Photo: Todd Tankersley

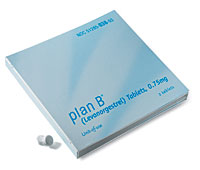

In late 2002, women’s groups sounded an alarm over the appointment of Dr. W. David Hager and two other physicians—all opponents of abortion—to the FDA’s Reproductive Health Drugs Advisory Committee. Although this move involved only 3 of the 11 seats on the advisory panel, advocates from these groups were concerned that these new members would hamper women’s access to birth control. And indeed, this year Hager has played a little-noticed but central role in stopping the over-the-counter (OTC) sale of the morning-after pill known as Plan B.

Hager, a Kentucky-based obstetrician-gynecologist, says that he is being miscast as “some kind of powerful individual” and complains that, with a couple of exceptions, journalists have “never interviewed me before they’ve written about me.” He’s referring to a spate of stories citing his opposition to the so-called “abortion drug” RU486, his attack on the birth control pill for promoting promiscuity, and a book in which he advises Bible readings to relieve premenstrual syndrome. While his critics say these activities show that he is bringing a religious bias to scientific decisions on new drugs, he disagrees. “I make diagnoses based on evidence-based medicine,” he says, noting that “83 percent of patients in this country say that they prefer that their physicians pray with them or counsel them” according to their religious beliefs. “Your faith is an integral part of your life and everything that you do,” he adds.

But last December, at a hearing of his FDA panel, held jointly with the FDA’s Nonprescription Drugs Advisory Committee, Hager didn’t mention “faith” as the panels considered whether to allow Plan B to be sold over the counter. He didn’t dispute that Plan B, a form of emergency contraception, dramatically reduces the

risk of pregnancy when used shortly after intercourse. It generally prevents pregnancy by blocking fertilization, though it can also inhibit implantation of a fertilized egg. Emergency contraception prevented more than 100,000 pregnancies and 51,000 abortions in the year 2000, when Plan B was only available by prescription. In a country where half of all pregnancies are unintentional—more

than 3 million each year—broader access to Plan B could have a substantial effect.

Hager admits that he personally doesn’t prescribe the drug on moral grounds, because he fears it may interfere with implantation. At the hearing, however, he made a different argument, introducing doubts about whether the pill had been adequately tested among adolescents. While another physician on the panel called Plan B “the safest product that we have seen brought before us,” Hager repeatedly questioned whether the research sample of adolescents—29 subjects between the ages of 14 and 16 out of 585 women—was sufficient.

The committees recommended allowing the pill to be sold without a prescription in a 23-4 vote, with Hager in the minority. But in May the FDA took the unusual step of disregarding that guidance, as well as the advice of its own staff, and refused to let Plan B be sold over the counter. In the rejection letter, Dr. Steven Galson, acting director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, cited Hager’s concern—the “inadequate sampling of younger age groups”—as the key rationale for the decision.

Many in the medical community were stunned by the denial, including no less a luminary than Donald Kennedy, the editor-in-chief of Science magazine and a former FDA commissioner. “Normally I don’t criticize my successors at FDA,” he says, “but I think that was not a good call.” James Trussell, director of Princeton University’s Office of Population Research, who voted in favor of the proposal, adds that the FDA’s concern about the lack of adolescents in the sample is a “political fig leaf” giving the agency scientific cover for a decision made to satisfy religious conservatives. He notes that neither the contraceptive vaginal sponge nor the female condom needed such data to be approved, and that scores of drugs, in addition to contraceptives, didn’t require research targeting specific age groups.

Many scientists also note that the components of Plan B have been in use in birth control pills for decades. Dr. Alastair Wood of Vanderbilt University, who sits on the FDA’s Nonprescription Drugs Advisory Committee and voted for approval, explains, “There’s no evidence that this drug has different side effects in younger girls.”

Hager’s was not the only objecting voice. Religious groups like the Concerned Women for America and conservative members of Congress also weighed in against

allowing OTC sale of Plan B, maintaining that access to the pill might cause young girls to be more promiscuous. Yet Hager was at the forefront of the opposition. In June, the New England Journal of Medicine published a letter from Hager and two colleagues criticizing an editorial that supported sale of Plan B without a prescription. That same month, Hager’s status as a cause célèbre of the Christian right was again evident when four members of Congress—two Democrats, two Republicans—unsuccessfully opposed his reappointment by the Bush administration, citing a religious bias. “I would hope that he is reappointed,” countered David Stevens, executive director of the Christian Medical Association, “because he is a man of science and a man of faith.”

As Hager prepares for his next one-year term, he insists that he is first and foremost a scientist and that his position on Plan B re-flects his objectivity. He agrees there’s no particular reason to think young teens would behave differently with access to the drug, but he says he needs evidence before he can reach that conclusion. “I’m saying,” he explains, “we don’t have that information.”