’t appear. The older Blazermaniacs seem especially resentful: “The leopard can only change his spots so much.” My favorite response, because it mirrors Walton’s own posture, comes from an old-fashioned hippie: “I’m sure Bill has better things to do.”

The opening tip-off is won by Seattle, and a series of bad passes, fouls and other violations ensues. After almost half of the first quarter the score is tied at a dismal 6 to 6. Both teams are playing very tensely. But then when Portland seems to realize they aren’t going to be overpowered again, their coaching and teamwork start to pay off. They score seven baskets in a row. The crowd shakes itself alive; maybe the clocks are still on Blazer time. “If we win this game, we can win the next, and…”

To millions of Americans, searching for a connection with Bill Walton (and Jane Fonda, and Bob Dylan, and . . .) has become a mythological quest.

The Portland basketball crowd is the most informally dressed and whitest that I’ve ever seen. I can pick out more black faces on the court and the security force than in the arena’s sea of plaids. Soon I move next to a black spectator; he’s a Blazermaniac, but he also gets upset when the white referee calls a foul against one of Seattle’s black players. During a time-out we talk about Portland’s racism, which he thinks is getting worse each year. “Of course when the team is winning, everything is peachy. But just last season the fans right around me were yelling ‘nigger’ at Lionel Hollins. I heard it with my own ears. After the game they’d put notes on his car or let the air out of his tires.”

Play has resumed, and the fan wanders from our conversation to cheer his Blazers on. Portland continues to gain momentum. The fans raise their fists, stamp their feet, jump up after each basket, applaud continuously through the time-outs. After the Trailblazers open up an 18-point lead, the crowd claps louder and louder to celebrate itself.

CBS’s guest commentator, basketball star Rick Barry, says on TV that although he has supported Walton through all his previous trials, he can’t forgive the redhead for not showing up.

The Blazer who snorted coke last night is performing well. But the two stars are Tom Owens, Walton’s back-up, and Willie Norwood, a journeyman acquired at the end of this season to fill in for the lost regulars. The home town team’s “team” victory is thus slightly ironic. Owens has played on seven different squads in the last seven years, and Norwood was very recently a Seattle Supersonic. In the locker room after this game, Norwood confides that before the opening tip-off he almost went over to his old teammates by mistake and said: “Hey, let’s get ’em today!”

Still, the Trailblazers have played a coordinated game, and the Supersonics have lost as a collective unit. Outside the Sonics’ locker room, their coach tells reporters: “We didn’t deserve to win. Our players didn’t show maximum desire.” Coach Ramsay is also laconic: “We won because we played our game.” These speeches serve as the backbone of a dozen newspaper stories the next day.

In between the fifth and sixth playoff games, I drop by Jack Scott’s house. Initially I decided to visit Portland because of Scott. Reading galleys of his book, Bill Walton: On the Road with the Portland Trailblazers (Crowell), I was intrigued and repulsed. Scott has been a central figure in most of the sports controversies of the past decade: he reported early and favorably on the revolt of black athletes, and subsequently got the blacklisted Olympic sprinter Tommie Smith a job as track coach; he taught the first university course on “Sport and Society,” then maintained an institute of the same name from which he counseled disenchanted athletes; as Oberlin’s athletic director, he upset bureaucrats by scheduling more activities for women, by not charging admission to collegiate games and by opening up campus facilities to the community.

I admire Scott tremendously for all of these efforts; yet in his latest book he comes across as a pushy, rather than a graceful, activist. Describing his travels with the Trailblazers, Scott is by turns sycophantish, good-hearted, self-serving, shrewd, long-winded, whining and thoroughly loyal to the players.

Many people nonetheless see Scott as a Rasputin. He almost looks the part. A former basketball and track star, his bald, egg-shaped head makes him appear older than his 36 years. Occasionally Scott strides like an athlete. But around the Trailblazers he more often sidles into encounters. While several players and Blazer officials like Scott, he is treated in a special way because he is Walton’s friend. The media always refer to Scott as a “sports activist” because his activism has led to no permanent job. What little chance Scott had of being hired by some university was destroyed by his association with the SLA. Now Scott must live by others’ generosity and his own considerable wits.

Tonight the local media persist in calling Jack at his home to ask his opinion on why Walton didn’t come to the game. Several reporters from national publications call to see if Jack can arrange a meeting with Bill. A few don’t know that the Scotts and the Waltons no longer live together. After two years in the same house, they’ve moved a couple of blocks apart. Jack says that he and Bill made a non-verbal agreement to stay with each other through troublesome times; when Walton adjusted to the NBA and when the FBI stopped hounding the Scotts, it was natural for the two families to move apart. Others in Portland say the move also reflects Walton’s drift into the upper middle class and beyond. He has cut his ponytail, speaks out on fewer issues, has bought a Mercedes (previously he scorned expensive cars), restricts his donations and is no longer considered locally a wild and wonderful hippie.

Jack refuses to criticize his friend—which is a main reason his biography of Walton is stiff. The most Scott will say is that recently he’s been as close to Maurice Lucas as to Bill. And that this latest drug-related injury may make Bill a little humbler and remind him of some of his earlier beliefs.

The next morning a sports columnist named Augie Borgi writes an open letter in The Oregonian: “Dear Bill Walton: I hope you were near a TV. . . . Your good friend Jack Scott told me before the game about how serious the breaking of your foot was. But you did miss something, maybe even the start of something.” The writer then goes on to detail the Blazers’ triumph yesterday. Although he’s trying to jab at Walton for not showing, he gets so carried away describing the game that he ends up forgetting his open-letter format.

Also in The Oregonian is a story headlined: “Walton Advised to Miss Playoffs.” In the afternoon competition paper, there’s an identical piece with the headline “Walton ‘Wanted to Come.'” Both explain how Coach Ramsay and Team Doctor Cook told Walton not to attend yesterday because he is wearing a cumbersome leg cast and is suffering “mental anguish” thinking he let his teammates down. This item is amusing because the desperate Blazer management has been unable to locate Walton to tell or ask him anything; it’s also a touching fiction because it indicates how unhappy Oregonians are living in tension with their hero.

As Scott and I drive out to see Walton, we hear an announcer on the radio say that he understands how Walton feels he let the team down. If Bill is listening, he just wants him not to worry: “You’ve given us enough. Just take care of yourself. We know you’ll be rooting at home during tonight’s game.”

Scott is slightly nervous and distracted. He’s taking a risk in bringing me to Walton. After all, Walton hasn’t been answering his farmhouse phone. He’s probably not up for seeing friends, let alone strangers, let alone reporters. I’ve pressured Scott by appealing to our common politics. In a dozen ways I’ve tried to indicate that Mother Jones isn’t interested in ripping Bill Walton off.

Anyway, what the hell am I likely to discover? Walton is a star because of his six feet eleven inches and the way he plays basketball. When he gets a defensive rebound, he’s better than anyone in the NBA at passing the ball off to a teammate who’s starting a fast break. On offense, he spots openings so shrewdly that his opponents never know whether he’s going to drive, pass off or shoot. Walton doesn’t have a stunning political philosophy, or mystical insights into the evils of meat; like thousands of other middle-class Americans who came of age in the late ’60s and early ’70s, he’s just a leftish vegetarian.

Yet to millions of Americans, searching for a connection with Bill Walton (and Jane Fonda, and Bob Dylan, and . . .) has become a mythological quest. In a reality that’s easy to disparage but hard to overestimate, Walton has developed into a kind of Huckleberry Christ. Although Walton is not so calculating as Jerry Brown, his similar anti-grandeur stance only intensifies the public’s desire to exalt him. You can take the salt off potato chips and call them natural, but fans still keep munching away. We now stop at a health-food store on the outskirts of Portland. The ancient Greeks brought along gold and sacrificed sheep; Jack Scott buys a large jar of fruit juice for later use as an offering.

Although Walton’s country place is only 50 minutes from downtown, it’s not directly off a freeway. We go from city streets to a highway leading over a narrow bridge to a country road, then onto freeway and back off to a country road again. Scott’s casual, nervous, alert style adds to the suspense. His speech is littered with “you knows,” yet his directions and sense of traffic (“If it’s backed up after this next turn, then we’ll hit more congestion in another 15 minutes and. . .”) are precise. This is the man who eluded the most extensive FBI manhunt ever. With 8,500 agents searching for them, he drove a terrified Patty Hearst across the country. General Teko, born Bill Harris, castigated Scott for his bourgeois attitudes, yet the General couldn’t get himself out of Berkeley. He ordered/begged Scott to fly back from the East, and they traveled across the United States posing as a gay couple. Scott is a master of disguises. While with Patty, he carried along two tennis rackets so people would perceive them as at leisure.

Scott and I now talk about Scranton, Pennsylvania, the decayed coal-mining city where we both grew up. Scott is the only radical I’ve ever heard of from his side of town. The white ethnics of Scranton are poor, generous, cagey, violent and quite friendly. Jack Scott was a tight end on his high school football team; he was fast and he liked to hit. This love of contact seems to be the constant bridging Scott’s conversion from Goldwaterite to socialist. If he sees an opening in America’s defensive backfield, he tries to run into it; it doesn’t matter what end of the line he starts from. If a hypocritical linebacker (a Phys. Ed. bureaucrat, an FBI agent) is in his way, he’d just as soon smash into him. Also, Scott remains loyal to whoever (including the SLA) is supposedly playing on his team.

When we drive up to the farmhouse, Jack tells me: “If they were inside, I’d have heard Adam and Nathan White Cloud [Bill and Susan’s boys] by now.” Soon Jack hears a motor in the distance. We walk toward the sound until finally through an opening we see Walton. It’s as if out of Faulkner’s The Bear: “It did not emerge, appear: it was just there, immobile, fixed in the green windless noon’s hot dappling, not as big as he had dreamed it but as big as he had expected, bigger, dimensionless against the dappled obscurity, looking at him.”

Walton is perched atop a baby tractor much too small for him. His legs—one in a cast—jut out as if he were in a go-cart. He peers at us, recognizes Scott, waves. Then he resumes his mowing. He urges the tractor as fast as it will go, which isn’t very fast. Grinning in his characteristic self-absorbed way, he continues blowing off steam on his own country court.

Scott and I chat. Eventually, when the tractor stalls, we approach. Walton removes crutches from behind his seat, dismounts and very gracefully lowers himself under the machine to see what’s the matter. When he re-emerges, Jack introduces me as a friend from Scranton. In public Walton often lowers his gaze to avoid other people’s stares and requests. Now he checks me out very directly.

“Did you hear about the fight in the locker room?” Scott asks.

“Nope, I haven’t heard a thing.”

“Well, Ramsay started yelling at Bassett, calling him a liar. ‘You write lies! You write untruths!’ After a while he just, you know, left Bassett standing alone in the middle of the locker room. He wouldn’t even talk to him. Luke banged some metal and pretended, you know, that it was a prize fight.”

Walton laughs at this choice bit of gossip. He leans back against the tractor. He’s wearing an old cranberry color pullover sweater. His red hair has been clipped for the summer, but his beard is as scraggly as ever.

“Did you see Augie’s column in this morning’s paper?” Jack asks.

Walton nods his head yes.

“Well, believe me, I didn’t talk to Augie Doggie. He just, you know, overheard what I was saying, and he misquoted me on top of that. I called up the paper this morning and gave his editor hell.”

“When I see Augie Doggie,” Walton says sternly, “he’s gonna get a piece of my mind.”

Scott now goes back to fill in more details of the locker-room fight. Walton listens with an open-mouthed grin, slowly climbs back onto his tractor and ends Scott’s narrative with his judgment: “Sounds bizarre.”

Walton’s limited curiosity about the frenzy surrounding him is also bizarre. Then again, why shouldn’t the Trailblazers’ center and the center of Oregon’s attention be self-centered? As he tootles off over hillocks to park his tractor in the barn, his body gently bumps up and down. The small, fluttering aspens that frame this rear view of Walton make him appear a peaceful giant.

Walton comes out of the barn on crutches. Passing by us he says, “I’ve got to get ready ’cause we’re going out for supper.” He nods to me as if to say it’s been nice meeting you. Scott tells him, “Jeffrey, you know, writes for Mother Jones.” Walton does a doubletake: You brought a reporter here?

But after he realizes that I’m not going to ask him if he’s in “mental anguish” or whether he thinks the Blazers will win tonight, Walton becomes hospitable. He meets us in the farmhouse living room, and we all drink the Machu Picchu fruit-juice blend Scott has brought along. There are mattresses on the living room floor; for furniture there are large pillows covered with South American hand-woven fabrics. Walton sits down and leans against the wall. Curly-headed young Adam plays around his father’s long legs. We chat about horseback riding, the countryside and the weather—where the clouds generally break and Oregon becomes drier. The atmosphere in this room is lowkey. Because I’m a friend of Jack’s, Walton is willing to shoot a little breeze. But it seems difficult for him.

I feel as if I’m visiting the Wizard of Oz—except Walton’s appearance is so unusual that he doesn’t need to hide behind a curtain and manipulate throttles to make his breath steamy and his voice booming. Articles about Walton invariably describe him as “enigmatic.” Probably the only thing enigmatic about him is his determination to remain withdrawn in the light of so many projections. By nature Walton is a shy, ordinary fellow, and by will he wants to remain this way. He’s forever snubbing the munchkins who want to sing about the wonders of Oz.

Susan comes in with their infant, Nathan White Cloud. Although she and Bill have lived together for several years, they’re not legally married. Neither for that matter are Jack and Micki. Susan tells Bill that if he wants to change his pants for dinner, he’d better do it soon.

Susan has healthy, attractive looks and manner. When Bill leaves, she picks up the conversation. Yet she doesn’t ask who I am or why Jack has come out today. She has said that most people give 95 percent of their attention to Bill, four percent to their children and one percent to her. Small wonder that she wants to build a more traditional family life and obtain some security by settling down.

Although on crutches, Walton quickly covers the 100 yards to and from their bedroom “shack.” He reappears after changing from jeans into faded tan corduroys, which Susan has just washed.

“Are those cords nice and fresh?” Susan asks.

“Yeah, they’re nice,” Walton says and adds, a full minute later, “real nice.”

Then they are off. Although all of Oregon is yearning to know whether Walton is enraged or suicidally depressed, he doesn’t ask his friend Jack Scott what’s going on in Portland. He doesn’t inquire about the team or the Blazer management. He doesn’t seem curious about why we’ve come out; nor does he say anything about our leaving when he and Susan are gone.

As we walk to our car, I ask Scott if this is a typical encounter with Walton. “Well, you know, Bill’s not too talkative. Sometimes I’ve spent whole evenings with him when, you know, he just says a few sentences. But for a minute there he, got pretty angry at Augie Doggie. That’s rare. He almost never gets so mad.”

Driving back from Walton’s, I feel queasy about the trivialness of our encounter. I haven’t gotten what I was hoping for, though I think I’ve found what’s there. Walton isn’t a guru playing games to educate America; nor is he Jack Scott’s puppet. He knows what he’s doing—and his main goal is to satisfy himself. Walton is staying away from the playoffs because he’s disappointed and doesn’t want to be hassled. This is understandable. From any political perspective, it’s also selfish. Furthermore, a black star who acted this way would definitely be traded, and a black superstar would at least suffer financially.

Judging Walton’s absence from the playoffs—indeed, judging Walton at all —takes the fun out of hero worship. What a letdown that Walton and his motives are banal. If he’d turned out to be Scott’s fool, a fan could at least get incensed. But the two appear to have a genuine give-and-take. Scott uses Walton as a glamorous vehicle for his ideas; and Walton uses Scott to run interference for him.

That night I watch the final Blazers-Sonics game in a bar on Portland’s north side, Walton’s neighborhood. Elevated in one corner is an Advent projector that relays its television images onto a home-movie-size screen, The bar tonight looks like an advertisement for a premium beer eager to capture the upscale 27- to 35-year-old audience. Happy couples and happy singles mingle together without regard for normal social boundaries. They’re all holding drinks, but the bartender has lost track of exactly who’s paid. He’s busy serving the newcomers streaming into his large but now standing-room only place.

The television volume is turned off so that the sounds of Blazermania substitute for Sonicsteria. Still, at the end of the first half and the beginning of the second, it becomes clear that the game is being played in Seattle.

“If Bill were out there,” a fan next to me says, “Seattle would be afraid to be intimidating us like this.”

And it’s true that the game, and the entire series, is missing Walton’s fierce presence. Spectators miss him running up the court after each basket twirling his hands over his head in a gesture that reminds the Trailblazers to get back into their set-up and, more importantly, indicates just how excited Walton is.

The fans love Walton not only for his abilities and his whiteness but also because of the obvious joy he gets from playing basketball. His teammates respect him because he makes them all look better. Walton is one of the few superstars who’s more important than he appears. This is why in 1978 his fellow NBA players overwhelmingly voted him Most Valuable Player even though he didn’t lead the league in scoring, rebounding, assists or blocked shots.

In a way it’s fitting that so active a presence on the court should be so passive off it. All of Walton’s friends that I’ve talked with confirm this paradox. They say that he can’t stand losing even a choose-up soccer or volleyball game after a picnic. Yet he rarely gets upset about anything else. Although he shows his displeasure by withdrawing, usually he withdraws just because he wants to be by himself. When Walton does endure an interview, he’s not terribly articulate. With discourse, unlike with basketball, Walton doesn’t get enough practice. Everyone works overtime reacting for him. In the bar watching tonight’s game, for example, many people are talking about “what Bill’s probably feeling.”

With less than one minute left, and his Trailblazers trailing 90 to 102, Coach Ramsay gravely walks over to Seattle’s bench to congratulate their coach. He’s conceding this game, though not conceding that it’s only a game. After the final buzzer, a Portland player says: “To me, this is like a death in the family.”

Of course, in some families, it’s like a rebirth. Jack Ramsay’s wife, for example, so dislikes the attention given basketball that she spends much of the season living in New Jersey. To many a husband plugged into games, his wife may as well be in New Jersey.

Yet in Oregon the Trailblazers have been incredibly tonic for community feelings. As they say goodbye to each other in the bar, these Portlanders already seem nostalgic for a fan’s excuse to relate to friends, acquaintances and total strangers. Everyone here knows not only that basketball is just a game but that spectating is a game as well. Spectators agree to let one another act like chauvinistic fools. Even though you realize that the referees are trying to be fair, you have a right to scream abuse at them. You can—indeed should—wear your enthusiasms all over your body. And for two hours lose yourself in a simple win-lose game whose purpose is to have no other import or point.

Still, the saddest aspect of losing a professional championship is realizing how similar it is to winning one. Life in the San Francisco Bay area was hardly altered after the Oakland A’s won back-to-back-to-back World Series, the Warriors triumphed and the Raiders finally emerged on top of the body heap they call the NFL. Your players end up being traded at the end of the season because of salary disputes and negotiations over exposure in better commercial markets. Or they’re so injured and exhausted after the elongated playoffs that next year they don’t even resemble the horses you screamed your lungs out for. Or, just as likely, you move and are surprised by how fickle your loyalties can be. Finally you realize that a winning home team means little more than the chance to see exciting games more often and live.

Try telling this to the fans in Washington, D.C. After being humiliated in two previous final playoffs, the Capitol Bullets this year beat Seattle to become World Champions. Two days after they won, the Bullets were feted by the White House, As Jimmy Carter tried to palm a basketball, the surrounding Bullets outgrinned him. The wire services sent the photo of this victory scene to newspapers all over the country.

That same day, the NBA held its draft of graduating college players. Beneath the photo of Jimmy, local newspapers speculated on how these new additions might make their teams into White House contenders next year. Hot-dog sporting events were becoming so expensive and nutritionless that spectators could no longer be given a minute to digest. God forbid they might realize how poorly served they were.

Thus local sportswriters began, in effect, to write commercials stimulating demand. Was X, graduating from Minnesota, or perhaps young Z, likely to be another Walton? New heroes were being groomed in case the white superstar didn’t heal. The 1979 basketball season had already begun.